Lots has been said and written about what makes country music “authentic” — but somehow, most of that conversation has been generated about the women who are not-so-quietly trying to change the industry and its audience.

Mickey Guyton, a Black woman, sang the “Star-Spangled Banner” at this year’s Super Bowl — but she was not only initially identified by NBC as a different Black woman singer performing that day, she continued to see a lack of airtime on country radio afterward. Kacey Musgraves’ album “Star-Crossed” was shut out of the Best Country Album award at the 2022 Grammys after the governing body said it sounded too pop, despite being released on a country label. And then there is the entire rise, fall and rise of the career of The Chicks.

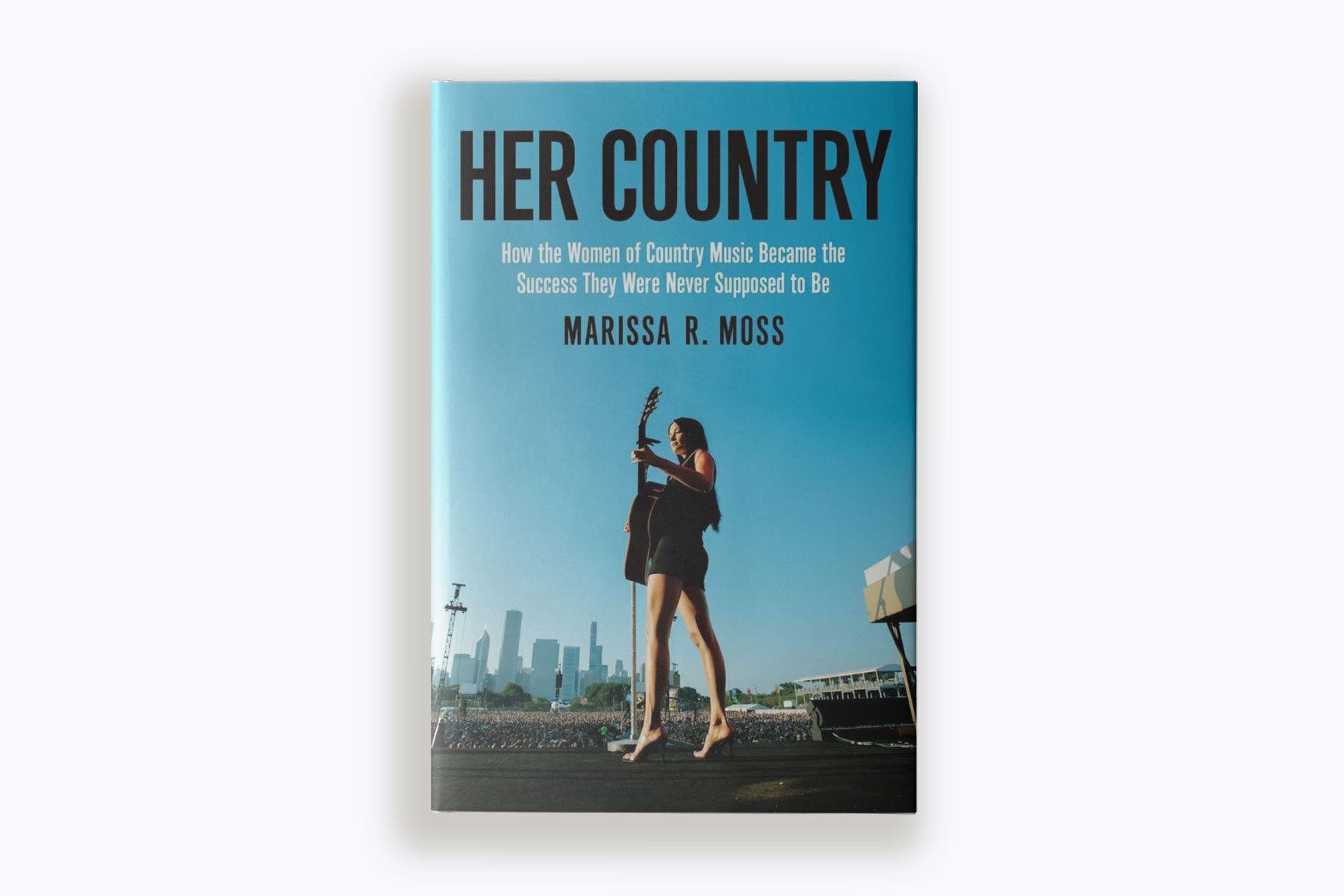

The pushback these women and others have faced throughout their career as a result of their gender and race is the norm, not the exception, of how the country music industry has done business for the past 20 years, says journalist Marissa R. Moss. In her new book, “Her Country: How the Women of Country Music Became the Success They Were Never Supposed to Be,” Moss traces the history of Guyton’s, Musgraves’ and Maren Morris’ career against the larger dynamic that has defined women in country music. They are part of a new class of women artists pushing boundaries to redefine the genre of country music — who makes it, and who listens to it.

The rises of Musgraves, Guyton and Morris — the three artists specifically profiled in the book — is also a story of American politics, Moss argues. It shows how the battle for the soul of country music (and the dollar signs that come with it) mirrors a larger culture war in U.S. politics, as rivaling factions argue over whether America needs to be made “great again” as long-marginalized voices insist on being heard.

“There are these progressive women artists and Black women artists and queer artists and nonbinary artists who are leading this movement in country music, and it mirrors exactly what’s going on in our country right now,” Moss said. “That’s why the book has the title that it does. It’s talking about country music, but also our country that we live in. The book is urging you to see those parallels all at once.”

Moss spoke with The 19th about what it means to think about authenticity, patriotism and equality in the context of race and gender through the lens of country music, and what we might learn about American politics by doing so.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jennifer Gerson: One thing that you touch on a lot in the book is the way that ownership over the idea of authenticity is baked into country music. How do you think this question of who gets to own the idea of authenticity speaks to the future of the genre?

Marissa Moss: Authenticity is one of country music’s most loaded words — you hear it referenced constantly as the measure of what makes something country music. Something I talk about in the book is how it’s convenient that the idea of authenticity can be used to push certain people out of the genre. If you’re not going to play Mickey Guyton on the radio after she played the Super Bowl, the industry is never going to change without some larger fundamental change. In some ways, it’s good to see people splinter off to reach and include the people who should be included in the audience for this music.

Especially when we’re talking about someone like Mickey [Guyton], people will say, “Oh she’s not authentic country.” But what they seem to mean when they say that is, “She’s a Black woman.” Because if you look on paper of what you think would be “authentic” — she’s from the country, she grew up in rural areas, she grew up listening to country music and knows all the greats. Mickey is all of those things on paper, she just happens to be a Black woman.

Your book dives into the question of who gets to decide what country music sounds like. How do you think gender plays a role in this debate?

It’s so interesting what we allow to be called country music and what we don’t. When we’re talking about mainstream country and country radio, we essentially push women and artists of color out. We don’t play them on the radio, they don’t get the top billing on tours and the best sponsorships. Then we use that as a way to say, “Your music doesn’t belong here.” Then when they try to find a new audience — in pop or wherever they can access a better way to get their music to the ears of who needs it — using different production techniques that resonate with a different ear, they are then chastised and penalized and told that they’re leaving behind country music. But country music wouldn’t have them to begin with. It’s this impossible cycle women in country music are stuck in.

The inclusion of a fiddle on a terrible song doesn’t mean it passes this moral test of what’s good. That doesn’t make it country necessarily, and a commercial country song isn’t any more righteous than “Cherry Blossom” on “Star-Crossed.”

We really use this conversation to weaponize women. There are a few bands and artists that are held up as absolute kings of the industry, and they don’t sound like “traditional” country either — but they’re not pop music or influenced by hip-hop. They just sound like a White boy rock band, but they’re not any more “country” than Kacey. It doesn’t mean that I hear the songs being played on country radio and think, “No this doesn’t belong here” — it’s just that those songs are always sung by a man, for the most part.

The book argues country music has long been an integral part of the American political process. Given that we are coming up on midterm elections and the 2024 presidential election, how do you think that country music — and women in country especially — will play into upcoming elections?

I think people forget that Loretta Lynn — in addition to advocating for birth control — was also a supporter of a woman’s right to choose. In her memoir, she explicitly said that while abortion wouldn’t be her personal choice, she thought it was extremely important for women, especially women in poverty, to have access to abortion and control over their own bodies. Somehow, that would be considered divisive now by a mainstream country music star.

I think it’s personally inspiring to see women in country music be vocal. The country music fan can be —though isn’t always — more conservative, or hold strong religious values, so there’s always a lot more on the table to lose.

There are so many people who love country music, but country music has a way of reaching a very certain demographic of people who are very valuable to reach in politics. The people who are being targeted by so many of the policies that are dominating the news right now are people in Texas, people in Florida — the states making headlines are places with a lot of country fans. It is more powerful for country artists to become involved politically now more than ever.

You can have Taylor Swift and Lady Gaga personally co-sign on the Democratic nominee and that wouldn’t be enough to get people to the polls. There are no amount of liberal pop stars that are going to help sway an election. But there are certainly people in rural Texas that their favorite country artists they hear on the radio say something? Yeah, that could help.

The women you profile specifically — Kacey, Maren and Mickey — play with their idea of patriotism in their work and in their public persona, how lyrically and on stage they are forcing the question of what “American values” are. What might country music be doing to change long-held, default assumptions about these words?

Country music’s shift to patriotic mode after 9/11 was really profound and detrimental for women getting played on the radio for many reasons. Your dream was always supposed to be to get back to your small town. There’s this ridiculous thing that happens in country music where you have a guy who has six houses and a private jet standing up there singing about how if only we could all get back to life that centered around high school football on Friday nights.

Then you have Kacey come out with “Merry Go ‘Round” as her first song [in 2012] (The song opens with the lyrics, “If you ain’t got two kids by 21 / You’re probably gonna die alone / At least that’s what tradition told you”), and in the context of a country music scene where you were supposed to love everything about your country and your small town and not be critical at all times of those things.

Nostalgia is a big part of country music, and then Kacey came out and immediately — with her very first single — was critical of that. She chose that to be her very first song, and it was revolutionary in a way. It pissed a lot of people off immediately, that flip of unwavering allegiance to small towns and hometowns on its head. It felt so brave, challenging the way it means to be an American, and an American who loves country music.

[Mickey Guyton’s] “All American” is such an important song. It toys with this idea of being a patriotic country song and it really rips it open a little bit and reclaims it. That is so significant to me, to take this kind of very fundamental country music trope of the patriotic song and then own it for an audience who has never felt themselves represented in those kinds of songs in those kinds of ways, whose own American experiences have never been defined as being “patriotic.”

Mickey Guyton has a very different path than either Kacey or Maren, and, as your book points out, this is unquestionably because of her race. What does the path forward look like right now for women of color in country music?

It’s so insidious how people talk about Mickey’s success. People try to judge her success and her impact that are not comfortable with her being here, and they use the same metrics of success as are applied to everyone else and that’s not fair because she’s not given the same tools. The same doors are not open to her. But her profile is only growing. She’s a commercial country artist and she’s not getting play on the radio. She’s having to change the entire mold.

But with Mickey, the amount of people that see her onstage and feel like they can finally find themselves in country music is so meaningful. There is this domino effect that she’s put into place that’s so meaningful and lasting. I think it will have waves throughout country music — I just hope she gets to experience them herself too, and not just as an agent of change but as someone who wants to be in the space as a commercial country artist. The same things that are available to Carrie Underwood should all be available to Mickey, and that’s obviously not the case.

There are so many wonderful things going on that inspire me daily. Like the Black Opry, this touring collective of Black country artists. Like Rissi Palmer, and Color Me Country radio. Like what Mickey is doing.

I go back and forth between feeling extremely inspired and excited about the future of country, and then feeling dead-assed depressed about it. I guess that’s the way it might be for a while until the big institutions are ready to play some ball.

But what I see happening right now gives me a lot of hope for both our country and our country music.