Marianne Burke can pinpoint the moment she knew Democrat Terry McAuliffe was in danger of losing the Virginia gubernatorial race to Republican Glenn Youngkin.

It was late September, and McAuliffe and Youngkin were facing off in a final televised debate, discussing school curricula and library books related to race, gender identity and sexuality in Loudoun and Fairfax counties, where clashes over what students are learning and COVID-19 protocols made national headlines.

“We must demand that they include parents in this dialogue,” Youngkin said, adding that school systems were “refusing to engage with parents.”

“I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach,” McAuliffe countered.

When Burke and her husband relocated from South Carolina to the Washington, D.C., area, they, like many other families, chose Fairfax County, Virginia, for its award-winning school system. Even though their three children graduated in 2010 and 2013, Burke, now in her 60s, started going to school board meetings again several years ago, amping up her attendance over the past year to show support. She knew how McAuliffe’s statement would sound to some of the angry parents she’d met there.

“We were watching the debate and I said to my husband: ‘This is it. He better explain what he means,’” Burke, a Democrat, said in a recent interview.

Burke said she knew what McAuliffe meant. The message it sent, though, was that “parents weren’t important, that these high and mighty people think they knew better than parents, so therefore parents need to butt out and let the government take care of things,” she said.

-

More from The 19th

- 2022 elections are important, women say — but a poll suggests they may be too overwhelmed to prioritize politics

- House progressives urge Biden to support caregiving workforce and execute other Build Back Better priorities

- Minneapolis teacher strike is part of a wider labor struggle for educators around the country

Youngkin cut an ad centered on McAuliffe’s statement. McAuliffe said in a response that Youngkin was “taking my words out of context.” McAuliffe closed out his campaign at a rally with American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten, at a time when 20 to 35 percent of Democrats believed unions had made it more difficult to reopen schools, according to Education Next polling.

It was a good year for Republicans in a state that has two Democrats in the Senate and last backed a Republican for president in 2004. McAuliffe ended up losing to Youngkin by two points after leading opinion polls for most of the race, just one year after President Joe Biden beat Donald Trump there by 10 points. Republican Winsome Sears won the lieutenant governor’s race by 1.5 points, becoming the first Black woman elected to a statewide office.

“I knew that it was going to make it, at least, very close, and I’m not surprised that he lost,” Burke said.

Republicans believe they can replicate Youngkin’s success in November’s midterm elections by promoting the GOP as the party of parents’ rights — and that it’s a message they will tailor to both energize the base and try to win over independent or politically ambivalent parents who are exhausted by pandemic-related school disruptions and learning delays.

Virginia was one of just a couple states that held off-year elections in November for statewide positions, so its governor and lieutenant governor races were closely watched. Political strategists consider it a possible preview of the 2022 midterm elections, when all 435 House of Representatives seats are up, along with roughly a third of the Senate, and 36 states and territories will be picking governors.

It’s always difficult to compare electorates between a presidential year and an off-cycle year because turnout varies so dramatically: Overall turnout in Virginia was 20 percent higher in 2020 than in 2021. Virginia’s suburbs swung in Youngkin’s favor as compared with Trump in 2020, and Youngkin also did better with White voters, particularly those without college degrees and women.

There was also a “silver surge” among voters older than 65 that one analyst wrote “fundamentally undermines the conventional wisdom that COVID-19 protocols in schools and fears about Critical Race Theory in curriculum determined the outcome of the election.” (Burke pointed out that you don’t have to have school-age children to be concerned about public education.)

Suburban White women are a coveted voting bloc in American politics — and attempts to woo them almost always center around moms. In the late 1990s, they were called “soccer moms.” During George W. Bush’s administration, it was “security moms” worried about terrorism. “Wal-Mart moms” helped elect President Barack Obama. In 2018, “Panera moms” factored into Democrats retaking the House. This year, Republican strategist Sarah Longwell is calling them “COVID moms,” though she noted that the bloc could more accurately be named “COVID parents.”

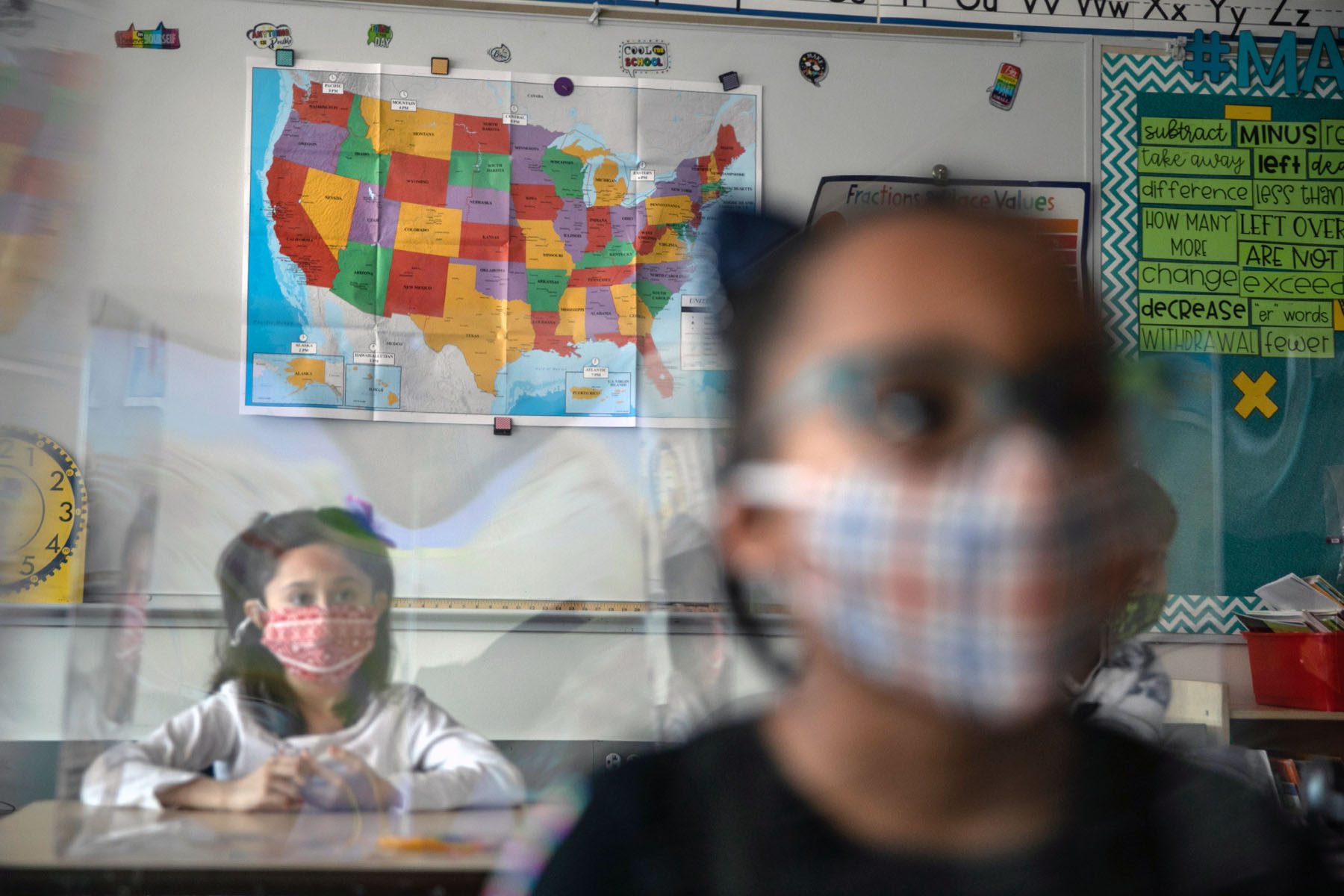

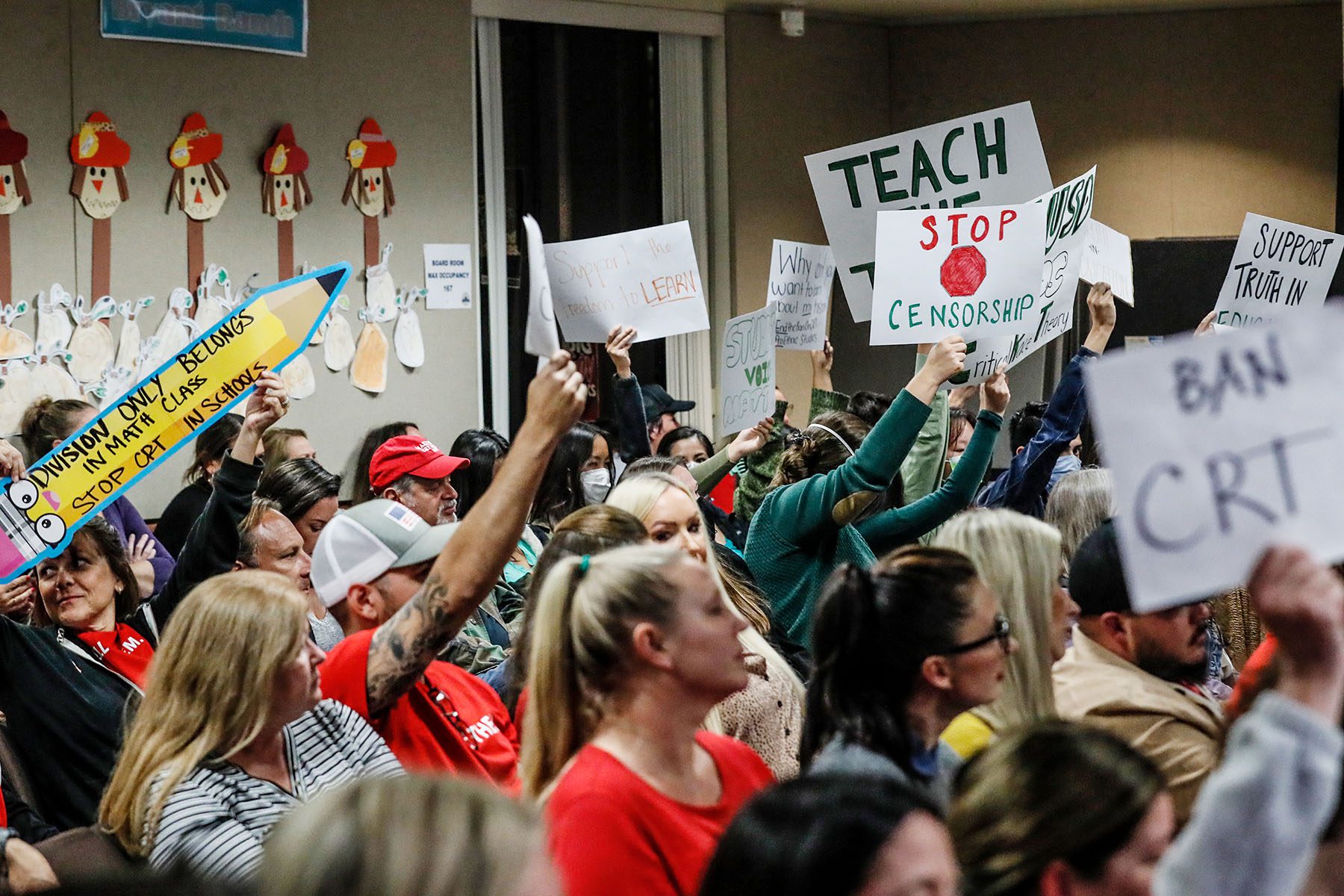

Public schools have long been political battlegrounds. The current iteration of the educational culture wars are state-level Republican bills to restrict transgender students’ ability to play sports; prohibit discussion of sexuality or gender identity in schools (Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill); or ban the teaching of critical race theory (CRT) — a 40-year-old academic framework used for examining institutional racism that is not taught in K-12 schools but became a bogeyman for conservatives after The New York Times Magazine’s “1619 Project” and other efforts to reexamine the country’s racial history.

While these social issues might fire up the GOP base, school districts’ varying responses to COVID-19 — either by closing schools to in-person instruction for periods of time and instituting remote learning, or continuing to require masks after more general state- and city-wide mask mandates are lifted — have created another group of parents feeling voiceless in their children’s education.

Post-Virginia focus groups conducted by the polling firm used by Biden concluded: “School closures + COVID policy were a bigger factor than CRT” but the latter “taps into these voters’ frustrations.”

“Many swing voters knew … that CRT wasn’t taught in Virginia schools. But at the same time, they felt like racial and social justice issues were overtaking math, history, and other things … we should expect this backlash to continue, especially as it plays into another way where parents and communities feel like they are losing control over their schools,” the pollster said. Separate polling released this week by Grinnell College showed that 64 percent of adults believe public schools are on the “wrong track” in terms of what they are teaching. While 69 percent of adults, including 71 percent of White adults, said it was essential to “teach respect for people of different races,” just 49 percent, including 52 percent of White adults, said they trusted schools to teach about racism.

It’s a concern that Republicans have noticed. When Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds delivered the Republican rebuttal to Biden’s State of the Union address last month, she said voters were “tired of politicians who tell parents they should sit down, be silent and let government control their kids’ education and future.” Republican Sen. Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee brought up “parental rights” this week in her opening statement at Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing.

“Republicans at the local, state and federal level are standing with the parents,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky said recently.

“We’re going to keep fighting against these disruptions to family life caused by rules and mandates that are not at all based in science,” he added.

Longwell, the GOP strategist, is in a political universe of Republicans who oppose Trump and works to elect candidates who have spoken out against the former president. One of the things she studies in swing states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Georgia and Arizona is whether “college-educated, suburban voters who didn’t like Trump but were right-leaning in their orientation … are they permanently realigned with Democrats, or were the Democrats renting them for a vote because they hated Donald Trump?” She also conducted post-election focus groups in Virginia to try to answer that question.

Longwell called McAuliffe’s line about how parents did not belong in schools a “fatal mistake.” “I would say a fair number of these people are not hyper partisan about this, they’re just deeply frustrated … and when you’re really frustrated, you want to throw out the people who are in charge,” she said.

Though elected school board officials are the obvious first step — voters in uber liberal San Francisco recalled three in part over pandemic management — political strategists expect COVID-19 education disruptions to factor in other city races like for mayor, as well as statewide gubernatorial elections, for statehouse seats, and even in U.S. congressional races, despite them having limited impact on local schools.

A president’s party typically loses congressional seats in midterm elections, and Democrats are trying to hold onto their slim House majority and their control of the evenly split Senate. With much of Biden’s domestic agenda stalled, including a $1.8 trillion economic package aimed at helping working women, they will need a message that energizes its base to turn out, as well as hold onto some of the crossover voters and independents who backed Biden after souring on Trump. Biden has signaled he believes Democrats can run on a strong economy. Privately, many Democratic strategists worry that the party does not have a midterms message ready for frustrated parents.

“My big picture takeaway is that [Virginia voters] were open — there wasn’t a single one who regretted their vote for Biden. However, there is a deep level of frustration from these voters that I think is going to cause a lot of backsliding in 2022, and cause them to not permanently realign with Democrats, despite the fact that it was on the table,” Longwell said.

Rory Cooper has watched this play out in his Fairfax neighborhood, a place where he said “neighbors who had Biden signs in their yard also had ‘open the schools’ signs in their yard.” Cooper is a political strategist who has worked for a GOP House majority leader and now considers himself a “reluctant Republican.”

Cooper’s three kids are in the Fairfax schools in 6th, 3rd and 1st grades. The youngest is “halfway through 1st grade and he’s never in his life had a normal school day,” Cooper told The 19th in late February. March 1 was the first time he could “go to school and spend an entire day without a mask on. I’ve watched him experience kindergarten on a laptop. He had a teacher who did the best she could and she was great, but it’s hard to watch,” he added.

At first, Fairfax parents did what they could to juggle remote school with working from home. The “inflection point, where even the parents who were being patient said ‘no, forget this,’” Cooper said, was in February 2021, when Virginia prioritized the vaccination of teachers but unions still opposed returning to in-person learning. Many parents mobilized. Cooper started watching school board meetings and spoke at a couple. They were “able to push them to a hybrid model in late spring of 2021” that consisted of no school on Mondays, with two days in person, and two days virtual, he said. Fairfax returned to a normal schedule in fall 2021.

The parents who wanted to reopen schools formed the Fairfax County Parents Association. Cooper described the permanent parental lobbying organization as a “violently nonpartisan” one that stays out of the curriculum debates.

“When you get between a mama bear and her cubs, it doesn’t matter what their partisan inclinations are. All politics end up personal, and this was the most personal thing in their lives,” Cooper added.

Liesl Hickey is a mother and cofounder of N2 America, which advocates for center-right policies affecting the suburbs. The organization rolled out an ad campaign about school reopenings last year, and another about masking in schools last month. Hickey said she predicts parents will remember the after-effects of remote learning — potential mental health issues, cognitive delays — in November congressional races in places including suburban Atlanta, Denver, Detroit and even Southern California.

“The thing about this issue is it is cutting across ideological lines,” Hickey said. “I think that these parents are going to fuel a Republican tsunami.”

The midterm elections are still eight months away. In February, Democratic governors in California and New Jersey — where Gavin Newsom survived an October recall election and Phil Murphy eked out a narrow win in November, respectively — announced they would lift statewide mask mandates, jumping ahead of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance. Other governors quickly followed as opinion polling showed “fatigue and frustration” among voters who believed COVID-19 had become endemic and said it was time to return to some version of normal, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In Longwell’s recent focus groups, concerns such as inflation and Ukraine are top of mind for voters, and she said the best-case scenario for Democrats is that by November, voters see COVID-19 as being under control, schools are open, and families are vacationing. Maybe then, she said, Democrats can “stanch what is otherwise shaping up to be a blowout.” But, she cautioned, “when it comes to schools specifically, to parents with kids … the disruption in education is causing lasting problems … so as long as people are grappling with the consequences of this, it’s likely to show up in voting behavior.”

The past two years have left Angie Schmidt, a married mother of two in Cleveland, Ohio, feeling politically unmoored. Schmidt, who writes about transportation and urban planning issues, said she was previously an “apologist for the Democratic Party” — the kind who would canvass or donate money to get candidates across the finish line. But now she and some of her progressive friends feel “totally demoralized.” She wrote about her experience for The Atlantic.

In the Cleveland Metropolitan School District, which is 64 percent Black and where 42 percent of children live below the poverty line, school board members are appointed, not elected, and meetings are “not set up in a way that’s empowering to parents,” Schmidt said. She got long COVID-19. Her child’s online kindergarten last year often had only a couple of students participating. She estimates she lost about six months of income during the 2020-2021 school year, when she was juggling working with her now 1st grader and preschooler at home. There were just five days of school in January. “It’s just for about a month-and-a-half now I’ve been able to work regularly,” she said in mid March.

Schmidt said she watched as teachers’ unions “dug in their heels” and felt like parents “didn’t have a similar organizing entity.” She cites Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, as the “only person who stuck out their neck” to urge Cleveland to reopen its classrooms.

Schmidt says throughout the pandemic, mothers were expected to be an “unpaid, contingent, essential workforce.” She often felt “toxicity” and “sexism” coming from her own side of the political aisle when she spoke up about reopening schools. “It’s not just the leaders, it’s some of the [Democratic] base … I think there was this habit, throughout the pandemic, of refusing empathy for being impacted by the restrictions, anything short of death was not worth acknowledging,” she said.

While Schmidt still agrees with Democrats on “almost everything … I read the ‘1619 Project,’ and I liked it, I do feel a bit more aligned with independents on certain things now,” she said. “I’m fatigued of the partisan, acrimonious, grudge match and I feel like [Democrats] have gotten a little out of touch with ordinary people’s concerns.”

“This has really taken the wind out of my [political] sails. I’m still healing from this,” she added.