I spent much of this week watching Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearing, which will likely result in her becoming the first Black woman and the sixth woman overall to join the Supreme Court in the institution’s 232-year existence.

But I also started the week thinking about a time before any woman had served on the high court — 1977, specifically, when Congress funded the first and ultimately only National Women’s Conference, designed to address that and other glaring omissions from American democracy.

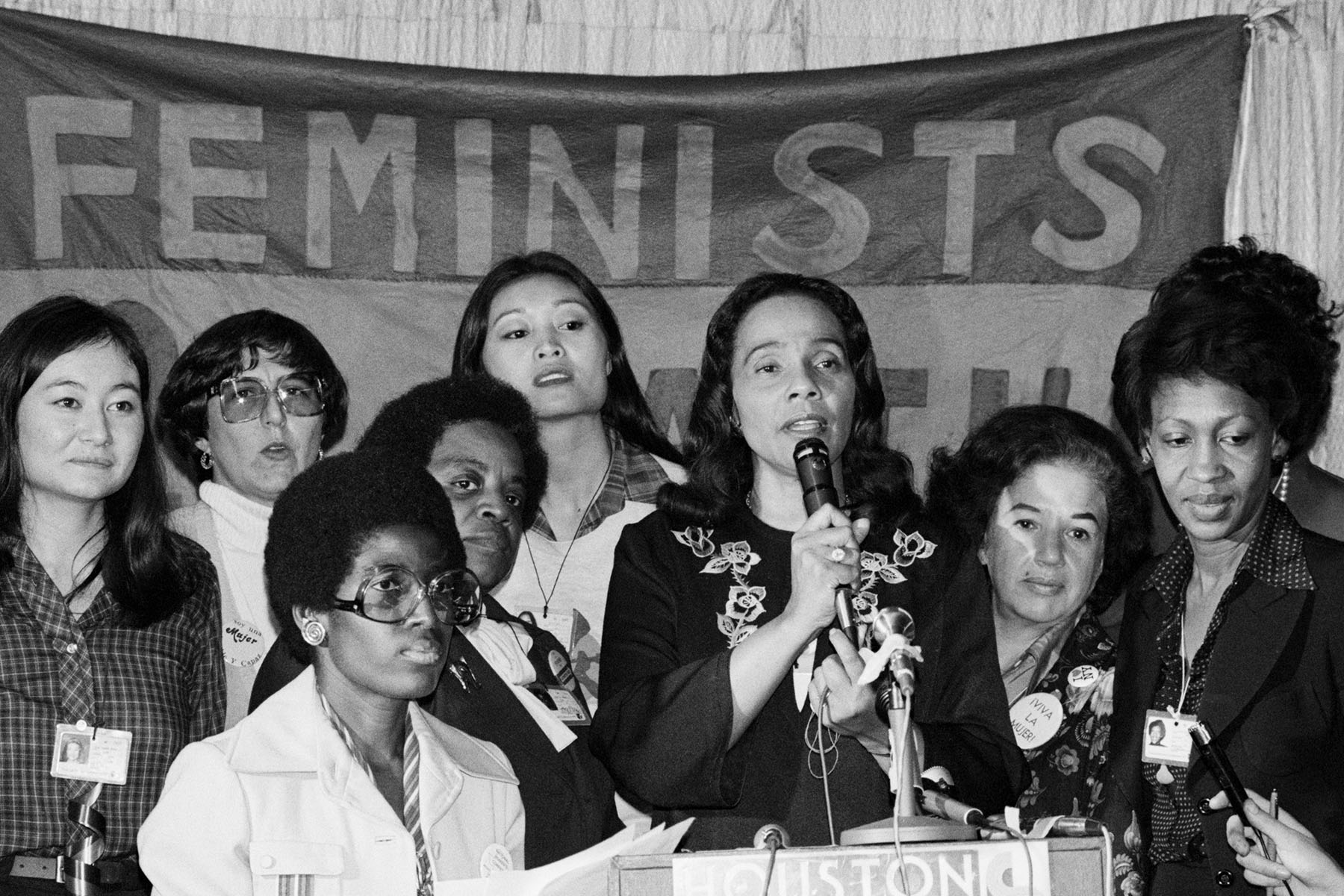

The gathering brought together luminaries including Gloria Steinem (who turns 88 today), Coretta Scott King, Maya Angelou, first ladies Rosalynn Carter and Lady Bird Johnson, and trailblazing lawmakers including Barbara Jordan and Shirley Chisholm, alongside 2,000 women delegates from states and territories across the country. For four days, they discussed and debated issues of gender inequality, in areas such as media, health care, incarceration, poverty, arts and humanities, and elected office. They issued a report, titled “The Spirit of Houston,” submitted to the White House, which outlined their policies and priorities.

Many in attendance recall the conference as empowering and transformative. But despite being covered by hundreds of journalists from around the world, it has largely faded from public memory. Now the University of Houston, and some of those who were there in 1977 or who are studying it, are trying to make sure it’s not forgotten. On Tuesday, with history looming in Washington, I helped kick off the 45th anniversary year of this watershed moment in the city where it began.

Then, Rep. Barbara Jordan of Texas, the keynote speaker of the conference, posited that it was “perhaps the most important conference of women to be held in our country in the past 129 years,” adding, “What occurs here — and what doesn’t occur here — can make a difference in our personal and collective lives.”

As I reflect on the conference, I am at once in awe that such a thing could happen and angered that so many of us — me included — didn’t know about it. (Though the show “Mrs. America” alerted a new group of Americans to its existence.) Where would our country be on gender inequity if more Americans did know this story— if our government and institutions had implemented the recommendations set forth in the conference report?

“We are here to move history forward.” These are the opening words of the Declaration of American Women, written for the original conference, and it was an unprecedented gathering, notes Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, a professor of Asian American studies at the University of California-Irvine who was also my fellow panelist this week and is researching the Asian American and Pacific Islander women who participated in the 1977 convening.

“There’s never been anything like it before or after,” she said. “It’s the only time the federal government gave money and authorized a national committee to develop a women’s agenda. Just think about that … It gave legitimacy for women to talk about issues and to say there were concerns that needed to be addressed.”

But the conference was also remarkable in its grassroots approach, Wu points out. Women delegates were elected from 50 states and six territories, and there was a diversity mandate that a third of delegates be women of color.

The women in attendance brought a diverse range of lived experiences, geography, race, class, sexual identity and ideology — which led to some difficult conversations. Still, the group emerged with a list of policy prescriptions around nearly 30 issues.

“The agenda that was passed paid attention to intersectionality,” Wu said. “They didn’t just default to White, middle-class women,” a problem of the feminist movement of the 1970s, and also of the suffragist movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The goals outlined in the legislation approving the conference don’t seem controversial — from “recognizing the contribution of women to the development of our country,” to “assessing the progress that has been made to date by both the private and public sectors in promoting equality between men and women in all aspects of life in the United States,” and “identifying the barriers that prevent women from participating fully and equally in all aspects of national life and developing recommendations for means by which some barriers can be removed.” Yet the bill barely became law, with a compromise that included less funding that advocates had wanted: $5 million, or less than a nickel for each woman in the country.

The idea of such a convening in today’s hyperpartisan political climate feels even more daunting, said Betsy Fischer Martin, executive director of the Women and Politics Institute at American University and another fellow panelist this week.

“When I was thinking back through everything that came out of the conference, the thought, ‘Isn’t this quaint?’ came to my mind immediately,” she said.

“It was the age of antenna television and record players,” Fischer Martin continued. “The notion of convening 2,000 elected delegates from across the country and ideological spectrum to come together and put forward a set of ideas and proposals struck me as very difficult — and never mind the federal government paying for it.”

We discussed how a gathering around shared concerns about gender equality, regardless of party, far removed from politics or the confines of Washington, could be a way to break through the partisan divide — particularly for the majority of the population and the electorate.

“In many ways, these kinds of things should be top of mind,” said Fischer Martin, who spent more than two decades as the executive producer of “Meet the Press” in the Tim Russert era, when ideological differences were less likely to be inextricable from personal animosity.

“We should be encouraging people to come together, in more formalized settings, to put forth ideas, instead of shouting various thoughts over the airwaves or social media,” she continued. Caregiving and equal pay, helping address inequities that hurt women, shouldn’t be partisan issues, she said. “Solutions have some ideology wrapped around them, but if you can work together on how they happen, that’s how the sausage is made in Washington.”

Sylvia Garcia was a 20-year-old law student when she attended the conference as a delegate from Texas. She was among many women who were hoping the gathering would help build support for the Equal Rights Amendment, first proposed in 1923 by suffragist Alice Paul at the first Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls.

Now one of the state’s first Latina congresswomen after being elected in 2018, Garcia is still fighting for passage of the ERA — her role a sign of both the progress and the work left undone in the generations since the Houston gathering.

“The ERA was so important then, and it brought so many women across this nation as we organized,” Garcia told the audience at this week’s panel. “Regretfully, we still haven’t gotten it done. It’s amazing to me that I was fighting that fight back in ’77 and here I am, as a member of Congress sitting on the Judiciary Committee and we had a hearing on the same thing again.”

The National Women’s Conference was referred to as “Seneca Falls South.” In their post-conference report, organizers put forth an agenda for governments and institutions to adopt — a National Plan of Action. It didn’t have a price tag. It was not possible, they said, to estimate the cost to make all of the recommendations a reality. Some, like leveling the playing field, increasing the number of women in leadership or putting women on the Supreme Court, had no financial cost.

“Whether or not in the long run these would involve spending more money or only a reordering of present priorities for spending depends on decisions about the kind of society we wish to live in,” the report read. “Throughout history, women have been underestimated, undervalued, underpromoted, and underpaid. We do not ask the price of justice. We should not ask the price of equality.”

A lack of action at the national level on much of the conference’s agenda didn’t necessarily signal the event was unsuccessful, Wu said.

“People got mobilized and connected with each other and were really inspired,” said Wu, who added that many women attendees took the policy recommendations back to their local communities and tried to sustain the energy of the conference.

“Patriarchy and racism are still with us, and that’s not the fault of these activists,” Wu continued. “People are invested in the existing power structure, but the National Women’s Conference was this moment that may not have completely transformed things, but leaves a basis of people being excited, interested and wanting to make change.”

The 50th anniversary of the conference comes a year after the country’s semiquincentennial in 2026, and organizers are hopeful that the moment presents an opportunity to revisit the “Spirit of Houston” to consider not only what might have been, but what still can be with an even more inclusive, expansive effort to perfect the union.

“Some of these planks are still good today,” Garcia said. “We haven’t gotten it all done. We’ve made a lot of progress, but we haven’t come far enough and we have much work to do.”

In her keynote, Jordan cautioned against inaction and emphasized the urgency of the moment.

“If we now do nothing positive, constructive and healing, we will have wasted more than money; we will have negated an opportunity to make a difference,” Jordan told the cheering audience at the convention.

“Not making a difference is a cost we cannot afford,” she warned. “The cause for equal and human rights for women will reap what is sown in Houston, Texas, November 18 through 21, 1977.”

Some opportunities to make a difference have been lost, at least so far. Jackson’s nomination is a clear sign of progress — an overdue one. Women still earn less and are still underrepresented at the highest levels of our government and businesses. A woman has never been president. The country has evolved on issues of LGBTQ+ rights even as some of that progress is under threat.

Could women and LGBTQ+ Americans, with an assist from male allies, come together today to try to address these challenges? It’s something that feels both daunting and urgent, an impossible task as our democracy seems intractably divided and partisan concerns continue to stubbornly outweigh gender. The way forward could lie in the lessons of the Spirit of Houston.