Vice President Kamala Harris started her week in Selma, Alabama, marking the 57th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, a seminal battle of the civil rights movement and the catalyst for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Days later, Harris made stops in Poland and Romania in a show of American support for Ukraine as the Eastern European country continues to defend itself against attacks from Russia.

It was a week bookended by threats to democracy, both at home and abroad. Standing at that intersection is Harris, who entered the vice presidency with little foreign policy experience but has taken on the role of diplomat and spokesperson for the United States in multiple high-profile situations. She opened her speech Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge with a link between the fights for freedom, saying of Ukrainians, “Their bravery is a reminder that freedom and democracy can never be taken for granted by any of us.”

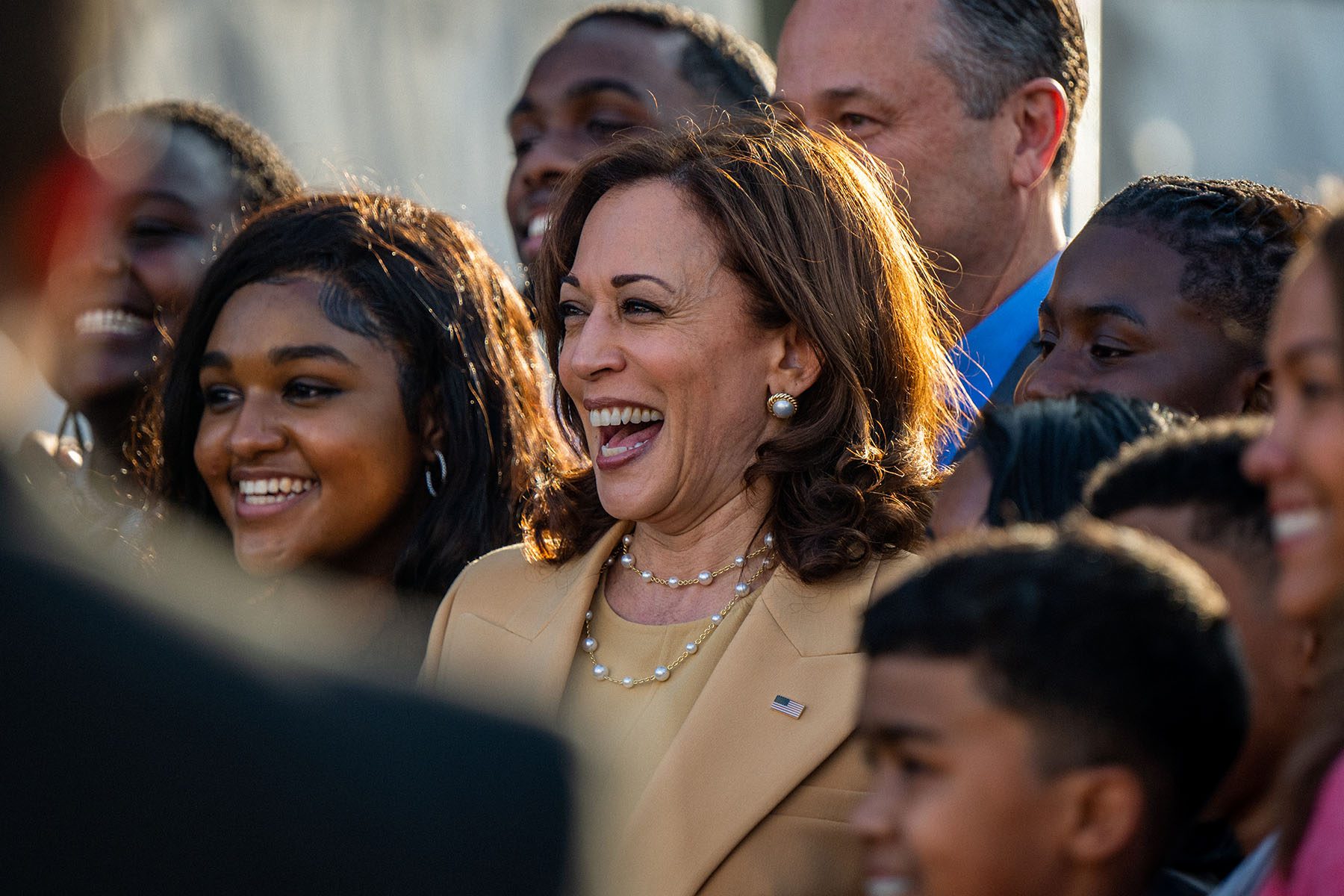

I was struck that she was speaking to a crowd that included the foot soldiers who were beaten and bloodied in that same spot, establishment members of the movement and younger activists who are new to the fight. Harris herself was a bridge in that moment, connecting the need to be vigilant about protecting democracy for people who are literally worlds apart.

-

More from The 19th

- Four Black women became classmates, roommates and lifelong sisters. One of them is now a historic nominee for the Supreme Court.

- Moving in with other adults has become a lifeline for single moms hit ‘tenfold’ by the pandemic

- The only all-Black women’s unit sent to Europe during WWII is awarded a Congressional medal

It’s in many ways unremarkable that an American leader is pushing for democracy and freedom — and in many ways remarkable that the leader doing it is a Black woman. It’s something she’s continually done abroad, for example pressing gender equality and ballot access in remarks to the UN Generation Equality Forum in June and calling for a commitment to freedom in the Indo-Pacific region during a trip to Singapore in August. And while she has done it domestically, too, reiterating the need for federal action on voter protection in opening the president’s global democracy summit in December, activists are worried that not enough is getting accomplished at home.

What does it mean for the second most powerful person in the United States, and the first woman and Black American vice president, to be the standard bearer for the country’s founding principle, in a moment when the future of democracy hangs in the balance? I wanted to ask some of the people in the best position to know, who know the vice president, the office, and the stakes she faces.

‘Going to Selma is a contact sport’

Before Harris took the podium at the base of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, she met with marchers who were there in 1965 as well as current-day voting rights activists. Among them was Melanie Campbell, convener of the Black Women’s Roundtable, who has attended the Bloody Sunday commemoration for years and has also been talking to Harris throughout her tenure on issues of civil rights.

During their meeting, Campbell said she urged Harris to continue to shine a light on the impact of voter suppression and said she hoped the Justice Department — which operates independently of the White House — will extensively use its monitoring program to protect voters.

“She wanted to hear from us, she reiterated her commitment to keep pushing. … She wanted to do follow-up,” Campbell said, adding that the work of her organization and others has been relentless in the wake of backlash to record Black voter turnout in 2020.

That Harris showed up in Selma in a year where she isn’t on the ticket, when Democrats are on the ropes with voting rights legislation stalled in Congress, felt important to Campbell as a tangible way to say the administration wasn’t casting the issue aside.

“Going to Selma is a contact sport,” Campbell said. “It’s not just about what she said, but she met with the foot soldiers. … She’s really leaning in. I think Selma was part of that, people needed to see that. She’s getting out of the White House.”

Democrats and the administration last summer failed to pass meaningful voting reform, including a bill named for former Rep. John Lewis. Campbell acknowledged the defeat is a significant setback for organizers tasked with mobilizing voters headed into this fall’s midterm elections.

“We haven’t had a chance to take a breath,” she said. “We can’t out organize everything, but we have to find ways to win. We have to keep fighting until we win the next battle.”

In many ways, Harris is the embodiment of the marchers’ efforts. A historic first, she was born a year before the Voting Rights Act was passed; her parents were activists who took her to protests in a stroller. In her remarks, Harris referenced her last trip to Selma, which was also the late Lewis’ last time on the bridge where decades earlier he nearly lost his life fighting for the right to vote.

Selma is always a beginning point in terms of democracy, Donna Brazile told me. A veteran Democratic strategist who worked on several presidential campaigns, including civil rights icon Jesse Jackson’s 1984 bid, and a former Democratic National Committee chair, she has been both an insider and outsider in national politics for most of her adult life and regularly talks to people in the Biden White House.

“It was Selma that gave every American the freedom to vote,” she said. “It was an important moment because, had it not been for those who bravely crossed that bridge, there would be no Kamala Harris. There’s a direct connection between our freedom in the United States and the freedom of others. That is what the march was about: the struggle for human and voting rights, which is vital to the success of any democracy.”

Brazile said she was glad to see Harris in Selma making the case for democracy, and that she is also “the right choice” as part of the U.S. military aid and diplomacy efforts as the future of the Western alliance faces a crucial test.

“Her voice and messaging is profoundly important, given what’s at stake,” Brazile said. “She’s tying it all together.”

‘She’s in the fight’

Ashley Etienne is a fellow at Georgetown University’s Institute of Politics (I’m a fall 2020 alum), but most recently she served as Harris’ communications director, and was often in the room as the administration set and carried out its agenda in the first year.

To be a woman and person of color is to come from oppressed groups that have long had to fight for and to maintain the right to vote. In one of Harris’ first meetings, Etienne recalled, the vice president staked out democracy as among the issues she wanted to take the lead on in the administration.

“She believes it’s the one right that unlocks all the other rights, it’s the one that’s the most fundamental,” said Etienne, who also worked in President Barack Obama’s administration and was the first woman and person of color to serve as communications director for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. “It’s about having a voice and influence over your fate in life. We have had to struggle for it in ways that unlocked freedoms for everyone. That responsibility and understanding of the potential of a healthy democracy for all people … she’s a direct representation of that.”

To be at once second-in-command to the leader of the free world and a Black woman means her very presence ties together the relationship between Ukrainians’ determination to be independent and the long battle for civil rights in a country that declared liberty and justice for all. Harris’ particular leadership style, which has been frequently remarked on by her aides and others I have talked to who know her, is to take her seat at the table and look not at who else is there, but at who is missing.

It is an ethos she often takes abroad, as she did this week in a roundtable discussion with Ukrainian refugees. They were a proxy, she said, for the many who had left their home country. “The people at this table represent well over a million people. You are not alone,” she said. “People around the world are watching.”

What they are witnessing, from Selma to Ukraine, is both the value and limits of Harris’ power. As vice president, she is using her bully pulpit, but how that translates into policy or consequences is unclear.

Some of the obstacles to achieving the goals, however, are clear: There is no current path to federal voting rights legislation in Congress. What will happen with Ukraine is also unknown. These threats to freedom are not the same: one is a war and an invasion by a foreign power, the other a more insidious chipping away at the rights of American citizens. But both are key to the administration’s legacy — and, potentially, to Harris’ presumed political future.

How and whether she, with Biden and other allies, can balance the business of democracy and diplomacy to help protect freedom for millions will be a test. It’s a test for American ideals, a test that started well before Lewis and others marched. It is one that is now being faced by a new generation of leaders, including Harris, who has benefitted from democracy’s promise and now must be one of its chief defenders.