When winter storm Uri hit Houston last February, widespread power outages resulted in residents going days without heat and electricity. Almost half of Texans lost access to clean drinking water.

In the neighborhood of Pleasantville, that meant families needed bottled water – and lots of it.

“Because we are in an older community, a lot of people, including myself, experienced pipe damage,” said Bridgette Murray, a community advocate. “Some folks had to turn off water in their homes.”

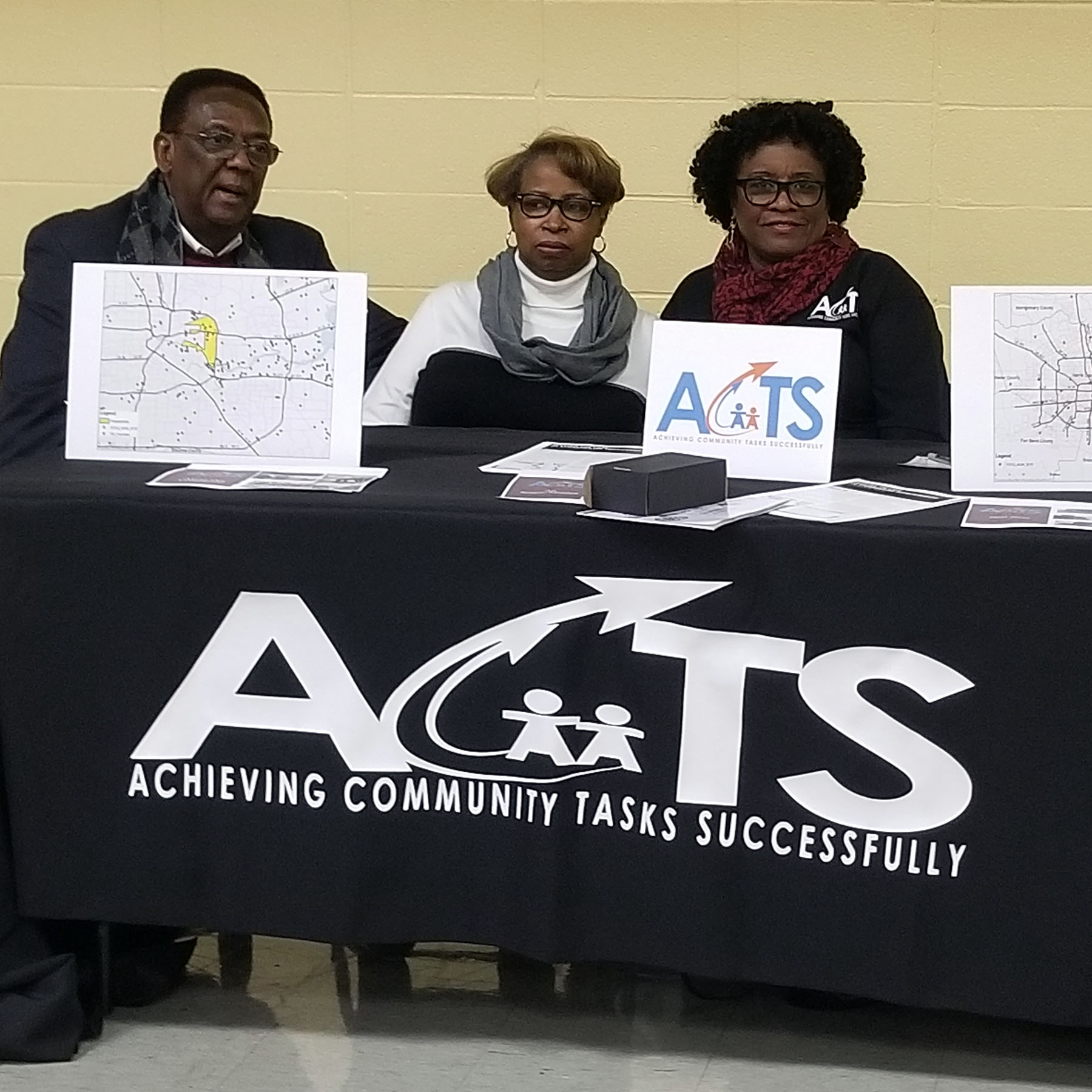

Murray’s organization, Achieving Community Tasks Successfully (ACTS), purchased a truckload of water to distribute in her neighborhood and surrounding communities in the days after the storm.

Pleasantville, where Murray lives, has a long and proud history of community organizing. In the 1950s it was one of the few places where Black Americans were allowed to purchase homes in the city. Like many other communities of color, it also became the place where policymakers allowed the permitting of a disproportionate amount of industrial uses, including chemical storage facilities.

In an effort to understand how those acts of environmental racism impact the health of residents, ACTS facilitated a community-led air monitoring program over the last three years to measure the amount of dangerous pollutants in the neighborhood.

The work that Murray does is directly related to climate justice — a critical component of addressing the disproportionate impacts climate change has on communities of color. But it can be hard for organizations like hers to secure grant funding through traditional foundations. In recent years, some organizations are making pledges to fund this on-the-ground climate work, specifically centering groups led by women of color.

In a report released in 2021 by Green 2.0, a nonprofit that tracks diversity in the environmental movement, foundations that responded to the report funded White-led environmental organizations at nearly double the rate of those led by people of color. And, in an analysis completed by The New School, of the $1.34 billion dollars distributed by national environmental grant makers between 2016-2017, only 1.3 percent was awarded to environmental justice organizations. The disparity is also gendered: Between 70 to 80 percent of philanthropic funding goes to organizations run by men.

In recent years, grant-making organizations like The Solutions Project and The Hive Fund for Climate & Gender Justice are working to direct philanthropy dollars to grassroots work led specifically by women of color. As the climate crisis worsens, and funding for climate action grows, they believe that addressing both gender and climate justice together will strengthen solutions being implemented on the ground by those already in frontline communities.

“Women of color are super underfunded, but are doing so much of this work. Let’s commit to them,” said Sekita Grant, vice president of programs with the Solutions Project.

The work the Solutions Project funds is wide ranging, focused on community-led renewable energy projects, regenerative land work and addressing longstanding environmental injustices like polluted air and contaminated water. Grant said the decision to focus on women’s leadership was made after realizing that, by nature of their positions in their communities, they were already leading many of these grassroots efforts. “(When the) solutions project pivoted, to be more in relationship and collaborative with grassroots organizing, and the climate justice movement,it was a lot of looking around like, ‘Wow, like this is really being led and carried by women of color,’” Grant said.

The reasons for the current funding gap are multifaceted. From the perspective of organizers like Murray, just having access to either grant writers or developing a skill set in grant writing is expensive. The applications themselves are complicated, lengthy and time consuming to complete for both private and federal grants. In an oversight hearing held in February by the the House Committee on Natural Resources on diversity equity and inclusion in grant giving and the environmental movement, Keya Chatterjee, executive director of the US Climate Action Network, provided written testimony describing the process of securing a federal grant as “demoralizing and characterized by a lengthy application process (100 pages long in one instance) with very technical jargon that is difficult to understand.”

On the philanthropy side of things, there is also an inherent bias in what projects, or organizations foundations deem worthy of funding.

“There is a lack of understanding in philanthropy around what change and transformation truly look like,” Grant said. “There is a very narrow sense, in my view that’s recreating the same mess that got us into these problems, where you have this very technical top down approach.”

For these reasons it is also difficult to get funding for advocacy work, said Zelalem Adefris, who works with two Miami-based organizations that received grants from the Solutions Project. Since 1997, one of the nonprofits she works with has sent community members to Tallahassee, Florida’s capital, to advocate for their position on various pieces of legislation. Over the years they were able to cobble together community donations for the bus trips, but it wasn’t until 2020 when they were able to secure a grant for the work. This year they testified in support of the creation of an energy equity task force and against a law that would disincentivize rooftop solar panels.

”When it comes to systems transformation, and the long, hard slog it takes to change policy and to change culture, it is a challenge to get everyone in philanthropy to understand and to support that,” Adefris said.

There are ways to make grant giving more equitable. The Solutions Project — which acts as an intermediary between large grant funders and grassroots organizations — has a simple application process, few reporting requirements and has committed to investing 95 percent of its resources to leaders of color, with at least 80 percent going to organizations led by women.

They also distribute multi-year operational grants, which allows grassroots leaders to be more responsive to the needs in their communities and to plan for growth within their organization.

“Not having to worry about funding as often definitely creates an environment where organizations are able to actually focus on the work and less on keeping the doors open,” said Adriane Alicea, Green 2.0 deputy director.

When Murray received a multi-year grant from the Hive Fund, she was able to secure an office space and is planning to nearly double her small staff. “Generally, grants have to be very targeted to different programs and projects. So it becomes a big assistance to organizations like ours to be able to have some flexibility in how those dollars are used,” Murray said.

But there is a huge disparity in who receives these grants. According to the Green 2.0 transparency report card, on average, organizations led by people of color received less than 1 percent of the multiyear operational budget grants doled out in 2021.

Grant hopes that foundations will come to understand that funding grassroots organizing is central to addressing climate change.

“You’re going to get very rich and high-quality solutions from individuals that are historically, currently, and in the future, committed to that community,” she said. “We can really see the high value and efficacy of this climate justice work.”

Back in Pleasantville, Murray is already working on her next set of grant applications. This year, she hopes to purchase air monitors that can better detect cancer-causing pollutants, which are used by the local government in other parts of the county.

“When you are a smaller organization you are using these low-cost sensors, and that data has to be matched by a regulated monitor so that it can be actionable,” Murray said. “When we are all working from the same type of equipment it strengthens that working relationship [with officials] and gives our program a greater voice.”

Disclosure: The Hive Fund for Climate & Gender Justice has been a financial supporter of The 19th.