The pills used in medication abortions and those often used to treat spontaneous miscarriages are the same — and that has some reproductive health advocates and physicians worried that new laws in many states limiting their use for abortions will have consequences for people who have miscarriages.

People who experience miscarriage can sometimes wait for the fetus to pass out of their body on its own – a process that might take months – or they can seek treatment. Most people opt for treatment, which comes with two options: a surgical procedure performed in a medical office or a medication regimen. The medication method is less invasive than surgery, does not require any anesthetic and can be largely done from home, which can be easier, since the process often takes hours.

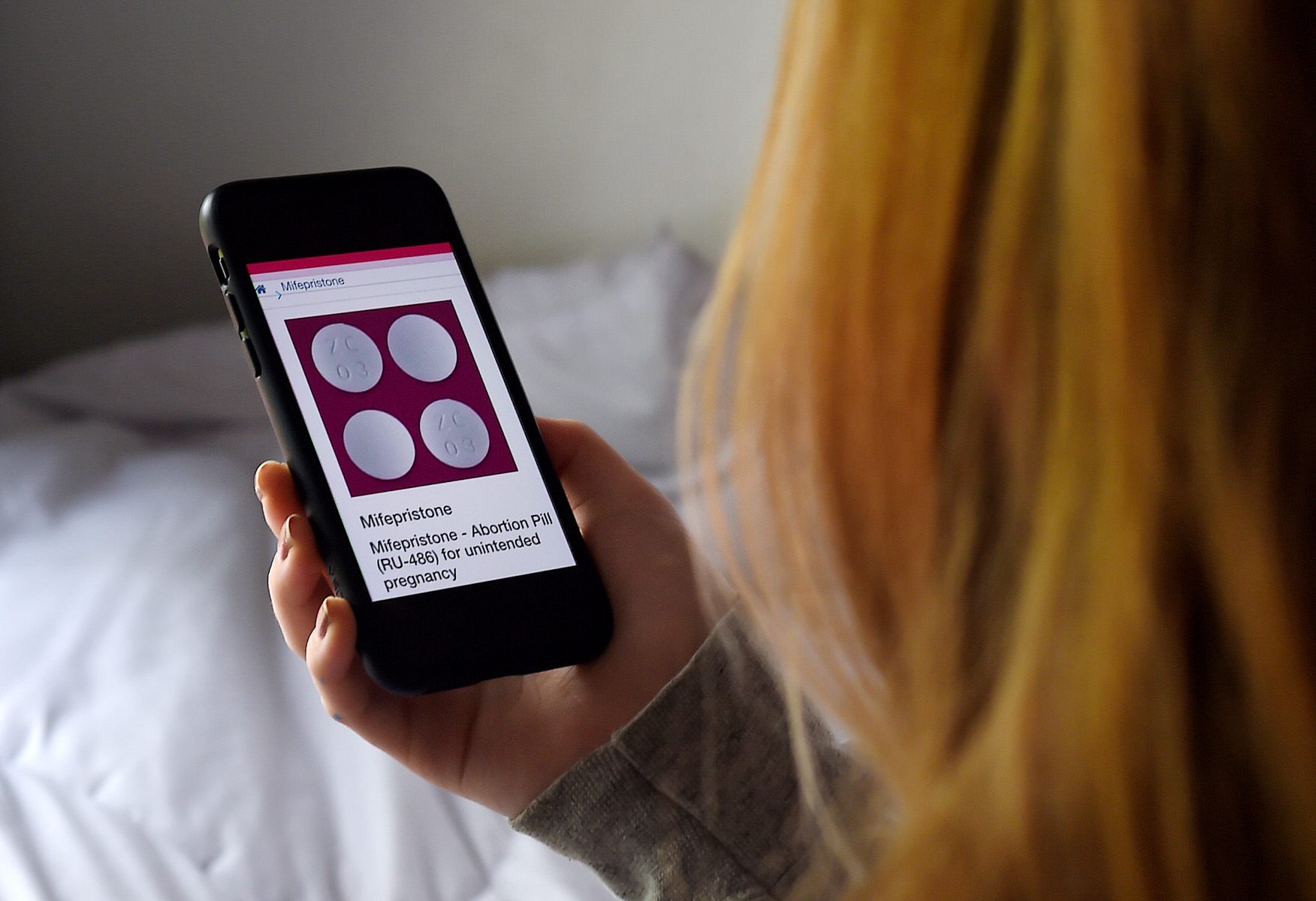

But the medication option — which, under ideal circumstances, involves two pills, known as mifepristone and misoprostol — is essentially the same as the treatment that can be prescribed for people who voluntarily terminate a pregnancy earlier than 10 weeks. That similarity means that laws to restrict access to medication abortion could mean fewer doctors and health care providers who are able and willing to provide those pills for people who miscarry.

“There’s a long-standing history of the intersection of abortion restrictions and pregnancy care in general — and how abortion restrictions confuse, or maybe obfuscate, the care of pregnancy at large,” said Dr. Ghazaleh Moayedi, an OB/GYN who has provided abortions in both Texas and Oklahoma. “We have seen how abortion restrictions, no matter what the restrictions are, impact pregnancy care.”

The impact could be vast. Ten to 20 percent of people who know they are pregnant will experience a miscarriage before 13 weeks, research shows. The true miscarriage rate — including people who did not realize they were pregnant — may be anywhere from one-third to half of all pregnancies.

This year, Republican state lawmakers have indicated that medication abortion is a top priority: Across the country, legislators are preparing and introducing bills that would limit when and how people can access medication abortions. In Texas, medication abortions are prohibited after seven weeks of pregnancy.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court is expected to rule this summer in a case that could overturn or otherwise weaken Roe v. Wade, the case that guaranteed the right to an abortion. If that happens, 19 states have laws on the books that would effectively end access to abortion, including medication abortion.

Advocates and experts note that those laws do not necessarily curb treatment options for people who experience a miscarriage. But many worry that in practice, such legislation could result in fewer health care providers offering medical management for people experiencing a spontaneous pregnancy loss.

Moayedi said there is a potential chilling effect: that, as states pass more restrictions on when and how abortion can be provided, doctors and health care providers in those parts of the country become less likely to treat people with these pills, even in non-abortion contexts. That could be because they are less likely to keep the relevant pills on hand or because they are afraid of being associated with a pill also used for abortions.

That could mean fewer treatment options for people experiencing miscarriage — at least in certain parts of the country. Surgical treatment is an option, but any procedure that involves anesthesia carries risk.

“Anything that happens in the legislatures, in the courts, in the court of public opinion that heightens stigma of abortion, or abortion provision, or increases legal penalties for the provision of care, or simply confounds people about where the legal lines are drawn and whether they can or cannot dispense or provide care — all of that will dissuade people,” said Jill Adams, executive director of If/When/How: Lawyering for Reproductive Justice, which helps people who face criminal charges related to abortion.

Already, that chilling effect has had consequences — in particular, when it comes to the possibility of getting mifepristone. Regulations from the Food & Drug Administration hold that the pill can be prescribed by only health care providers who have signed special agreements with the government, and it can be dispensed by only registered pharmacies.

In practice, Moayedi said, that means the pill is particularly difficult to find at medical facilities that don’t also provide abortions. Federally qualified health centers, which typically serve low-income people and those without health insurance, are particularly unlikely to keep mifepristone in stock — even though they certainly provide care to people experiencing miscarriage.

“Even though we know [mifepristone] improves the chances of successful medical management, it is not routine practice,” she said. “That is because of abortion stigma, abortion regulations and the increased FDA regulations around mifepristone.”

Patients who miscarry do have another option: They can take only misoprostol, without mifepristone. That is more commonly done in many health care settings, because the regulations are fewer.

But misoprostol alone has a 1 in 3 failure rate. Patients for whom the pill does not work would have to go back to the doctor’s office for either another pill or for surgery. All those elongate a process that, for those losing a wanted pregnancy, can be particularly painful.

“People are looking for a quick resolution of the pregnancy, so they can grieve if they need to, and then take the time and return to trying to conceive again,” Moayedi said. “There are huge family impacts, life impacts from these sorts of restrictions, and how they impact all kinds of pregnancy care.”