Prison education programs across the country have long overlooked incarcerated women, offering fewer courses and degree options.

Northwestern University is hoping to change that. Last spring, the university expanded its three-year-old prison education program to include incarcerated women.

At Logan Correctional Center, Shawnette Green greeted the opportunity with enthusiasm. Green, who has been incarcerated at Logan since 2013, participated in the federally-funded Upward Bound education program that allowed her to attend Loyola University Chicago for a summer when she was a child. Now 45, she had always envisioned attending college and was excited to be accepted as part of the first women cohort of Northwestern’s program that began taking classes in March 2021.

“Being from the Chicagoland area, Northwestern was always one of those schools that you just dreamed of,” Green told The 19th in a phone call from Logan Correctional Center. “So immediately when we heard the name and knew that we were going to have the opportunity, we were just really elated and enthusiastic.”

Northwestern’s expansion is part of a broader nationwide push for quality education in correctional centers.

Historically women have comprised a small proportion of the total incarcerated population, which means investments in prison programming tend to focus on men. Women make up about 10 percent of people incarcerated in prisons and jails in the United States, according to government data from 2018. Though the number of incarcerated women is growing at a rate outpacing men, correctional programming for women is lagging.

For example, a 2018 report from the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition found that incarcerated women in Texas had access to an associate degree program and certifications in two occupations: office administration and culinary arts/hospitality management. Men could choose from an associate, associate of applied science, bachelor’s, or master’s degree programs, as well as 21 job certificates.

“I just can’t tell you how many prison education programs I know where they just don’t have any women in their program,” said Jennifer Lackey, a professor of philosophy and director of the Northwestern Prison Education Program. “In our men’s prisons, there have been a lot more challenging high-level educational opportunities for the men than there are for the women.”

For people with longer sentences, those educational opportunities are even more limited, said Erika Ray, 40, who has been incarcerated at Logan since 2010. Those with shorter sentences are typically given priority for classes, she said.

Recently, calls for robust criminal justice reform have prompted more colleges, companies and foundations to invest in degree or certificate programs for incarcerated people. In December 2020, Congress lifted a 26-year ban on Pell Grants for incarcerated students. In 2021, thanks to new grant funding, universities like Northwestern and Washington University in St. Louis developed programs that offer incarcerated women not only quality classes but also courses with credits that they can use toward a degree.

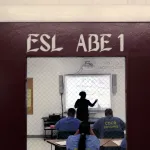

Northwestern’s first women cohort included 20 students taking classes like expository writing, sociology, philosophy and STEM. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, the launch of the program last spring was limited to teaching courses by mail correspondence. That has since expanded to hybrid Zoom and in-person classes. Mary Pattillo, a sociology professor with Northwestern and instructor with the prison education program, said she used the same syllabus and assignments that she does with other Northwestern students. Pattillo noted how the maturity and range of life experiences of the women at Logan Correctional Center adds layers to the classroom discussions that she may not see at Northwestern’s main campus in Evanston, Illinois.

Pattillo’s class was among Green’s favorites; she said she sees a difference in the level of challenge and rigor she gets from the Northwestern program compared with other courses she has taken at Logan. Lackey hopes Northwestern can help lead the way for other schools to broaden educational offerings for incarcerated women, and that it’s important to treat their Northwestern students in prison as they would students in Evanston.

Criminal justice experts have told The 19th that trauma-informed services aimed at rehabilitation, including higher education, can assist with harm reduction while women are incarcerated and lead to better outcomes for them when they are released. About 75 percent of formerly incarcerated people will be rearrested within five years of their release, Lackey said. Prison education can reduce recidivism by 43 percent depending on the level of courses.

Additionally, incarcerated women are more likely than men to report experiencing sexual violence or mental health challenges in their past, experiences that are often linked to committing crimes and entering the criminal legal system. Supporting better education for incarcerated women and beyond is crucial to bridging opportunity gaps and helping people live productively, Green added.

“Having experienced sexual abuse at a young age, it really does change you. It’s like moving your entire identity, and then you don’t really know at what point in life you will come to yourself or rediscover you,” Green said. “I believe overall education is a huge part of creating people who feel more confident in themselves, feel more capable and, therefore, present as a better version of themselves in life.”

“I think that that is one of the powers of education, you feel like you deserve the best of everything when you have people believing in you, but then being able to believe in yourself,” Ray said.