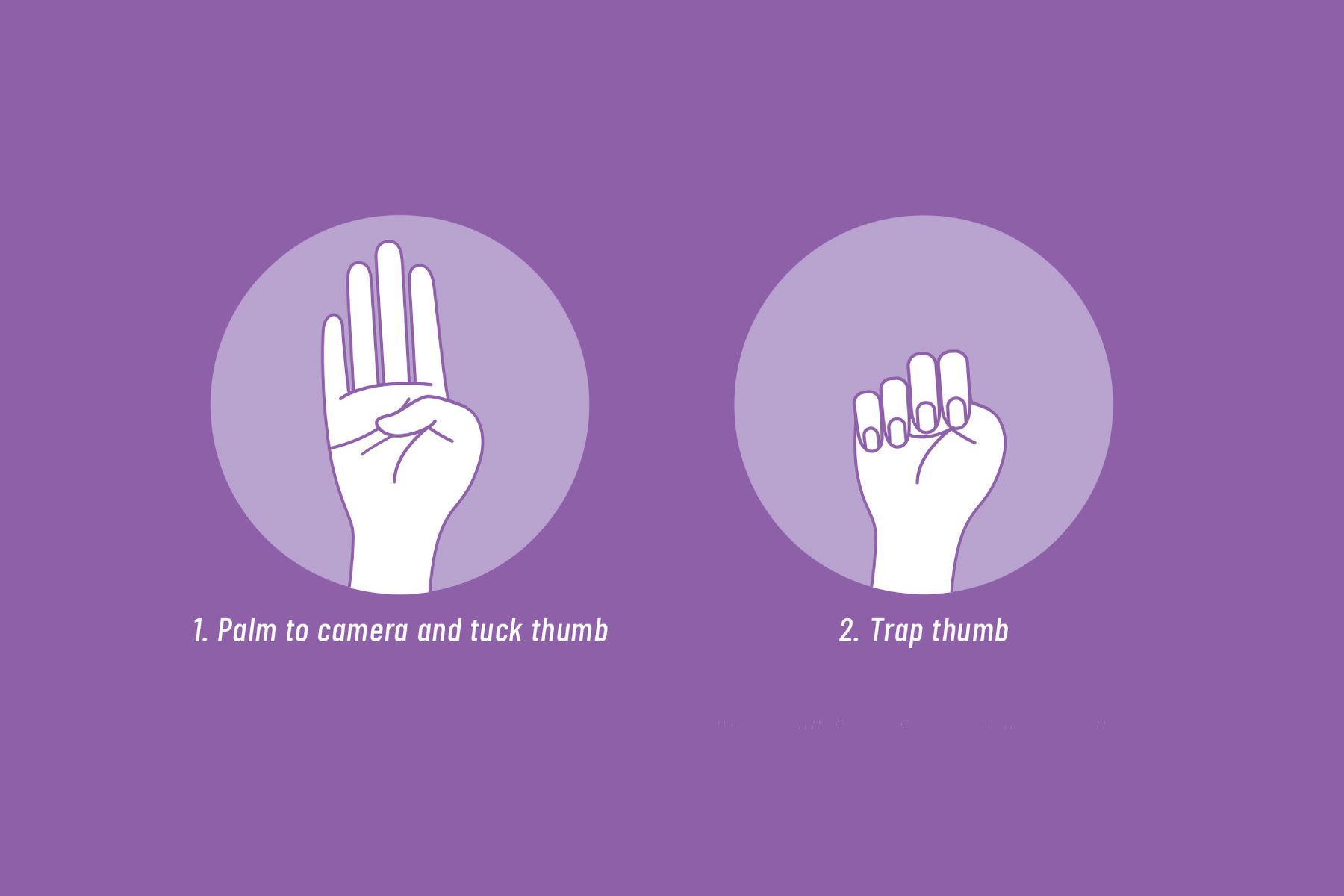

Palm facing outward, other fingers curled around the thumb. This simple gesture — resembling a closed fist — led to the recent rescue of a 16-year-old girl who had been reported missing from North Carolina days before.

The girl sat in the passenger seat of a silver car traveling southbound on a Kentucky interstate and appeared to be “making hand gestures” to other vehicles, officials said. A driver recognized the hand gesture from a viral TikTok video, knew it meant the girl was in danger and immediately called the police. When the silver car exited, officers from the Laurel County Sheriff’s Office were waiting to arrest 61-year-old James Herbert Brick, who was charged with kidnapping, unlawful imprisonment and possession of matter portraying a sexual performance by a minor.

The gesture was created by the Canadian Women’s Foundation in April 2020 as the pandemic left many isolated in their homes. As people had fewer chances to interact with others or be seen, the organization saw a need to find other ways to signal distress. By July 2020, about 1 in 3 people in Canada knew about or had seen the signal used, according to public opinion polls.

“This new reality requires new methods of communication to help those facing gender-based violence,” Paulette Senior, the president and chief executive of the foundation, said in a statement at the time.

Andrea Gunraj, the foundation’s vice president of public engagement, said that she was surprised to see how quickly knowledge of the hand gesture disseminated. In addition to the teenager in Kentucky, Gunraj said she heard a Turkish woman used the signal on her YouTube channel and was assisted by a viewer. Another person reached out to the foundation and said they saw the hand gesture being used on a Zoom call and were able to support a victim of family violence.

“Certainly our hope was that it would spread and be useful,” Gunraj said. “It is a surprise, however, that it was shared on channels we weren’t even on. We didn’t have a TikTok at the time … It’s no surprise to me that social media has become a space for marginalized people to speak about things that they’ve been silenced on in other spaces.”

Maybe it’s a tale as old as time, and now we have TikTok instead.

Hilary Fussell Sisco, a professor and chair of strategic communication at Quinnipiac University

Discreet hand gestures, signs and codes are not new when it comes to women’s safety. For years, people have developed ways to covertly ask for help, from printed flyers to coded language. However, innovations in technology continue to change the landscape.

Hilary Fussell Sisco, a professor and chair of strategic communication at Quinnipiac University, said the role of technology in keeping victims safe should not be overlooked. Sisco pointed to two recent high-profile missing cases in which social media played a role.

“Technology, and social media specifically, are having a major impact on crime as well as public awareness of victim assistance,” Fussell Sisco said. “Between the recent story of the TikTok rescue in Kentucky and the overwhelming social media response to the Gabby Petito case, the public and law enforcement are sharing information widely. If used in the right way, it can be very successful in finding out more information and even helping those in need as these two cases have shown.”

Fussell Sisco said she remembers a time when it was more typical to see hotline numbers on bathroom stall doors to assist people who might need help. Now, there are secret websites, safety apps and social media platform initiatives.

“We found ways to transfer intimate knowledge to people in specific situations,” she said. “Maybe it’s a tale as old as time, and now we have TikTok instead.”

A public service announcement about domestic violence aired during the 2015 Super Bowl, and it featured a former 911 dispatcher who once received a phone call from a woman asking for a pizza. He eventually realized she was actually asking for help. Then in November 2019, a woman in Ohio made headlines when she used the same strategy. Afterwards, a controversial TikTok trend emerged as users posted reenactments of an abuse victim calling 911, pretending to order a pizza and then asking about the specials. In these videos, the operator, recognizing the coded language, contacted the authorities and sent help.

TikTok has also notably played a role in magnifying a missing persons case. When 22-year-old Gabby Petito went missing while on vacation with her fiancé in September, many social media users mobilized to find her, sleuthing for clues online. Many of these amateur detectives used TikTok to post updates, analyses and share the missing notice widely.

Still, the vast majority of missing persons cases and domestic violence incidents go unpublicized — particularly when it comes to Black, Indigenous and transgender women. And the reality is innovations in technology can also be used by abusers and perpetrators, according to experts.

Kris Macomber, an associate professor of sociology at Meredith College, said technology can often be used to further abuse or manipulate people. For example, GPS trackers can be used to stalk or control someone’s whereabouts. Social media accounts can be accessed without consent to monitor interactions.

The rise of dating app usage led to its own challenges as more people began to meet with strangers from the Internet. In 2016, a restaurant in Florida posted a sign in the women’s restroom that read: “Is your Tinder or Plenty of Fish date not who they said they were on their profile?” If yes, then order an “angel shot,” it said, to alert the staff that someone needs help.

Jennifer Pencek, director of the Office for Prevention of Interpersonal Violence at Juniata College, said one consideration is not everyone will understand these codes or beware of the latest signals for help.

“We always encourage bystanders to pay attention to how others are acting and what is happening around them,” Pencek said.

So many violent crimes thrive in silence. It’s good to talk about these issues, think about ways to be active bystanders and really pay attention to the meaning behind what others are saying or doing, Pencek added.

“The hand gestures and viral TikToks show how prevalent this problem is and raises awareness of abuse that isn’t always talked about,” Fussell Sisco said. “Domestic violence and abuse and sexual violence and abuse remains unspoken a lot of the time. But it’s hard to navigate the peaks and valleys of viralness. How deeply will this resonate with people? Next month, what will it be?”

For Gunraj, the hand gesture is just one tool and won’t be the right thing to use for everyone. The next step, she said, is teaching people how to better assist victims of abuse. Next month, the Canadian Women’s Foundation plans to release a guide for people to help them respond appropriately when they see someone asking for help.

“People often say they’re afraid of making things worse,” Gunraj said. “That’s a fair comment, and we need to build up our competencies to be able to speak to these things. Just as the signal went viral real quick, we’re hoping the training around being a great responder to people in need will similarly go viral.”