This project is a collaboration between ELLE.com and The 19th.

Trust Women was flooded with patients; doctors and staff in the Oklahoma City abortion clinic were scrambling to care for everyone they could. It was March 27, 2020, the beginning of the United States’ COVID-19 crisis. Earlier that month, Texas’ governor had announced a temporary ban on elective surgeries — an effort, he said, to conserve medical resources. The ban had included abortions. Almost immediately, Texans seeking care turned to Oklahoma, their neighboring state.

That Friday morning had been particularly hectic. By 10 a.m., the Trust Women clinic had already seen eight patients. And then came the phone call: Julie Burkhart, then the clinic’s CEO, was asked by a local TV reporter for a comment on breaking news — Oklahoma had also temporarily banned abortions as COVID surged.

Burkhart called her attorneys and explained they had procedures in progress “right this minute.” Could they finish the day out and see the rest of the patients? She was advised to finish procedures on anyone who had already been prepped — but then they had to stop.

Burkhart and her sister Christie, then the clinic’s chief compliance officer, turned to Dr. Christie Bourne. They were lucky she was there that day. Bourne, like most of Trust Women’s providers, travels from out of state to perform abortions at the clinic. But unlike most of the 15 physicians the clinic contracted with at the time, Bourne was licensed to practice in both Oklahoma and Kansas, where Trust Women’s other clinic is located.

They had to go to Kansas, now the only state where they could legally care for patients.

The day was a blur. Burkhart stood outside of the Oklahoma City clinic urging patients to follow them to Wichita. She doesn’t remember the 160-mile drive between the clinics, or even whose car she rode in. But she arrived at Trust Women Wichita — nestled between office buildings and a motel — at some point that afternoon. The Burkharts and Dr. Bourne walked into the building, past the security guard and metal detector, and into the clinic’s main waiting room. At the reception, the phones were already ringing with calls from Oklahomans.

Similar pandemic abortion bans were put forth in a handful of conservative-led states, immediately drawing heavy criticism from physicians, who stressed that abortions are more time-sensitive than most medical procedures. Some bans were rescinded or expired; others were blocked by courts. Following legal challenges, both Texas’ and Oklahoma’s abortion bans had lifted by the end of April. But Trust Women felt the impacts acutely. “Immediately, it was like the floodgates opened in Wichita,” Burkhart said.

Clinic employees scrambled to reschedule patients at the Wichita location once Oklahoma’s ban went into effect. Over the next two days, 50 women from Oklahoma and Texas got abortions in Wichita. Trust Women’s four intake coordinators couldn’t handle all the calls; seven new volunteers were trained to help. The clinic upped the number of days they offered patient care from two days a week to six.

From the beginning of March to the end of May that year, 147 patients came from Oklahoma to the Wichita clinic, per Trust Women’s records. Another 203 came from Texas.

It was an explosion. For comparison, in the entire year of 2019, 85 Oklahomans and 25 Kansans got an abortion at any of the four clinics operating in Kansas.

Kansas Republicans repeatedly asked their state governor, Democrat Laura Kelly, if she would instate a ban like those to her south. Kelly refused. The abortion abyss ended at the Kansas border.

The spring of 2020 underscored a reality that has long been clear to those familiar with abortion policy in Kansas: Choices made in neighboring states are felt here. And the state’s own policies have implications that radiate hundreds of miles beyond its borders.

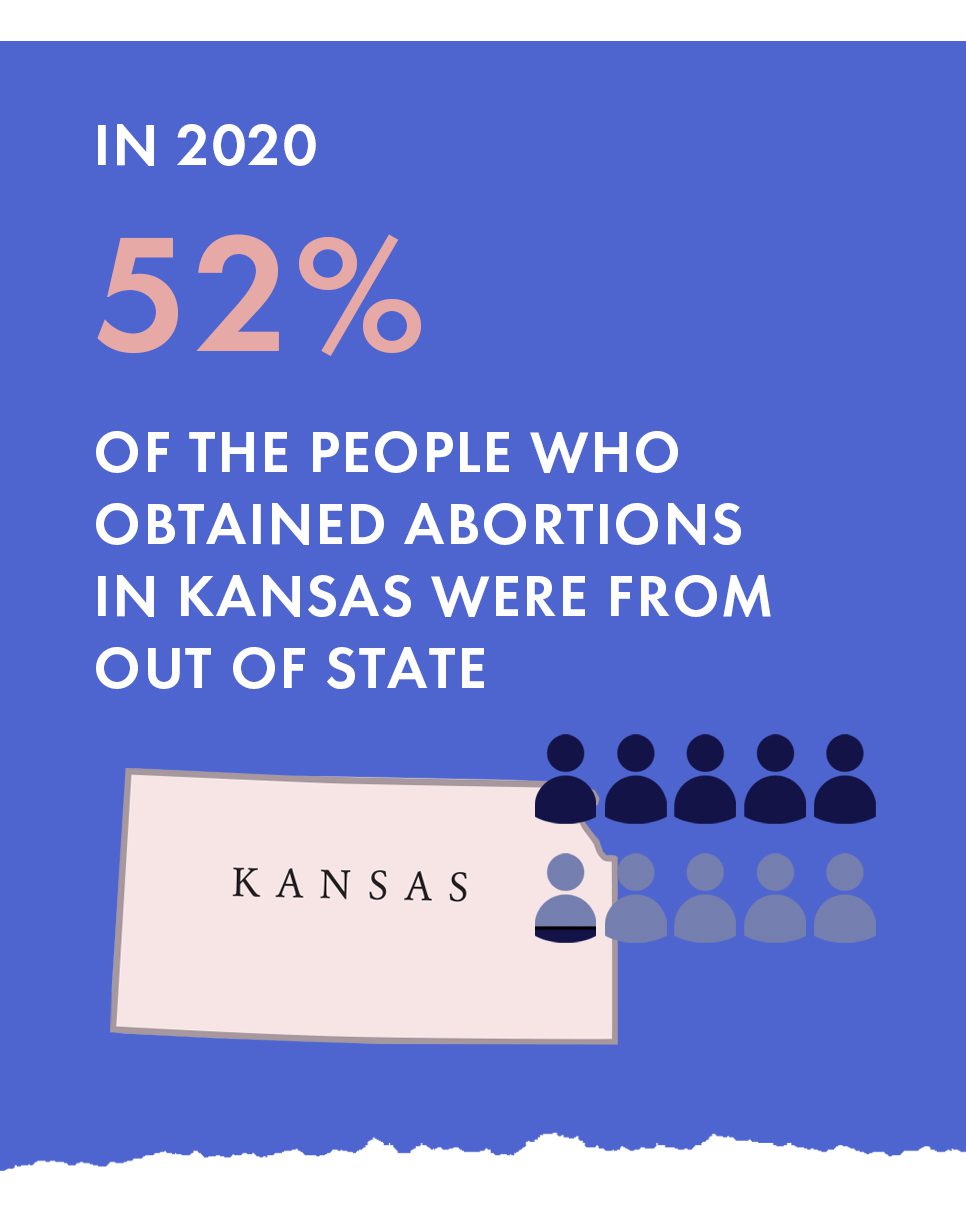

About half of Kansas’ abortions are performed on people from out of state, mostly from neighboring Missouri, which has only one abortion clinic and some of the harshest abortion laws in the country. But as the states circling it continue to tighten abortion restrictions, Kansas has increasingly become the easiest access point in the region.

People from Oklahoma, Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas — which just effectively outlawed abortion by banning the procedure after six weeks of pregnancy — are turning to Kansas for abortion access. For many of the residents of those states, reaching Kansas is easier than heading to New Mexico or Colorado, which also have less stringent abortion laws.

But this may be about to change. In 2022, Kansas voters will decide whether to preserve the right to have an abortion in a statewide election. Kelly, the governor — who is currently a reliable stopgap for blocking anti-abortion measures — is also up for reelection in what national observers say could be one of the country’s toughest statewide races.

In a single year, the elements that have made Kansas a beacon for access could disappear. If they do, the Midwestern abortion desert would be bigger than the entire country of France.

“Kansas really is the center of a lot of it, both nationally and from a regional perspective,” said Brittany Jones, an anti-abortion lobbyist at the Family Policy Alliance of Kansas.

Jones moved to Kansas in 2018 to advocate for enhanced abortion restrictions and to help oust state lawmakers who might stand in the way. So far, that has meant lobbying in Topeka and campaigning to elect anti-abortion candidates. Her work could have outsized impact now, with the anti-abortion constitutional amendment going before Kansas voters. Jones is also working to unseat Kelly in the gubernatorial election. Jones says the Lord called her here to do this work. “I wanted to be a part of what’s happening here,” she said. “As goes Kansas, goes a lot of the Midwest.”

The next year in Kansas will offer a microcosmic view of a debate unfolding across the nation, as lawmakers, advocates and health care organizations begin to envision an America without Roe v. Wade — one where states, not the federal government, decide if and under what circumstances abortion is legal. Three of Kansas’ neighbors — Oklahoma, Arkansas and Missouri — have passed “trigger laws” designed to immediately outlaw abortion if Roe v. Wade is overturned, leaving people seeking abortions to turn to other states. It’s not clear if Kansas will remain an option.

Abortion is currently protected in the state by a 2019 decision from the Kansas Supreme Court, which interpreted that the state constitution guarantees the right to “personal autonomy,” including access to abortion. The ruling, which has stood as an impediment to anti-abortion legislation, blocked a state law that would have banned dilation and evacuation abortions, the most common procedure after 15 weeks.

Kansans will vote next August on whether to maintain that protection or amend their state constitution to remove abortion as a fundamental right. Abortion rights supporters and opponents are planning to spend millions of dollars to mobilize voters around the constitutional amendment, which will be on the state’s primary ballot. It’s the second effort to pass the amendment, which must be approved by two-thirds of the state legislature and a majority of Kansas voters. The first attempt failed in 2020.

Months before that vote, the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to deliver its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, its first major abortion decision since shoring up a conservative majority with Justice Amy Coney Barrett. In its term beginning in October, the court agreed to address the constitutionality of a Mississippi law that would ban the procedure after 15 weeks. The law goes against a core tenet of Roe v. Wade, which guarantees the right to an abortion until the fetus is independently viable, typically around 23 to 25 weeks. Advocates, analysts and observers believe that case could either undo or drastically weaken national abortion protection, allowing for a flood of new prohibitions.

Emboldened by that possibility, Republican legislators across the country have prioritized abortion restrictions, passing laws that likely violate Roe v. Wade in its current state, but could survive if the court scales back federal protections, as many anticipate. In the past year alone, 19 states have passed 106 new abortion restrictions, the most ever since 1973. The majority of those laws have been blocked by lower courts.

Tory Marie Arnberger, the Republican state representative who set in motion the vote on the constitutional amendment in Kansas, said that even if national and state-specific abortion protections are eliminated, she doesn’t believe the legislature would have the votes to pass a total abortion ban. State Democrats argue otherwise. Annie Kuether, a Democratic legislator since the late 1990s, believes the threat of a governor’s veto and an unfriendly state Supreme Court are the only reasons Kansas hasn’t already passed bills that would effectively ban abortions. “Unless we have a very different kind of election and get more moderates and Democrats in the Kansas legislature—and I don’t see that happening—they’ll have the numbers to pass whatever they want,” Kuether said. “They will be giddy with the number of restrictions they can dream up.”

Kuether has observed firsthand Kansas’ shift on abortions, and knows that the barriers the state currently has in place, the ones that keep it from passing the kinds of laws that exist in the states around it, are precarious at best. Before Roe v. Wade, Kansas was one of fewer than 20 states that had legalized abortion in some form. As late as 1989, it was one of the few states that had no restrictions on second- or third-trimester abortions. But just a few years later, things began to turn.

The shift was slow at first, easy to miss. In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court opened the door to state abortion restrictions with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, wherein it ruled states could regulate abortion as long as they didn’t create an “undue” burden for people seeking the procedure.

Almost immediately after the ruling, Kansas Republicans began proposing and passing new limitations on abortion such as waiting periods — first 8 hours, then 24. But the debate was different then. Abortion legislation wasn’t bitterly partisan, and some bills got Democratic support, too. The restrictions legislated were relatively small. And lawmakers were focused on other things.

“We were focusing on things like transportation and financing schools. Abortion wasn’t at the top of the list,” Kuether said. “We were always dealing with abortion back in the ‘90s and early 2000s, but it wasn’t this. It didn’t feel like it was a total, vindictive, ‘Let’s get women’ kind of thing.”

Kansas didn’t become an anti-abortion leader until more than a decade later, in 2011. The political shift was part of a national story. Across the country, Tea Party-backed Republicans swept into state legislatures in the 2010 midterms. In Kansas, moderate Republicans — long the dominant voice in state politics — lost their seats to more conservative party members. The gubernatorial victory of Sam Brownback, who ran pledging tax cuts and abortion restrictions, was hailed by the state’s anti-abortion movement.

Nationally, 2011 was a record-breaking year for new abortion restrictions. Since 1973, never had there been a year with so many new abortion restrictions. (Never, that is, until 2021.) Kansas lawmakers passed 14 new restrictions in 2011, more than any other state that year. “The floodgates opened,” said Elizabeth Nash, a D.C.-based analyst who tracks state policy for the Guttmacher Institute. “It was Kansas, and Oklahoma, and Texas, and Indiana. And it wasn’t like you were seeing a few restrictions. They were totally reshaping what it meant to access abortion care.”

Kansas became an early adopter of many restrictions now prevalent in red-leaning states: They passed the nation’s second ever law to ban abortions after 22 weeks of pregnancy, massive limitations on when private health insurance could pay for an abortion, and strict regulations on where and how second-trimester abortions could be performed. “The whole chamber changed,” Kuether said. Any chance they had to put in an abortion restriction, they took: “It was things like trying to change how many lightbulbs are in the clinic. Anything they could do to anybody running anything to do with abortion.”

Per data compiled by Guttmacher, Kansas passed at least one new abortion restriction a year between 2011 and 2018, with a brief interruption in 2016. The momentum only stopped when Kelly took hold of the governor’s mansion in 2018, part of a national wave of Democratic victories.

-

More from The 19th

- LGBTQ+ seniors fear having to go back in closet for the care they need

- ‘I did feel that the people in the room did believe me’: Anita Hill and Christine Blasey Ford discuss testimony

- Planned Parenthood groups detail the impact of Texas’ abortion law on patients and providers in legal brief

Kelly, who through a spokesperson declined multiple interview requests, has vocally opposed abortion restrictions, and has clashed frequently with the Republican-led statehouse. Advocates on all sides of the debate point to her as a major obstacle to more stringent abortion restrictions, including the six-week abortion bans that have spread throughout conservative-led states since 2019.

Even now, abortion regulations are one of the first policy items the statehouse tackles, said Jan Kessinger, a former Republican legislator who was first elected in 2016. If not for Kelly, he said, the state would have almost certainly become even more restrictive in the past three years. “It became a Republican-Democrat fight,” he said. “This became so partisan, instead of, ‘What’s right for Kansas? What’s right for women? What’s right for medicine?’”

Kessinger is a lifelong Republican. His grandfather and father were state legislators, and he interned for Bob Dole at the Republican National Committee in 1972. When he ran for office in 2016, he was focused on undoing Brownback’s economic policies.

Last year, Kessinger voted against two proposed abortion restrictions. One was a bill Kelly ultimately vetoed, requiring abortion providers to tell patients that medication abortions could be reversed — a claim with little to no scientific basis. Kessinger originally voted to pass the bill, but later refused to join his party in overriding the governor’s veto, helping doom the legislation. His mind changed, he said, after he reviewed the evidence published in medical journals.

The other vote was to block the legislature’s first effort towards an anti-abortion constitutional amendment. Kessinger was one of only five Republicans across the House and Senate to vote against it. Those votes ended his political career; in the 2020 state Republican primary, Kessinger lost by more than 10 points to an opponent endorsed by anti-abortion groups like Kansans for Life and the Family Policy Alliance. Students for Life Action, another anti-abortion group, contacted more than 4,000 people in support of his challenger. (But the conservative efforts to elect an anti-abortion legislator failed: In the November 2020 general election, a Democrat went on to win the seat.)

Kessinger doesn’t view himself as an abortion rights supporter. If anything, he’s uncomfortable with it. He does, however, believe that “legislators make bad physicians” — he would not want the state of Kansas to make a decision on behalf of his daughters or granddaughters.

Three other Republicans who opposed the amendment retired that year. The other dissenter, a state senator, also lost his primary. Outside of Kessinger’s district, Republicans gained seats in both chambers of the statehouse this past cycle. And this year, legislators — worried the pandemic would cut the session short — tackled the abortion amendment almost immediately. This time, every Republican voted in favor. The amendment passed easily. Now it is up to the voters.

Kansas is a safety net, but an unlikely one. Abortion care in Kansas hasn’t felt like a guarantee for over a decade — at least not to the people providing it. The state’s history of abortion access is shrouded in violence and intimidation that culminated in the assassination of one of the United States’ most famous abortion providers.

That trauma is palpable in Kansas’ reproductive health community. It shapes access to this day, limiting the number of doctors who feel safe providing abortions in the area and increasing clinics’ reliance on providers who fly in from out of state. Trust Women is only one of four abortion providers in Kansas. Two are in Overland Park, just half an hour from the Missouri border; the other two are in Wichita.

Even here, in a state that is a refuge, one of the places where abortion rights are guaranteed, it doesn’t feel so easy. The right doesn’t feel safe and protected.

It’s impossible to talk about abortion in Kansas without mentioning Dr. George Tiller. When Tiller’s father died in a 1970 plane crash, he took over the family practice with plans to wind it down. But Tiller didn’t know that his father, a general practitioner, had secretly provided abortions for years before they were legalized.

“He had women coming to him, asking if he was going to help them in the same way his father had helped people — and that was with abortion. Six months turned into a year, turned into five years, which ultimately turned into the rest of his life,” said Burkhart, who worked for almost a decade as a lobbyist for Tiller’s medical practice. “He said at the end of the day, he couldn’t say no.”

Tiller was one of the few physicians who terminated pregnancies in the third trimester, a rare and controversial type of abortion that in Kansas can be performed if there are life-threatening complications to either the fetus or the pregnant person. By 2009, Tiller’s clinic, known as Women’s Health Care Services, was one of maybe three in the entire country that provided them. As a result of that work, he quickly became a bête noire for anti-abortion activists and right-wing media.

By 1975, his clinic had attracted its first protesters. Republican Phill Kline, Kansas’ attorney general from 2003 to 2007, devoted much of his career to investigating Tiller for potential abortion law violations. (Tiller was charged in 2007 for 19 alleged misdemeanors, but was acquitted on all counts in 2009.) Former Fox News commentator Bill O’Reilly referred to him on air as “Tiller the baby killer.” “I can’t tell you what intense pressure we were all under,” Burkhart recalled. “And Dr. Tiller was the person who was most under that pressure.”

In 1986, Tiller’s clinic was firebombed, resulting in more than $70,000 worth of damage. Five years later, in July 1991, thousands of abortion opponents — drawn in particular by Tiller — came from all over the country to protest outside Wichita’s abortion clinics. Protesters set up blockades outside clinics, lying down on sidewalks and in parking lots, screaming at physicians and patients. The bulk of protests lasted through August — what anti-abortion advocates would later dub the “Summer of Mercy” — though some people stayed for a year and a half, said John Carmichael, a current Democratic state lawmaker.

Carmichael and his wife went to the clinics almost every weekend, waking up early to get there before the anti-abortion protesters. On other days, Carmichael and others helped transport doctors to work, rotating drivers and pick-up locations to prevent targeting, with many of the physicians, including Tiller, wearing bulletproof vests.

Even after the protesters left, the violence persisted. Tiller drove an armored car and hired personal security guards. But it wasn’t enough. In 1993, an anti-abortion activist named Shelley Shannon shot Tiller outside the clinic, wounding both his arms. Tiller went to work the next day. But 16 years later, on May 31, 2009, while Tiller was volunteering at his church, he was shot and killed by an anti-abortion activist. He was 67.

Carmichael and his wife planted daylilies that spring, which had blossomed within days of Tiller’s death. He left some on his grave. The flowers are still flourishing in Carmichael’s yard. “I knew Dr. Tiller for 40 years,” Carmichael said, his voice catching. “The man literally gave his life for abortion rights.”

Two weeks after Tiller’s funeral, Burkhart first talked to his widow, Jeanne, about reopening the clinic. The Burkhart sisters had both been close to Tiller for years. He had mentored Julie since she was a college student; he had performed an abortion for Christie when she was a teenager.

But initially, the idea went nowhere. For years, the building stood empty. “There were so many conversations, but people were scared. They were afraid. They were upset,” Burkhart said. “People thought we were going to bring violence back.”

In 2012, Jeanne Tiller sold the clinic to Burkhart, who renamed it Trust Women. Now, the organization lobbies for reproductive health access in addition to operating its two clinics, which provide medical services including abortions, contraception, hormone therapy, and other routine obstetrical and gynecological care. Burkhart headed the organization until this July.

The pain and fear that sprung from Tiller’s death lingers, though. It’s difficult to find doctors in the state — in Wichita, especially — who feel safe performing abortions. Only one full-time provider lives in the city. “People don’t want to live in a hostile environment. They don’t want to put their lives or their loved ones or families at risk,” Burkhart said. And Tiller’s story serves to many as a reminder of that providing an abortion — or seeking one or supporting one — can make them a target.

Today, in Trust Women’s Wichita waiting room, there are bulletin boards with notes from former patients, who write thank yous and words of encouragement. The music is quiet, and there are noise machines and soft armchairs for patients while they wait. Out front, though, anti-abortion protesters set up shop daily.

They try to divert the clinic’s patients toward Choices Medical Clinic, a “crisis pregnancy center,” which are common organizations in the anti-abortion movement. Typically religiously-backed, these are not regulated as medical centers, and instead work to dissuade people from getting abortions, luring them in with promises of free ultrasounds and pregnancy tests. Many of these centers have been criticized by physicians and come under scrutiny for marketing themselves as full-range health care facilities.

Only a fence separates Trust Women from Choices Medical Clinic. A van covered with illustrations of mangled fetuses is permanently parked between the two buildings. “What’s the difference between ISIS violence in the Middle East, and abortion in America?” the truck reads. “Only the victim’s age.”

Harassment and threats are a fact of life for the Trust Women staff. Stormi H., Trust Women’s assistant manager, said that sometimes their neighbors will climb on a ladder, pull out a bullhorn, and yell at Trust Women’s employees over the fence, telling them their paychecks are covered in blood and calling on them to repent. It’s so familiar that Trust Women’s employees know the names of the protesters who yell in their direction. (Stormi, like many of the clinic’s employees, asked that her full name be withheld for safety reasons.)

“My family hates my job for that reason. But my family doesn’t pay my bills,” she said. “I’m going to keep doing it every day, because I do love what I do — I love knowing that I help people.”

Stormi came into this role almost by accident. A friend of hers who worked at Trust Women told her of a job opening, coordinating patient intake. She had no background in reproductive health care, but jumped at the chance. She wanted to offer women a voice of support that she never had.

Thirteen years ago, at age 23, Stormi discovered she was 12 weeks pregnant. Her family told her she had two options: adoption or keeping the child. Abortion wasn’t on the table. “Before I worked here, I didn’t know a damn thing about abortion myself. It was a terrible word. It couldn’t be said in my family,” Stormi said. “When I even mentioned it, I was shunned so bad. That was just a terrible thing. How dare I even think of it?”

She gave birth to a child who is now 12 years old. She loves her daughter, but she still thinks about what could have been — what it would have been like to have her body, and her wishes, respected. Could she have gone to college, like she was planning?

When Stormi speaks with patients, she said, many haven’t told anyone else they are getting an abortion. She is often the first person they discuss their fears and hopes with. “There’s a lot that don’t feel comfortable saying, ‘I don’t want kids.’ We’re kind of ingrained as women to believe that that’s our goal,” she said. “And it doesn’t have to be.”

The August election is still more than a year away and there is little polling examining how Kansas voters feel about maintaining the state’s constitutional abortion protections. State Republicans are tight-lipped about what legislation they would put forth if the state’s constitution no longer guarantees abortion rights. Advocates in the field are bracing for the worst. “We have to win this,” Burkhart said. “I wish we had a crystal ball. But if things do not work our way, it will be that much harder.”

The amendment vote will be part of a primary election that abortion rights advocates fear will favor Republicans. The state GOP will also be voting on a gubernatorial candidate to run against Kelly, but other than the abortion amendment, there’s nothing on the ballot expected to motivate Democratic or unaffiliated voters in the same way.

For now, the signs of the abortion amendment campaign aren’t yet visible. But soon enough, they’ll be everywhere. Advocates are planning for radio spots, TV ads, roadside billboards, and flyers handed out door to door. But even if the state maintains protections for abortion, the bevy of laws restricting access in neighboring states could put Kansas’ already-fragile reproductive health care network to unprecedented tests.

On a Friday morning in late May, Burkhart was struggling through the end of a long week. Originally, she had been scheduled to sit down with The 19th the day prior. But it had been a whirlwind. That Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court had just agreed to hear the Mississippi abortion case. “I’ve been operating in crisis mode,” Burkhart said from her office in Wichita. “What else do you do, with everything going on?”

The Supreme Court was only part of it. To her south, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott had just signed a law banning abortion at six weeks. The ban hadn’t taken effect. That wouldn’t happen until September.

But Burkhart already knew what would happen. Texans seeking an abortion — scared and unsure if the procedure was still legal in their state — would do what they always did every time a new abortion restriction was signed: They’d turn to Wichita. And the phones at Trust Women would start ringing.