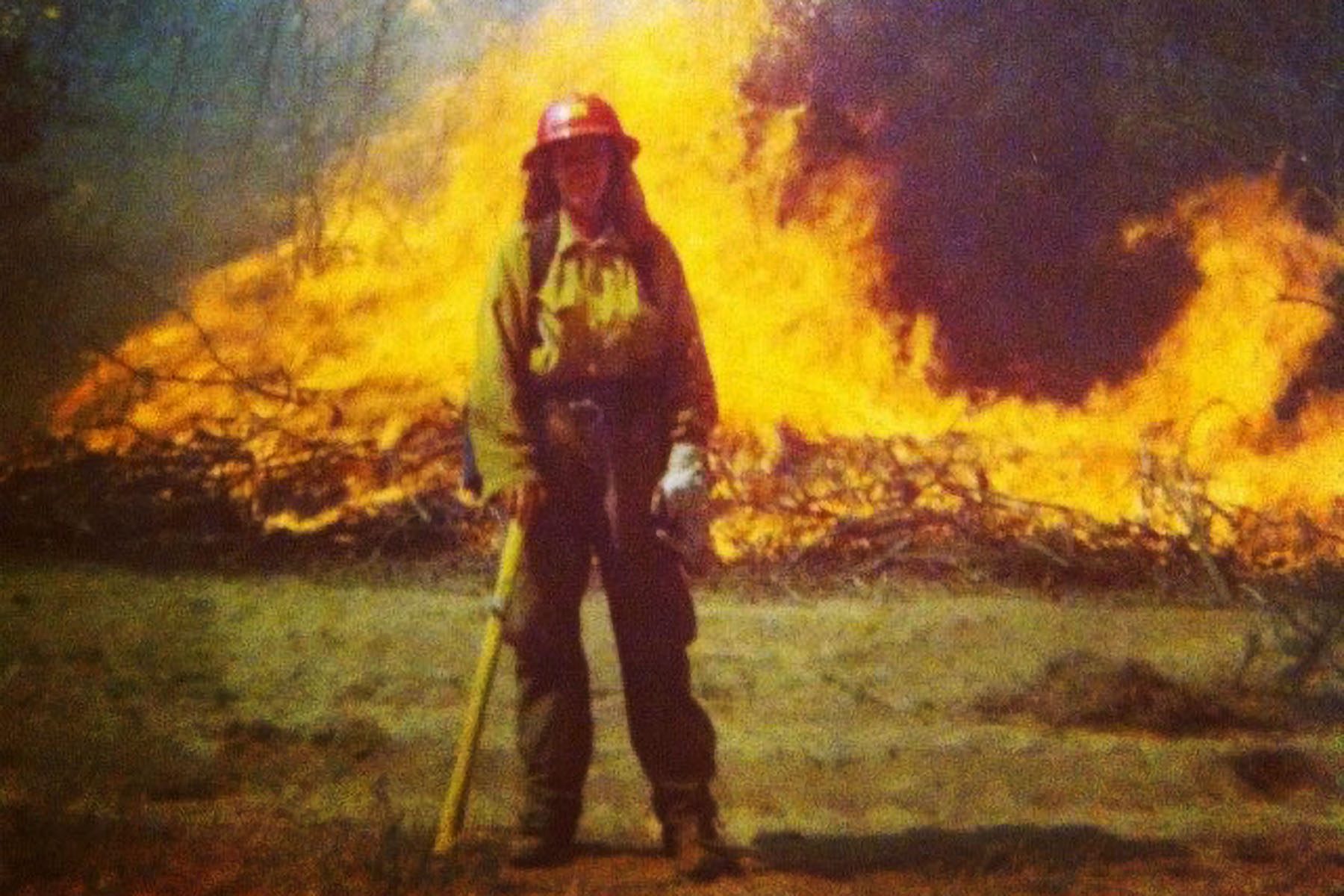

“I am very scared of fire, terrified of fire. But it’s something that draws us in.”

Katy Wolf, 23, just moved to a new town after five years at the Battle Creek fire department in Keystone, South Dakota, where she had kept two weeks’ worth of supplies packed to leave for out-of-state wildfires on as little as three hours’ notice.

Now, 350 miles away in Aberdeen, South Dakota, she’s joined the volunteer firefighter team, taking on fires in a more suburban setting.

Wolf joined firefighting as soon as she was legally able to — celebrating her 18th birthday with a live fire test — and plans to stick with it as long as she can.

“That’s what I love to do, but I can’t do it forever,” she said. She said she was happiest in the field, on the ground, but that the work takes a toll. “Our bodies aren’t going to last forever.”

Only 8 percent of all firefighters in the United States are women, per data published last year by the National Fire Protection Association. And there is little research about what women firefighters experience on the job and what unique risks they face in a male-dominated (and overwhelmingly White) field that exposes them to toxic smoke, typically offers minimal pay and benefits, and is still learning how to accommodate pregnant and injured workers.

These shortcomings matter all the more in a field experiencing persistent personnel shortages as states battle record wildfires in the middle of a pandemic that has put greater pressure on first responders.

The job can demand 72-hour-shifts and lead firefighters to wildfires in the middle of nowhere, to trailer park steps that need to be rebuilt for a patient with limited mobility, or inside an apartment to comfort an abuse victim. And day to day they contend with an uncomfortable truth: The longer you serve, the more likely it is that you will watch someone die.

The ability to cope with these demands rests on trust in one’s crew, but that’s something women firefighters can’t always count on. A 2019 study published by the Center for Fire, Rescue & EMS Health Research (CFREHR) found that 37 precent of women reported verbal harassment and sexual advances on the job — and that those who experienced more discrimination reported a greater number of days when they were physically ill or injured.

What research exists shows that the field has struggled to recruit and retain women, said Brittany Hollerbach, a postdoctoral researcher at CFREHR. Anecdotally, three women firefighters told The 19th the same thing: that they’ve watched many women leave after a year or two.

The 19th spoke with eight current and former female firefighters, plus a nonbinary former firefighter, who have worked in urban, suburban and wildfire settings to learn what they need in their work — and what the dangerous, but rewarding, job means to them.

Amy Hanifan, president of Women In Fire and assistant chief at the McMinnville Fire Department in Oregon, is most worried about data gaps on how firefighting impacts women’s reproductive health and how it could make them more susceptible to cancers, she told The 19th.

“It’s information that women should have access to before they make some decisions about their career paths, their lifestyles,” she said. She and other researchers are trying to alert more women to this information through a FEMA-funded grant made in partnership with Women In Fire.

Three firefighters told The 19th that cancer and reproductive risks were never discussed on their crews. Another woman said she knew about some cancer risks, but not many details. Another said that most of what she knew came from classes with the Firefighter Cancer Support Network. One said the risks were covered in Northwest Florida Fire Academy.

Stacy Selby, a former hotshot, learned a week and a half ago that they have decreased lung function. Hotshot crews are often assigned to tackle the most challenging and hottest parts of wildfires, and often don’t have chances to thoroughly clean themselves or their gear while on long treks.

Selby said long-term health effects of the job were never meaningfully discussed on any of their crews.

A study of Florida firefighters published in 2020 tried to breach a virtual total lack of data on cancer and cisgender women firefighters. Researchers found evidence of increased brain and thyroid cancer risks in women on the job.

A flyer detailing reproductive risks for women — which more men should be aware of as well, Hollerbach said — will debut next week at the Women In Fire conference in Spokane, Washington. Certain chemicals and metals firefighters are exposed to on the job could be absorbed faster during pregnancy. Miscarriage rates among firefighters are 2.3 times higher than the national average, and firefighters as a whole have higher infertility rates.

“A lot of doctors that are in the OBGYN field don’t necessarily have an understanding of what firefighters do from day to day,” Hanifan said.

Hanifan is one of 150 women fire chiefs in the United States, per Women In Fire’s latest count. When she was hired at the McMinnville department, she was the first woman to ever be hired in a full-time position there, she said.

Since she joined the crew, more women have joined the line and pregnancy leave policies have been introduced, she said. To bring similarly positive change, women firefighters also need zero-tolerance policies for harassment and access to gear designed to fit them and protect their safety in the field, Hanifan and other firefighters that The 19th spoke with said.

Among women and nonbinary firefighters interviewed, day-to-day knowledge about the work — like how to adapt techniques designed for men and which clothes and accessories to avoid — typically spread by word of mouth.

That being said, every department is different, has its own budget, and has a different culture. Several women told The 19th that their gear had been fitted specially for them and that they had never experienced harassment from their peers.

Having data on hand about what women firefighters need, and what they experience, is crucial to make successful requests to manufacturers and the industry at large for needs like well-fitting gear, Hanifan said.

“It’s easy to go into a room and say, I feel I want this or flow off of emotion. But if we don’t have the data and the research to show the facts, it’s a little harder to justify,” she said.

Women and nonbinary firefighters told The 19th that better benefits, better pay, and more respect on crews would get more women to join — and stay — on the job. Several described feeling like they needed to prove themselves, or work several times harder than the men, to be recognized.

Bailey Exton, a 33-year-old mother of two and former wildland firefighter who spent time in the Black Hills National Forest, said she was the only woman on the Bear Mountain handcrew — a mix of temporarily and career wildland firefighters — when she first joined in 2016.

“They were not very excited about hiring a woman,” she said. She wasn’t the first, but it felt like the men walked on eggshells around her. She remembers that nobody spoke to her on her first day — a theme that continued for at least two weeks. “When you’re in an environment like that, for months and months and months on end, it really does start to wear on you,” she said.

On top of lacking emotional support, a lack of material support made the job harder. Exton made around $12 an hour when she first started on the crew, plus overtime. She had to pay out of pocket to get an X-ray for a broken toe halfway through the season, since she didn’t qualify for health insurance as a seasonal employee.

“To really be on call 24/7 for several months out of the year, to not have benefits, it does make it difficult to stick around,” she said. The uniforms were all designed for men, so she wore special boxers and leggings to protect her legs from the ill-fitting clothes.

“Women are coming into the fire service with force, and they’re not going to stop,” she said — and they need the respect and proper equipment to be able to do their jobs.

Selby, 41, who is nonbinary and spent most of their 20s on hotshot crews in California and Colorado (followed by helicopter duty in Alaska), said they left their first crew because of sexual harassment. They identified as a woman at the time and described being singled out by superiors and being berated by crewmembers after going to human resources for help.

“I couldn’t relax on a hotshot crew ever again,” Selby said, even though their second crew in Southern California was a comparatively better experience. The Forest Service and other agencies need to seriously enforce no-tolerance harassment policies, they said. “They need to believe people when they come forward.”

Amanda Monthei, 30, a public information officer on call with the National Parks service based out of the North Cascades National Park, said bringing more women onto crews is essential to ensure respect.

“If there’s only one woman on a crew … you don’t have an ability to change the dynamic,” she said. Whereas if two, three, four or five women join a crew, the guys begin to change their behavior — and women feel like they have more support and don’t feel as tokenized.

“You end up just with this mindset of, who’s gonna be here to help me … who’s going to be my advocate if something were to happen?”

Other firefighters said they had good experiences with men on their crews — including Donna Wood, who described her crew as some of the most passionate people she’s ever met.

Wood, who first started working in fire in her 30s, has spent a little over a year at her first firefighter job with the Ocean City-Wright department in Florida. She said that women don’t need to prove themselves or act tough to do the job.

“You can be soft-spoken, you can be silly, you can have a goofy personality,” she said. “You don’t have to have this hard exterior that people think that they have to have as a female.”

Wood added that people tend to have their own preconceived ideas about what a woman firefighter should look like.

“I think in people’s minds, they have, you know, their own opinion,” she said. “When you don’t fit the mold of something … people just take a little bit longer to come around to you.”

That happened with her crew. It took a little bit longer to feel like she was “part of the family,” compared with some of the guys. She’s gone out of her way to connect with spouses who were nervous about their husbands working with her. ”Throughout time I’ve had to explain myself, and I don’t feel like guys have to do that.”

Mia Shankle, 18, started the Rapid Valley student resident program as a volunteer firefighter/EMT at the end of June. She’s one of four students who live and work at the station — and currently the only woman — at the program based just outside Rapid City, South Dakota.

She has her own dorm and her own bathrooms at the new facility and says the guys don’t treat her like she can’t do the job, but she does feel a certain pressure to prove herself. She’s also trying to maintain a healthy work-life balance.

“I want them to see me as strong, as independent, as not too emotional,” she said. “I feel like I put a ton of pressure on myself.”

One-on-one mentorship, or learning from another woman who’s gone through the trials by fire, can be one of the best ways to get into the job. Wolf was that person for Shankle.

Wolf met the now 18-year-old in December 2020 on a medical call with the Battle Creek crew. After Shankle’s mom introduced her daughter as a future EMT who wanted to get involved, Wolf wrote down her number on the back of a scrap prescription and told her to get in touch.

Shankle, then a senior in high school, called Wolf two weeks later and came down to the station for a tour.

“After talking to her once or twice, I was like ‘You can do this.’’”

Several firefighters reflected that one of the best parts of the job is seeing things that most people never get to see — like witnessing forces of nature up close.

“Our world depends on this destruction. It depends on going through these cycles, such as with fire,” Exton said, describing prescribed burning or “good fire.”

“Have anyone go out to a forest that was burned the previous year, you go out a year later … and the trees that have been there for hundreds of years that were old and dying and starting to fall apart have been burned and made way for that new growth,” she said.

Within firefighting, some of that new growth is still trying to flourish, as more women enter the field and some of the old ways are burned away.