In the 72 hours since Texas passed the country’s most restrictive abortion law and the Supreme Court declined to intervene, the White House has been scrambling to figure out a federal response to what it calls “an unprecedented assault” on abortion rights.

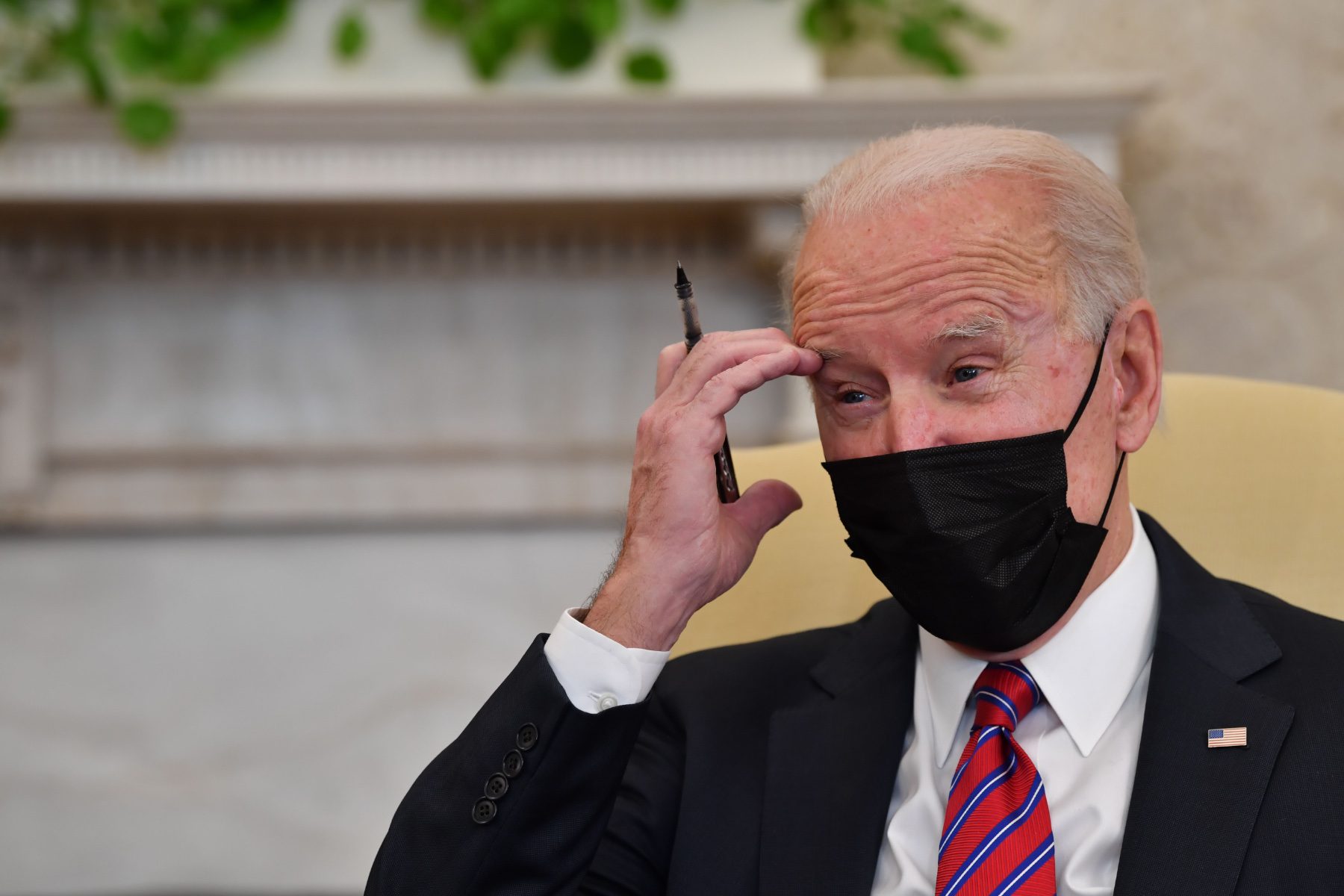

President Joe Biden has said his administration is exploring a “whole-of-government” response to the law, which took effect Wednesday. Attorney General Merrick Garland has signaled the Justice Department is “evaluating all options to protect the constitutional rights of women, including access to an abortion.” And the White House Gender Policy Council and the White House Counsel met Friday with a dozen reproductive rights activists to strategize on next steps.

But it’s still unclear what the White House can or cannot do to mitigate the law’s impact — beyond using the bully pulpit to condemn Texas’ actions and call on Congress to act.

The adminstration’s focus is on responding with legislative and policy options to both preserve abortion access for Texans and to address the “vigilante nature” of the law, which awards at least $10,000 to anyone who wins a lawsuit against a person who helps someone access an abortion after six weeks.

White House officials said the administration is also “actively engaged” with congressional leaders crafting federal legislation and will reach out to activists in Texas for guidance on how they should proceed at the local level.

Biden on Thursday issued a harsh statement in reaction to the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision allowing the abortion ban to remain in effect. He said the law’s “aid and abet” clause in particular “unleashes unconstitutional chaos and empowers self-anointed enforcers to have devastating impacts.”

The president said the Supreme Court’s decision “requires an immediate response,” and that his administration will also weigh what the Justice Department and Department of Health and Human Services can do “to ensure that women in Texas have access to safe and legal abortions.”

Asked if the administration was caught flat-footed by the Supreme Court’s decision, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said on Thursday: “We certainly know the makeup of the court, but we try to stay out of the business of making predictions.”

Andrea Miller, president of the National Institute for Reproductive Health, said there are always levers of power the executive branch can pull. She pointed to the way the Obama administration ushered through the passage of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act in 2009 after the Supreme Court ruled that pay discrimination claims could only be brought in a narrow window, or the way the Department of Justice has historically stepped in when voting rights have been limited by the states.

“When the Supreme Court failed to act, it is now imperative for the president to do so,” she said, “and the president and Congress have the authority to act.”

Congressional Democrats, meanwhile, are vowing to pass federal legislation to enshrine abortion access nationally. On Thursday, Speaker Nancy Pelosi signaled that the House would vote on the Women’s Health Protection Act, which would create a statutory right to abortion care, effectively voiding restrictive state laws like Texas’.

Psaki declined to say whether Biden will back that specific bill, adding that the administration is “looking at a range of options.” She said he plans to talk to congressional leadership about federal legislation that would make abortion legal, though she did not say when or whether that conversation is scheduled to take place.

It is unclear whether such legislation would pass in the deeply divided Senate, where it would need 60 votes to get past a filibuster. Thus far, not even all Senate Democrats have signed on as co-sponsors.

Democratic Sen. Patty Murray of Washington — the chair of the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee and the assistant Democratic leader— tweeted on Thursday night that she would use “every tool in my arsenal” and “every ounce of influence I’ve got” to protect abortion rights. A spokesperson for Murray confirmed that she is currently looking at all possible options in terms of federal and legislative responses.

One action that may be possible at the federal level involves the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is in the midst of reviewing restrictions on mifepristone — one of the drugs used in medication-induced abortion — as a result of an ACLU lawsuit challenging those restrictions. The FDA, which must respond to the suit by November 1, could lift some, if not all, restrictions on mifepristone. One of these restrictions requires physicians to personally dispense those drugs to patients, a provision that is temporarily suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such a change would be unlikely to make a difference in Texas. The state already bans the use of telemedicine to access medication abortions, and a new bill poised to hit Gov. Greg Abbott’s desk would ban the use of abortion-inducing medication after seven weeks of pregnancy. Presently, per FDA guidelines, medication abortion is available in Texas up to 10 weeks.

“As a researcher, I am both buoyed by the data we have on the safety and effectiveness of medication abortion and the suspension of the” in-person dispensing requirement, said Caitlin Gedts, vice president of research at research group Ibis Reproductive Health.

An end to the in-person dispensing requirement would open up the option for people to purchase abortion medication by mail from online pharmacies, “but getting abortion pills via mail will still be dependent on where you live,” Gedts added.

Psaki said the Biden administration is already worried about copycat bills in the wake of the Texas law. Florida, Nebraska and North Dakota have all signaled interest in similar legislation since the law took effect Wednesday.

And though Virginia Democratic gubernatorial nominee Terry McAuliffe suggested in an interview Thursday that companies including Hewlett-Packard, Dell and American Airlines move to Virginia in protest of the restrictive new Texas law, Psaki said a boycott of Texas is “not a call we’re making from here.”

Miller, with the National Institute of Reproductive Health, said that getting blue states to pass new laws protecting abortion access — such as New Jersey’s Reproductive Freedom Act, which would codify Roe v. Wade throughout the state — will be especially important in the immediate future, as more and more people travel out of their home states to safely access abortions. In the absence of a federal law guaranteeing abortion access, having a network of states with such laws on the books is critical, she said.

“Right now it’s about a combination of what Congress can do, what the executive branch can do, and then hopefully putting out a wake-up call in the states to pass new laws that safeguard abortion rights in the first place,” she said.