If you or a loved one are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 74174.

The news reached Julie in August: A fellow soldier whom she had once considered marrying had died by suicide after a long battle with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“He had been asking for help, but no one ever reached out to him,” said Julie, a 37-year-old member of the Air Force who asked not to have her last name published because she is still on active duty. “We get these questionnaires constantly,” she said, referring to surveys about mental health and suicide risk, “but they seem to be a formality and I really question whether someone is reading the responses.”

Julie learned of his death as American troops rushed to evacuate a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan — a chaotic, heart-wrenching exit that was followed shortly by the 20th anniversary of the 2001 terrorist attacks that had set off two decades of conflict. It was all too much in a matter of weeks. Julie, who had discarded plans for a career in theater and joined the military shortly after the 9/11 attacks, spent the weekend of September 11 alone in the woods, where she could avoid reminders of the forever war altogether. She reflected on “what it all meant, what my decision meant and what other people’s decisions have meant.”

That war, and the one in Iraq, carried a price that many veterans and their families continue to pay: As Afghanistan and 9/11 moved into the center of news coverage, a majority of surveyed service members, many of them women, reported new or worsening symptoms of trauma and grief, according to outreach conducted by the counseling website Onlinetherapy in late August.

The end of combat does not mean the end of suffering, and veterans are keenly aware of that. Even through the American troops’ final moments in Afghanistan, Julie said she was desperately trying to help an Afghan interpreter’s family escape, but the Taliban targeted the family and their house was burned down.

“I just see nothing but voids,” Julie said. “All the things that didn’t happen. I think about the Afghans. We didn’t get them out. There’s just one big void, and now it’s defined 20 years of my life.”

The pain is not limited to those who deployed; veterans’ loved ones, too, have sought help for themselves.

During the Taliban’s final advance through Afghanistan, Carter Barnhart, the founder of the online mental health clinic Charlie Health, received a call from a military base in Washington State. It was a young girl; her father had died while serving in Afghanistan, and she was struggling to understand what he had died for.

“The images and headlines are overwhelming,” Barnhart said. “They remind her of the war her father fought in and where he died. How do you possibly reckon with grief like that without help?”

How do you possibly reckon with grief like that without help?

Carter Barnhart, the founder of Charlie Health

Danny Taylor, an addiction prevention specialist and counseling therapist with OnlineTherapy.com, said the current news cycle can be a painful reminder that triggers traumatic memories. Veterans — and their families — need physical, mental, social and spiritual support, he said.

And then, still shrouded in stigma, there is suicide. Suicide rates in the veteran community are staggeringly high, and mental health experts argue that the federal government could be doing more. The number of military suicides since the terrorist attacks is four times the number of those who died during military operations, according to a report published in June by Brown University’s Watson Institute. More than 7,000 Americans died in combat, while more than 30,100 active duty military and veterans died by suicide in the same time period.

After surveying 1,250 Afghanistan war veterans in late August, OnlineTherapy.com found that men are slightly more likely to say they are experiencing new thoughts of suicide or that their thoughts of suicide have worsened. Women are more likely than men to say that their anger outbursts are getting worse, according to the study.

Still, women veterans are more than twice as likely to die by suicide than women in the general population, according to data from the Department of Internal Affairs. In addition, nearly half of women who used the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) received mental health diagnoses, compared with only 26 percent of men. The VA has also found that LGBTQ+ veterans experience twice the rate of depression and suicidal ideation when compared to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts.

The report did not identify a single cause for the steady increase in military suicides — which have been increasing for decades — but suggested several factors, including a result of diminished public support for the war, a sexual assault epidemic in the military’s ranks, a culture of toxic masculinity and easier access to firearms.

Any loss of life, whether in combat, as a result of injury or by suicide, has ripple effects. Loved ones left behind are forced to confront their own grief and trauma — a lifelong process.

Bonnie Carroll, the founder and president of Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS), a nonprofit dedicated to supporting anyone grieving the death of a military loved one, said her organization immediately recognized that the end of the conflict in Afghanistan would be a particularly difficult time for military families.

“We have seen our surviving family members having a paradigm shift in how they reflect on their loved ones’ service, especially in Afghanistan,” said Carroll, who served in the Air Force Reserve for more than three decades. “For many family members, it’s been a time of reconciling the meaning and purpose behind their loved ones’ service — reflecting and reassessing.”

In 2020 alone, nearly 7,600 survivors looking for support and resources reached out to TAPS for the first time. That number — which grows each year — is expected to exceed 9,000 this year, Carroll said.

“We fill the role of providing emotional support,” said Carroll, whose husband was killed in 1992 while serving. “Grief is not a mental illness. It’s the price we pay for love, and there isn’t a pill to take or a bandage to put on it.”

And while Carroll was careful to point out that grief and trauma were separate, she noted they could often coexist.

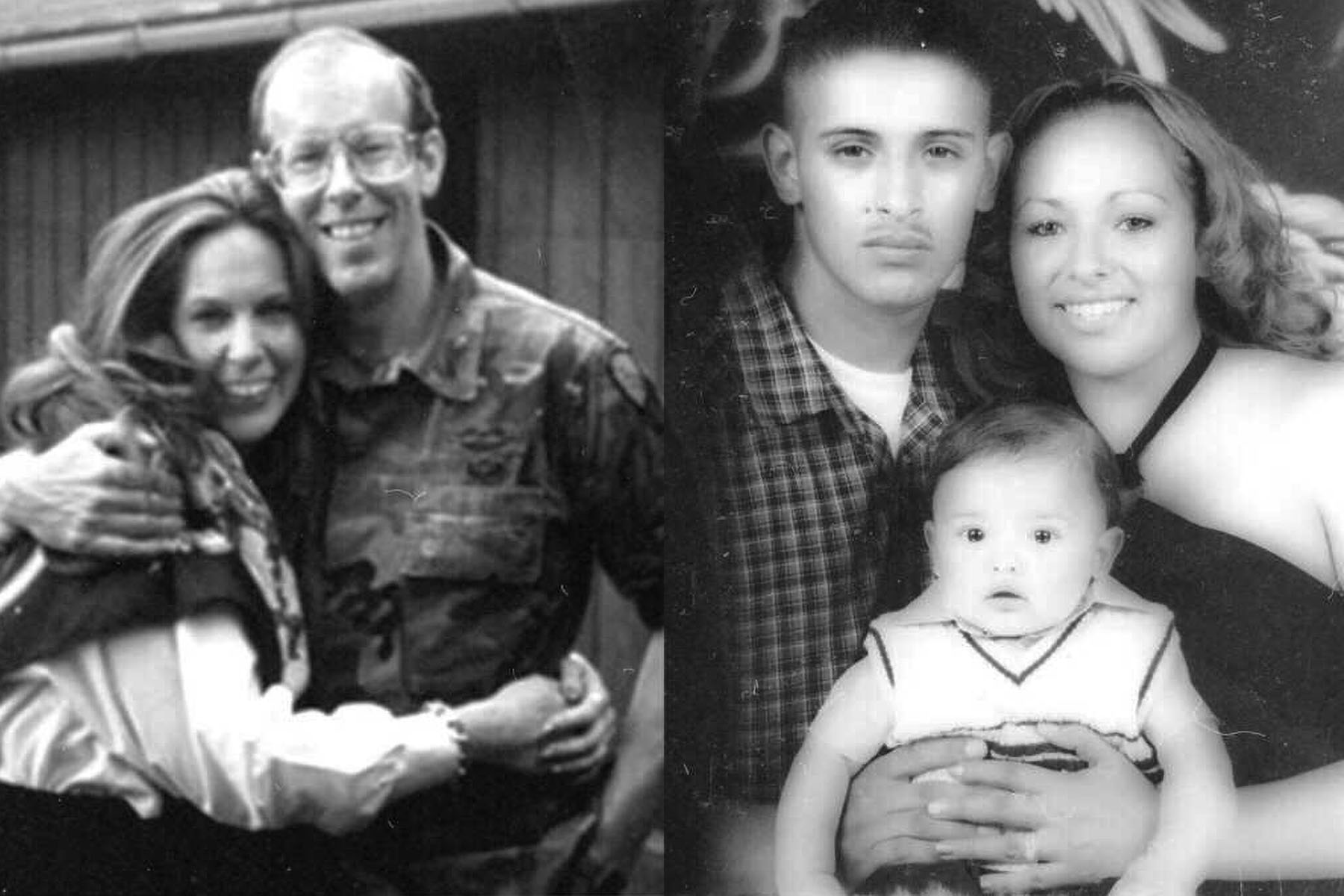

Lesliee Ojeda, an Army service member, said she didn’t feel like she could talk about her anxiety or depression while on active duty following the death of her husband.

Ojeda and her husband, also a soldier, had a son in 2003, shortly before both of their units were deployed to Iraq.

He was killed in May 2004.

“I had to be strong,” said Ojeda, who continued to serve in Afghanistan and Iraq and was on active duty until 2015. “I couldn’t tell anyone I was having anxiety, and on convoys, I just had to suck it up.”

This silence is common.

“When mental health issues occur, we hate drawing attention to ourselves because there are still people who think you don’t belong in the room,” Julie said. “And you don’t want to be a ‘problem child.’”

It wasn’t until Ojeda returned from Afghanistan in 2012 — when her son was old enough to start asking questions about the father he never knew — that she was forced to face her own grief. She said it took her nearly a decade to reach out to mental health counselors or even discuss her loss because she knew it would affect her military career and how she was seen by leadership.

“Even though I had tried so hard to deal with everything on my own, I didn’t want my son to suffer or not have the resources,” Ojeda said. “As he got older and went through his own depression and grief journey, I wanted that support system.”

Now, Ojeda serves as a TAPS mentor to military children who are on their own grief journeys.

In a recent conversation with other women veterans, Ojeda said they discussed the difficulties of reentering the civilian sector, the tendency to “make ourselves small to belong,” and the longlasting repercussions of the widespread sexual assault and harassment problem within the military.

“A lot of people are angry and upset that mental health has been put to the side for so long,” Ojeda said. “Now veterans are going home, leaving the military, and in that initial year they fall into a depression because they feel like they lose a sense of community.”

Kenneth Marfilius, an assistant teaching professor at Syracuse University and a veteran of the U.S. Air Force who served as a mental health provider, said he has heard from many veterans from his cohort and others that are still serving.

“We can do more,” said Marfilius, who specializes in military mental health, veteran social work, suicide prevention and military culture. “We are a very reactive society, and I believe it’s in our best interest to view the veteran across the lifespan.”

Taylor, from OnlineTherapy.com, said that kind of holistic support should include funding health supports and letting the veteran community “speak to their pain” and tell others what they need.

The psychological impact of war often extends past those who served to those who are closest to them. Barnhart, whose clinic largely serves teenagers and young adults, said she’s heard countless stories from children and families of veterans who are experiencing “unimaginable trauma and grief.”

-

More from The 19th

- Was the forever war worth it? Women veterans reflect on the past 20 years

- ‘I wish more Americans could see’: How two women senators secured bipartisan support for a military sexual assault bill

- Sen. Tammy Duckworth discusses Vanessa Guillen, condemns politicization of the military

Barnhart called on the federal government to provide more funding to mental health resources and counselors in public schools across the country and called for policymakers to advocate for budgets that provide students with equitable mental health support.

Charlie Health in August began providing free, virtual mental health assessments to veterans and their families, particularly military children living on military bases, she said. Many patients with deployed parents reported struggling with anxiety — unsure of where their loved ones were or if they were safe. Others were navigating the grieving process while facing financial difficulties, made more acute by the pandemic.

Nicole McMinamin, another veteran and TAPS mentor for military children, said she always reminds these children, ages 4 to 18, that their parents helped people and did not die in vain. McMinamin served in the Army for 16 years on active duty, with tours in Afghanistan, Iraq and Southeast Asia, where she worked in mortuary services collecting fallen soldiers and bringing them home to their families.

“It’s hard to get veterans and their families to talk sometimes,” McMinamin said. “There’s a lot more that need more help than they’re willing to admit.”

Like many of the hundreds of thousands of women who fought in Afghanistan and Iraq, Julie had a long, challenging mental health journey. There was a constant fear of retribution in the military, a system that “should be embracing the fact that what we do for a living is going to cause mental health issues,” she argued.

“I had a girlfriend in college who I had to stop dating because it was the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ period of time,” Julie said, referring to a Clinton-era policy that said LGBTQ+ Americans could serve as long as they kept their sexual identity a secret. “I gave up theater, a loving relationship and my mental sanity.”

She had struggled with depression before joining the military, she said, but kept it a secret after enlisting because of the stigma surrounding the illness. For a time, she worked at a suicide hotline where counseling was mandated. But it wasn’t until she was sexually assaulted by a superior and turned to substance abuse that she received formal help from the U.S. military.

“The sexual assault investigation was settled out of court,” Julie said. “Then, and only then, was I able to get the help I needed. It took being sexually assaulted by the military, and that’s the only reason I’m mentally stable today.”

There were people in her office who never spoke to her again, but Julie said she is seeing more military women all over the world coming together to talk about mental health, changes in maternity leave and other initiatives.

“Social media, for all its ills, has allowed us to see each other,” Julie said. “And there are profound impacts. You can know that you are not alone and speak out without fear because someone will tell our story.”