As Team USA women gymnasts took to the mat, the beam, the vault and the uneven bars during the Tokyo Olympics, it marked the first time they had returned to the world stage since the conviction of Larry Nassar.

For 18 years Nassar was the doctor for the U.S. women’s national gymnastics team, during which time he sexually abused hundreds of athletes who came through that program and the one at Michigan State University, where he also worked. His trial and sentencing was marked by the testimony of the “sister survivors” who spoke to what Nassar had done to them and so many other women athletes for so long, seemingly under the watchful eye of USA Gymnastics. He was ultimately sentenced to 40 to 175 years, with no chance of parole — a guarantee from the judge that he would die in prison.

But the shadow of his abuse and longstanding presence in USA Gymnastics (USAG) still looms large. Simone Biles, the only member of the current Team USA to have reported suffering Nassar’s abuse, suggested to “Today” that it could have played a role in her sitting out of several events during this year’s games. Even with Nassar behind bars, Biles is living proof that the impact of sexual violence doesn’t simply end with a judge’s orders.

Ahead of the Olympics, The 19th spoke to four of the “sister survivors” about watching the first Olympics since Nassar’s sentencing, the future of the sport and the people they’ve become beyond their association with the case.

The interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

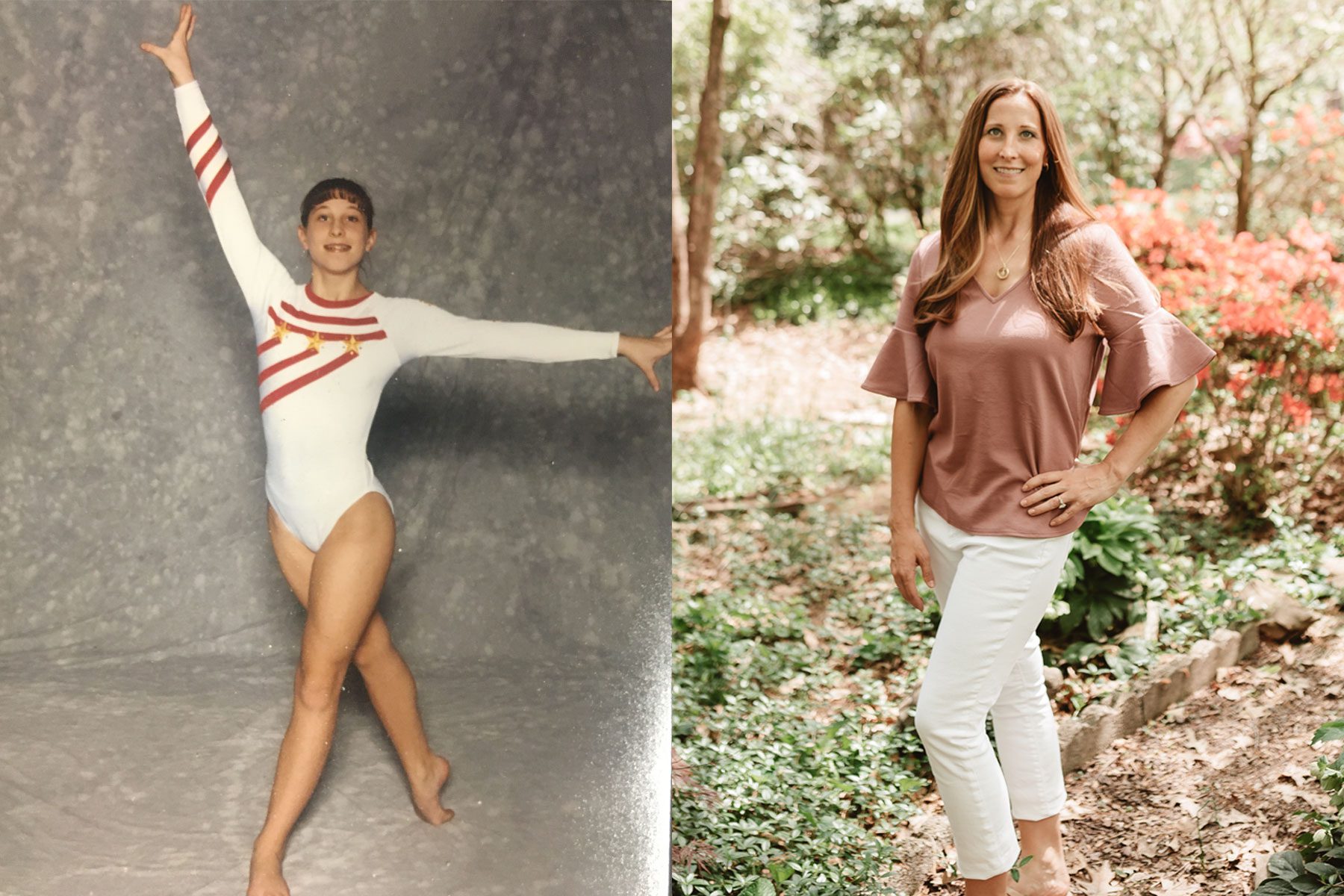

Emily Meinke, a stay-at-home mother, flew from her home in Florida to give an impact statement at Nassar’s sentencing in 2018. The 40-year-old former gymnast was first abused by Nassar while training at Great Lakes Gymnastics Club in Lansing, Michigan. She volunteers with RISE, a nonprofit supporting survivors of sexual abuse.

I started gymnastics at age 3. I started seeing Larry when I was 11 — that’s when I had my first major injury. That’s when the abuse started for me. I was very young. 2006 was the last time I saw [Nassar] in the clinic and I was 25 at that time. So, that’s almost 15 years of my life of seeing him in the gym and in the clinic.

I buried it all until the trial started.

At that point, everything came flooding back to me. When they first started speaking out, so many people were asking, “Is this abuse? Is it not?” It was a struggle all the way through. I knew in my heart that the sisters that had already come forward needed support and that the more of us who came out in support of what they were saying would only help their cause. But I did not decide to call anyone until the impact statements were being read in court.

I was living in Florida and watching it all from my computer as that first round of impact statements were being read. I thought, ‘This is me and they are telling my story over and over and over again.’ I saw my old teammates up there and I thought, ‘This is my life.’ I called and flew up there and gave my own impact statement on the last day of the sentencing hearing. I pushed everything down for so long and then it was in my face.

My husband always sets the DVR to tape all the gymnastics things for me whenever they’re on TV and I have to tell him that I have to be in the right mindset to do it. I can’t just turn it on and then turn it off and go about my day. If I’m not in the right mindset, then I’m resentful, angry, going through a million different emotions.

With the Olympics, I am so conflicted. I love Simone [Biles] and she’s a survivor, so I obviously support her 1,000 percent. I will watch it because gymnastics is my history — but it’s hard to watch because of the stance that USAG has taken and their lack of responsibility still in everything that has happened. I did feel betrayed by them as well. Larry was doing this at USAG events and I feel that they’re responsible for this as well. Everyone there comes through and says they want to make the sport safer, but they still haven’t acknowledged their role in this whole story and the unfolding of the abuse and how it was enabled and went on for 20, 30 years. It went on for such a very long time.

Right now, we want to encourage the positive parts and how well Team USA is doing and is projected to do. We want to celebrate these athletes and not have a cloud that hangs over this. But at the same time, the Olympics are an amazing platform to continue discussing the needs that are necessary to change the sport. There are so many positives happening in the sport right now and the athletes there now weren’t all involved in the Nassar thing. It’s not fair to them to focus only on this one aspect of USAG, but it still feels critical in my mind.

I have a one-year-old daughter and at this point, there is no way I would put her in gymnastics. We’ve seen story after story come out about coaches who have sexually and physically abused gymnasts. I wouldn’t feel comfortable leaving my daughter at a gym right now. It makes me really sad, because that was my passion for 15 years of my life and now I can’t get excited about it. When I do watch it, I think about how I would love to take her to a mommy-and-me gymnastics class. But that’s how it started for me — I was just a 3-year-old jumping on the mat and playing in the foam pits. But I got good fast, and that got me in the club system. And that’s my fear. What if I take her and she has fun and she loves it, and she’s good and they want her to compete? That scares me if I had to make that call. I don’t feel comfortable at this point having her at a gym at a competitive level.

For that to change, it would really start with someone at USAG taking responsibility for and admitting to the wrongdoings that happened in the organization. We have seen a parade of people take over the post of the presidency there and every single one of them, it’s always a one-sentence, “Yeah, we need to do better.” It feels like they know they need to say these things to make all these people asking questions go away. They’re always saying, “Let’s look to the future.” But I don’t feel like there’s any motion behind any of it or any quest for answers or any real effort to make comprehensive changes across the board.

Alexandra Bourque, 30, was abused by Nassar from the age of 11 until she was 15. The former gymnast co-owns Brightlytwisted, a tie-dye clothing business, with her parents in Detroit.

When we moved our store to Detroit, I made a butterfly dress for the store window out of leftover material. I made one butterfly for every girl who had come forward and spoke out about the abuse by Larry. It became a cathartic thing for me during this time when I wasn’t able to focus on the business side of work. It was like a thank you note for letting me feel everything I needed to feel and call recognition to all the women and girls who were trying to do the same thing. I found a lot of comfort by knowing I was a part of this group of women who all share the same experience.

I had stayed quiet about my involvement in the Nassar case for a few months before I even let my friends and the rest of my family know. People say I’m just doing all of this for attention, but I was really hesitant about speaking about any of it publicly. What gave me comfort wasn’t saying it aloud, but knowing that after I did, other people could come to me and say what had happened to them and I could acknowledge the trauma that they had been through. But it’s challenging — to talk about this, you have to unearth everything you’ve been through in order for other people to be better and that’s what feels so different about our group of women. There’s a commitment to providing space for others outside of our own immediate group of survivors.

Realizing that we’re just the tip of the iceberg, and that there are so many groups of women and men who have been abused by this institution and that not a lot of change is happening, has impacted how I react to it all. There’s been so much hiding and covering up by others. And as someone involved in it, you feel like you can’t stop. You don’t get to stop being a part of this. This is your life now. And right now, it feels like we’re gearing up for another fight with this institution.

I am really excited to watch the Olympics for the first time again because he won’t be there.

Alexandra Bourque

Gymnastics as a sport is still tied in the shadows of all of this. It’s a shame because it’s an incredible sport on its own, separate from all of this trauma. I get frustrated when [Nassar] is brought up in conversation during commentating at things like the Olympic trials. The media is constantly focusing on that versus the greatness on display. These are gymnasts who have achieved so much excellence, and their names are still attached to Larry Nassar. That’s hard to watch. Their names are attached to being Olympians, but there is also so much stigma around what it means to be a gymnast Olympian.

The feeling of soaring through the air is unlike anything you can describe. I love the sport. I miss it every day. I am really excited to watch the Olympics for the first time again because he won’t be there. I couldn’t watch it when he was there. I trained to be an Olympian. I trained with the Karolyis. (Bela and Martha Karolyi are the legendary and longtime Team USA gymnastics coaches who faced accusations of failing to report Nassar’s abuse.) As someone who knows what it takes to make it to the Olympics, it’s a relief that one bad part is now gone, but Larry wasn’t the only one who created this. He was enabled and allowed to do this and there are a lot of people and things that still need to be replaced. I do these interviews so that people will know my name and if they need help, they can then find me. Maybe I can help someone else find peace.

Danielle Moore trained at the Great Lakes Gymnastics Club, where she was abused by Nassar. Moore, 36, now works as a clinical and forensic psychologist and is a board member of the Army of Survivors, which provides support to athletes who have been sexually abused.

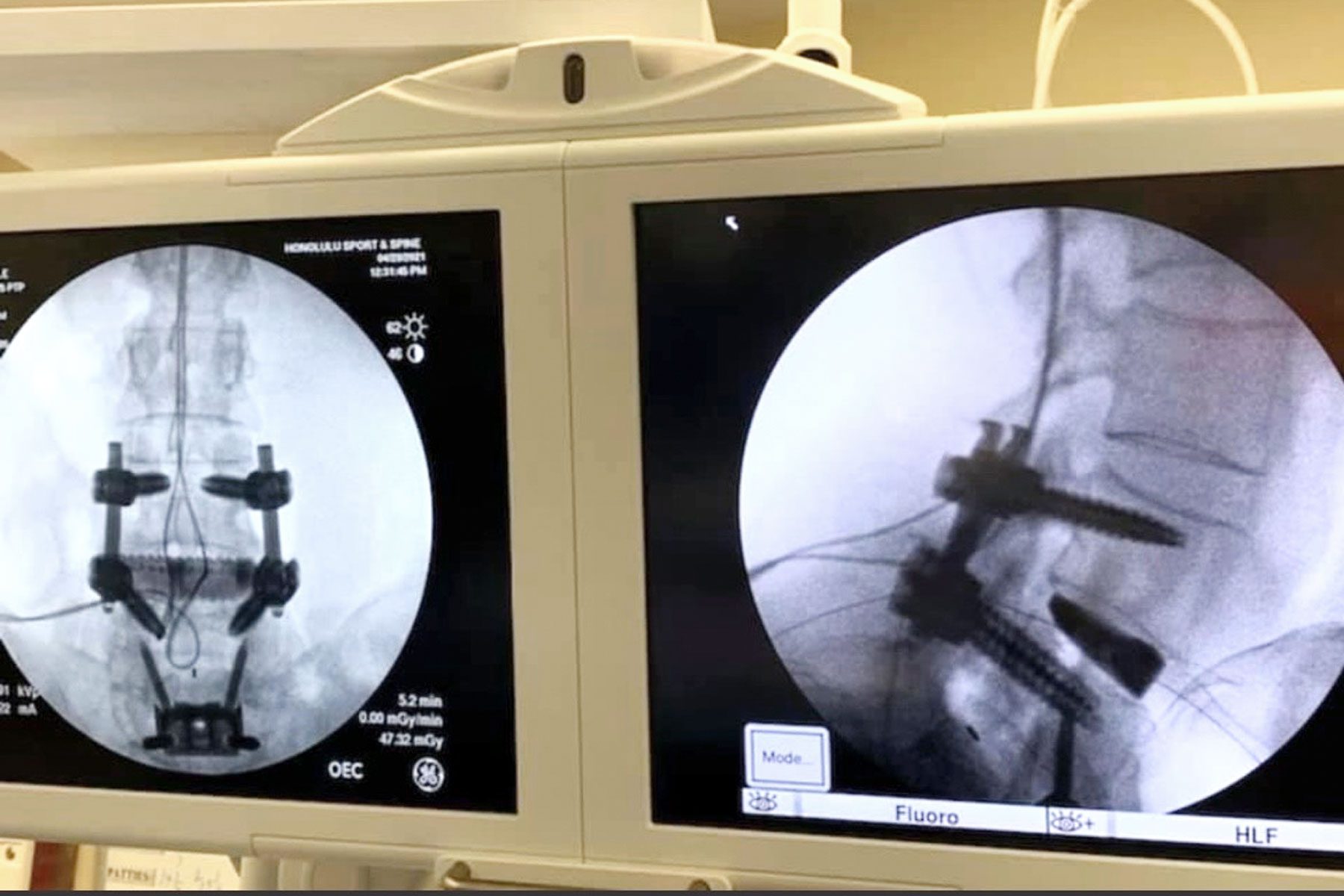

I had a herniated disc when I was a 10-year-old. That’s an incredibly unusual injury for a 10-year-old to have, and I had to stop competing. But I love the sport of gymnastics, so I wanted to do it in high school and I ended up seeing Nassar for four years. I think if I had seen another doctor, they would have just told me to quit. It would have made my life maybe not pain-free, but maybe less so than what it looks like to have had six back surgeries by this point in my life.

After the Nassar sentencing, people said to me, “Oh it’s all finally over! You can move on!” But that’s such a misconception. Really, that’s when the healing starts.

When you’re going through that process, you’re so focused on the next step: When do I have to be in court next? What do I have to do then? How do I prepare? But you’re not dealing with the trauma. After the sentencing, that’s when things got really bad for me. That’s when things got worse. Even though there are a lot of sister survivors, sometimes the people in your immediate surroundings just don’t get it. Healing takes so long.

On top of the mental health piece, there is the chronic pain piece. Even if I wanted to go out and go for a walk as self-care, I couldn’t. Something like that would just make it worse. So it’s been a struggle. I’ve had some ketamine treatments that have really helped me with my PTSD and depression. It just feels like there has always been something else to deal with, versus being able to start to move on and free myself from it. There’s always been another obstacle, whether it’s new with USAG, with the IOC, with another stack of medical bills, with the next surgery. For me, there hasn’t been a process of healing even though I feel like I want to move forward.

The past few years I haven’t gotten the traction in my career I wanted to accomplish because of the physical stuff. That’s been a real disappointment. I originally had to quit my job when I entered the Nassar case because I was working at a prison that treated sex offenders. I thought, and my boss thought, that it wasn’t mentally a good place to be in during the trial. I have had to be out of work so much because of all my surgeries. I have had five surgeries since 2016. I also developed a heart condition because of the stress and I had to go to the emergency room multiple times.

I made the decision that the situation with Nassar wasn’t going to take my love of sports away from me. That is a huge part of my life as a former gymnast. I love rooting for a team and cheering for my country. That’s a huge part of how I grew up. I had to separate the actual sport from the systemic — I don’t want to say “errors,” because that’s too minimizing — but all of the issues that have since come up because of the mishandling of this care. I still like watching the sport of gymnastics.

When I watch, I notice that they don’t necessarily talk about the abuse specifically. They talk around it in terms of “the issues USAG has had with coaching.” The wording is always very minimizing, and I think that’s a problem with society in general. We need to start labeling these things as what they are. If you minimize them, it makes it all seem not as bad. I hear commentators say things like, “When Simone Biles spoke,” and they’re alluding to Nassar and what she has said and her return to the sport, but I wish there had been clarification on exactly what she was speaking about. Some people may not know. Those in the gymnastics community know. But those who are just fans of the Olympics and get into gymnastics every four years may not know.

Flat out say: Coaches have been abusive. Coaches have been suspended. Just say USAG isn’t just “mishandling” things, but responsible for things. Say that the organization needs to be completely restructured. Say that people who made horrible decisions are still there. Say that the people they hired are still there. Say that it needs a complete overhaul.

I hope commentators call it as it is and that they won’t be afraid to say it on TV. Even though the Olympics are supposed to be a happy time, there is so much that happens behind the scenes that people don’t know about. There is this facade of happy women and girls tumbling on the floor and it all looks very feminine and pretty, but there is just so much behind it that people don’t know.

Melissa Hudecz, 36, is a former professional dancer and a survivor of Nassar’s sexual abuse, which went on for four years beginning when she was 14. She co-curated the exhibit “Finding Our Voice: Sister Survivors Speak” for the Michigan State University Museum.

I am an occupational therapist. I work primarily with preterm infants. I went to college and then I had a chance to dance professionally for a few years, and did that. When I stopped dancing, I knew I wanted to go back and get my master’s. I’ve been a therapist for about eight years now.

Working with babies and parents and families in the NICU, I feel like I can relate to them on a human level from the standpoint of trauma. Having a baby in the NICU is traumatic. Being a baby in the NICU is traumatic. I try to keep babies in “rest and digest” and not “fight or flight.” It’s therapeutic for me to see changes like that in a baby, to know that I’m helping them to reset their nervous system and mitigating some of the effects of trauma long-term on their growth and development.

I think trauma and the whole experience, it changes all of your relationships. It changes you as a person. It changes how you see other people, how you see the world, how other people see you.

Melissa Hudecz

I also have two small kids — my daughter is two and my son is three. My kids were all born since everything became very public in the last few years. My son was only four or five months old when I understood what had happened to me and was watching days worth of statements in court.

After my son was born, I had postpartum depression. The trial was happening at the same time, and that was a big piece of it. When he was less than a year old, I required a partial hospitalization, but fortunately it was in a mother-baby program, so I was with other women. That was exactly what I needed at that time. Then I did another outpatient program after that and have been on that journey since.

It all has just gone by so fast with him growing up in the midst of that, and I knew I wanted another child and I wasn’t going to let my own history get in my way. I immediately had another child, and those two are my world.

I’ve done tons of therapy because what happened to me has been a constant in my life. It just never stopped for me. There’s this sense of, “Oh that happened and it’s over,” and it’s not public right now the way it was, but that doesn’t stop it from impacting you when you’re alone and driving in your car to work, or when you hear a story on NPR one day. You just never know when a movie or book will come out or you’ll hear an update on the news and even if it’s something you already know, it still hits you like a ton of bricks. With my professional development and having a young family and being in a pandemic and being in the thick of the pandemic at work — it’s just been layers upon layers of trauma. It’s been hard to get back to being in a good place. I’ve been in survival mode for so long, and it’s exhausting.

I think trauma and the whole experience, it changes all of your relationships. It changes you as a person. It changes how you see other people, how you see the world, how other people see you. It’s not over just because it’s not on TV anymore. But I’ve really tried to use my voice. As a parent of two really young kids, I just feel a responsibility to make the world a safer place for them. I want to make it very difficult for something like this to ever happen again.

For months, I have just been waiting, just filled with anxiety waiting for everything to get brought up again because of the Olympics. Part of Simone Biles extending her career for another year was her wanting to go out there and be a voice.

I think what we need to see now goes beyond USAG and the IOC, though I do think they need to have more trauma-informed reporting and investigation processes in place. But it hasn’t really been enough time to alter the culture of the sport itself because what happened didn’t happen in isolation. It required people being complicit and people being silent and people ignoring it. Whether dance or gymnastics, we’re hearing so much now about emotional abuse and the extent of what went on with coaches.

Psychological abuse is so big. And the coaches have all been abused themselves and the cycle has to be broken. This is what the coaches know and how they learned. I’m hopeful that the next generation of gymnasts and future coaches that have been through this and witnessed this will provide emotional support for athletes and not break them down, but build them up when they realize an athlete is being limited by their own thoughts and needs more counseling and support.

We need something in place not just for gymnastics, but for all kids that is about teaching mental health skills, self-care. Education has to be there for kids, for parents, for coaches and I don’t think it will come from the top of these organizations. Things just don’t have to be the way they have been for athletes to be amazing.