An ongoing theme of coverage at The 19th is about the relationship between women and power. That relationship has come into sharp focus since the birth of the #MeToo movement in 2017. While the movement began with bombshell reporting from the New York Times on Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, the campaign spread far beyond the United States and became a global phenomenon that continues to reverberate.

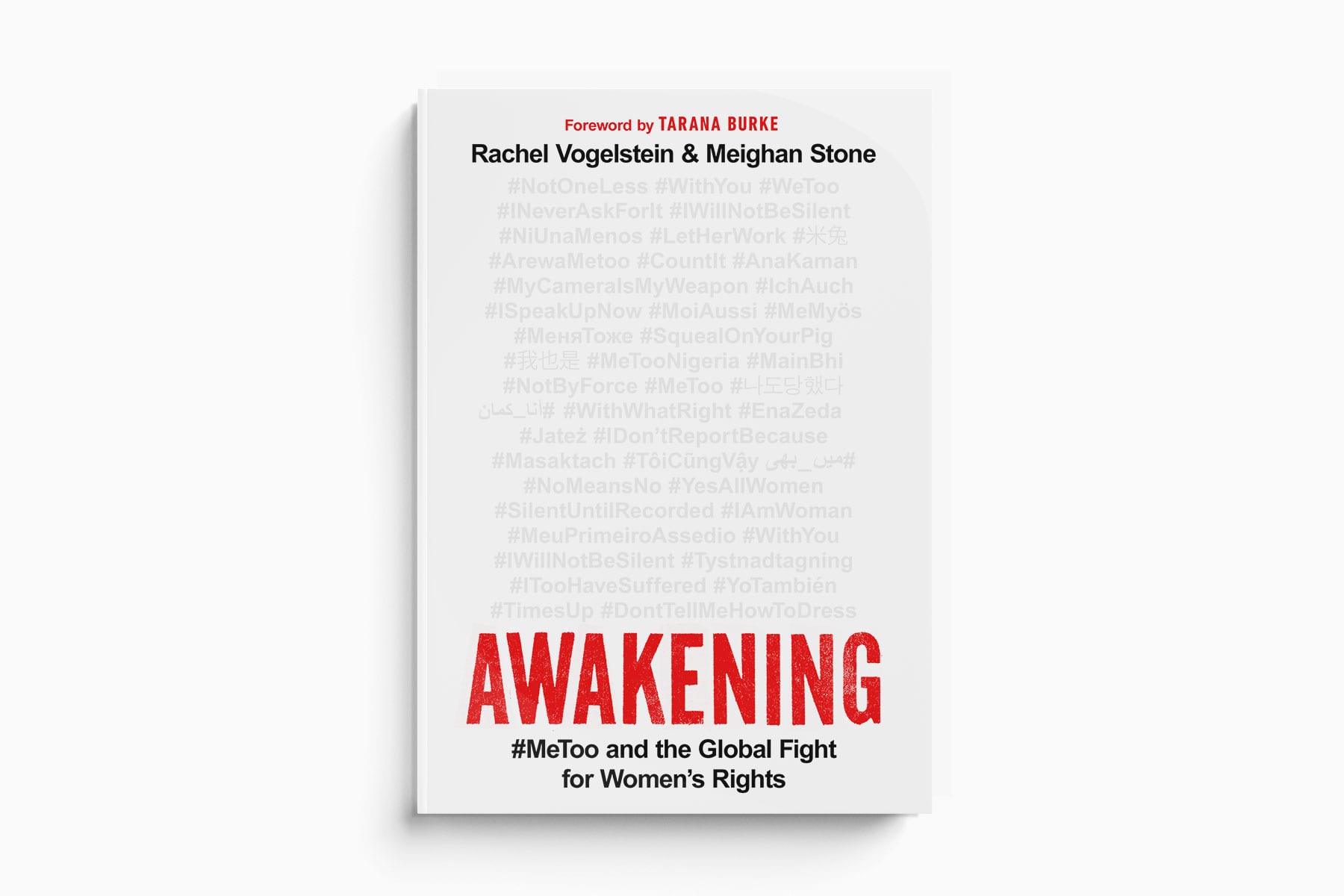

For my latest Q&A, I spoke with Rachel Vogelstein and Meighan Stone, authors of the book “Awakening: #MeToo and the Global Fight for Women’s Rights.” Vogelstein is director of the Women and Foreign Policy program at the Council on Foreign Relations and Stone is a senior fellow in the Council on Foreign Relations’ Women and Foreign Policy program.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Errin Haines: The #MeToo movement was such a huge phenomenon in the United States, but what is it that Americans didn’t know about its global impact?

Rachel Vogelstein: “Awakening” tells the story that you don’t yet know, which is about the remarkable global impact of the #MeToo movement that has spread now to over 100 countries around the world. What we found is that what started as an online campaign against sexual harassment has triggered the most widespread cultural reckoning on women’s rights in history. So we knew this was a story that had to be told.

How did #MeToo look the same in other countries as the movement did here? How did it look different?

Meighan Stone: What we found was that the core of the campaign and the movements stayed the same, in terms of being firmly focused on fighting back against sexual harassment and sexual assault. Overwhelmingly, we know that’s girls and women but not only for girls and women, but for anyone that’s a victim.

What we saw was although that central call to action remained the same, the way the campaign played out locally around the world was incredibly creative, and in many countries, because of the threat to women for standing up and advocating for their rights, courageous as well. We saw that the hashtag was customized and translated into just so many different languages. It was also hyperlocalized.

We found, for example, in Nigeria, the version of the hashtag was #ArewaMeToo — “arewa” being the household word for North — and women in the northern part of Nigeria customized a campaign to call out their particular government officials that were harassing and assaulting women. They then used it to campaign for changes in legislation to protect women and give them legal rights if they are assaulted, or harassed in the workplace.

And so we found that the power of digital organizing is that you can have a transnational movement, but then at the same time, it can be hyper-localized, you know, so women really made it their own, whether that was language or being very specific about what wrongs they were trying to right.

You mentioned an example of the creative ways that people adapted #MeToo. What about an example of a courageous story that comes to mind?

Vogelstein: This book teems with stories that inspired us, women who spoke up and in response, lost their job, or were ostracized from their communities, in some cases, were incarcerated or paid the ultimate price with their lives.

In China, I think of women there who bravely used technology to help circumvent censorship. So, for example, using blockchain technology to embed messages so they couldn’t be taken down, or getting around text-based censorship by posting images, such as emoji characters, converting banned phrases like #MeToo into a picture of a rice bowl, which is pronounced “mi” and a bunny, which is pronounced “tu.” These innovative tactics helped women overwhelm those intending to silence them. We have a lot to learn from the fight that these leaders have waged around the world.

Stone: In Pakistan, women took to the streets with their own version of the Women’s March. It’s called the Aurat March, which is just “woman” in Urdu. And many of those women actually wound up having to go into hiding after that march, because the backlash was so serious and so severe that they had real, credible threats to their lives, and to their work. These women are really standing up and continuing to fight. They truly are human rights defenders.

Why didn’t we hear these stories as the #MeToo movement was happening here?

Vogelstein: So much of the American media focused on the consequences on individual prominent American men. Even this week, we were asked a lot about the Bill Cosby release and what that says about the state of the #MeToo movement, and in our view, it’s a mistake to evaluate the strength of this global movement through the lens of what’s next for one particular prominent man. I think instead, we should be asking what’s next for the millions upon millions of women who have raised their voices around the world.

What does this reckoning look like for those women around the globe four years later?

Stone: In many countries, it’s achieving firsts. It could be the first woman to bring a case of workplace harassment, a woman named May al-Shami who’s in Egypt, she’s one of the first women to come forward and to use a new law to try to fight back about being harassed at her place of work, which was a newspaper, as a journalist.

In other countries like Tunisia, women helped write into their constitution for their new governments protections for women, including sexual harassment and sexual assault. And they’re moving forward calling out elected leaders that have fallen short or even broken the law. In Nigeria, it’s passing new legislation that protects women’s rights, it’s the violence against person acts, you know, being able to push back against university professors getting them removed for the first time in southern Nigeria, where they were demanding sex for grades. In Pakistan, the Aurat March was a first ever, to have women taking to the street in such an intersectional way there, including LGBT advocacy.

We argue in the book that what we’re seeing in this movement is also feeding real progress in terms of women’s leadership as well. We’re seeing record amounts of women run for office, really stand up and say it’s my time to lead — and from historically disenfranchised communities, even within the country. In a lot of countries, if you are from, you know, from a majority Muslim or majority Christian community, if you’re from a different faith background, you may not be able to come forward and lead in a way that would be equitable and fair, and we’re seeing women actually come forward and lead together. And so that’s really exciting to see.

What do you think are the main lessons that Americans can take from some of these other countries and how they have interpreted and adapted the movement and the example that they have put forward?

Vogelstein: This book is not about the heroic arrival of Western feminism to other countries. In the countries that we went to, women have long organized for their own equality, and in many nations, the rise in online activism actually predated the popularization of the #MeToo hashtag here in the U.S.

I’ll point to Sweden, for example, which is a country that has long been considered one of the most gender equal in the world. And yet they had an enormous movement there and a serious gap, particularly when it came to harassment and discrimination in the workplace.

Instead of publicly outing individual men who harassed and assaulted them, women there decided to instead amass their stories anonymously online in order to increase the number of women coming forward and to emphasize that this is not about a few individual bad apples, but instead is a systemic form of discrimination that affects every workplace in their country. They actually organized across 65 different industries.

And they did it with humor, they used clever hashtags that helped the movement go viral in record time. Restaurant workers posted under the hashtag, #WeAreBoilingWithRage, and healthcare workers posted under a hashtag that translates to #NowItWillReallyHurt. The unions used #NotNegotiable.

There’s a lot about the strategies and tactics employed by women in other countries that we can learn from, and the bottom line is all of us, in whichever country we reside, have work to do.

Stone: What we’ve seen is not only is intersectional, diverse, equitable leadership the right thing to do, it’s way more successful. When you have a broad based movement of women coming together, you’re gonna see change in really profound ways that both accelerate and make sure that systems are altered.

The last thing we want someone to do is read this book and just leave being like, “I heard a good story,” or, “I’m inspired.” We really want to see concrete action. The reason that we were chronicling these stories is both to learn lessons about how to do even better or deep organizing around feminist issues, but also to get support for these women. We’re not here for performative storytelling!

We also want to see changes in policy. Right now, less than one penny of every dollar goes to supporting global women’s organizations in our U.S. foreign aid. We want to see a better investment in these women and women globally. They absolutely are incredible bets and they are the folks that we should be investing in. So we want to see that change.

What were the lessons that you saw from the pandemic that affected the #MeToo movement, as we are reopening and kind of trying to get to a new normal, not just here but around the world? What did workplace harassment look like in the pandemic?

Vogelstein: COVID-19 has revealed deep structural inequalities, showing essentially that women have less power in the workplace. Women already saddled with an unequal burden of caregiving saw their responsibilities multiply, as schools and childcare centers closed, doing an average of three times more unpaid work than men. We saw rates of intimate partner violence skyrocket as many women were forced to shelter at home with their abusers, an exodus of women from the labor force as female-dominated industries were particularly hard hit.

But we also found in our reporting that despite these lockdowns and school closures, that women continued to use digital tools to post about sexual harassment and abuse and to demand change. And despite the risks of contracting the virus, many continued to take to the streets. For example, at the height of the pandemic, Argentinian women who began protesting against gender-based violence under the hashtag #NiUnaMenos — which means “not one less, which long predates the #MeToo hashtag — donned face masks in record numbers and organized marches, leveraging their newfound political power to push to legalize abortion, and their historic victory has had reverberations across Latin America.

We saw women in Iran, one of the most oppressive countries in the world to be a woman, also rise up to say #MeToo, and a number came out to make allegations against a man now known as the Harvey Weinstein of Iran, a cultural influencer, who is alleged to have harmed many women, and that’s led to the Iranian government considering a groundbreaking bill to criminalize sexual assault and harassment. The pandemic has certainly undermined women’s participation in the economy, but it has not quieted women’s voices, and if anything, we expect their voices to continue to rise as things reopen.

Stone: Digital technology is not a panacea. Women still can be harassed digitally, they can still face extreme threats digitally. But what we saw was women were still organizing for change and a number of cases and other pieces of legislation that were still in motion continue to be under consideration and fought for during the pandemic.

I think one of the most disturbing things that we saw in the pandemic was not as much workplace harassment as it was escalating levels of domestic assault and abuse. Many women were caught at home with their abusers, under great stress, trying to manage childcare, trying to manage working from home trying to just survive. For a lot of women, that was extremely dangerous, and as we know, domestic abuse can also take the form of sexual assault.

We need to make sure there are strong laws, but not just laws. That’s what we saw in the book over and over again: You can pass a groundbreaking law, but if women can’t trust that when they call the police, the police will come and they will charge that abuser and then once they’re charged, that they can have a fair hearing in a court of law the work of justice is not finished. That’s what these women are really fighting for all over the world. It’s not just the law, but the full enforcement and protection of the law.

What is it that you really want folks to be awakened to in this moment as a result of the work that you have done? What was it that you all were awakened to that you didn’t know before you started this book?

Vogelstein: We came away from writing this book incredibly hopeful. I think people will be surprised to see that, in some countries where women really face impossible odds, they are organizing collectively, rising up, and they’ve won record victories in just three years. We share stories about women who still lack access to justice, who were imprisoned, or in some cases, even killed. But what blew us away is that collectively, women keep coming anyway. After meeting these women and watching this wave of activism travel digitally across the globe, I think we cannot help but feel hopeful about the changes on the horizon.

Stone: One of the most special moments for me working on the book is when we were talking to Tarana Burke, who was generous enough to write the foreword, of course, as the mother and founder of the movement, a tremendous honor. And when we were sharing with her what some of our research had been finding in countries, you know, as diverse as Nigeria, Brazil, Pakistan, Egypt, Tunisia, China, Sweden, and there were stories that she had never heard before. And that was such an important moment, for me to be able to say we’re honoring your work and going out and really chronicling stories that haven’t been told, because media does not cover the experiences of black and brown women, and of non-American countries.

We knew that we were actually doing what we wanted to do, which was decentering ourselves, and chronicling what these women were achieving, and the great prices they were paying, and what they were succeeding in winning, these life-changing victories for themselves, but also generational breakthroughs.

I like to think of “Awakening” as an awakening of the powers that be, that collective organizing and power on behalf of women for their own equality is a force to be reckoned with. It’s not that women were awakening to the fact that they had rights or awakening that they had a voice. They’ve always known they had those things — they weren’t being listened to by those with authority.

Sometimes I like to think of “Awakening” as being the awakening of men in power to the reality that it is not going to continue as it’s been since the beginning of time. Women, as half the population, half the economy, caretakers, leaders, are no longer going to tolerate being silenced. So it’s really the awakening that this work needs to be done. And it must be done.