Virginia State Sen. Jennifer McClellan knew her bill to strengthen protections against workplace and sexual harassment was in trouble at one February meeting. She was pretty sure that the committee was going to kill it.

Her suspicion was confirmed when one lawmaker at the meeting posed a question: Would it be workplace harassment, he asked, if a woman employer asked a male employee to move furniture? The question completely missed the point, she said.

“It’s frustrating that in a body of predominantly men that some didn’t appear to really appreciate the fact that this happens every single day,” she said.

McClellan’s legislation proposed clarifying what constitutes sexual and workplace harassment, addressing concerns that cases could be falling through the cracks. For sexual harassment, it would have included a sexual advance, a request for sexual favors or any other conduct of a sexual nature. Workplace harassment would have included conduct on the basis of protected classes “that unreasonably alters an individual’s terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, including by creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.” McClellan did not intend for it to include furniture moving requests.

The proposal is among several bills introduced in statehouses this year aimed at tackling a subject that workers’ rights advocates say is fraught with loopholes in both federal and state laws, leaving employees — particularly women, people of color and LGBTQ+ workers — at highest risk.

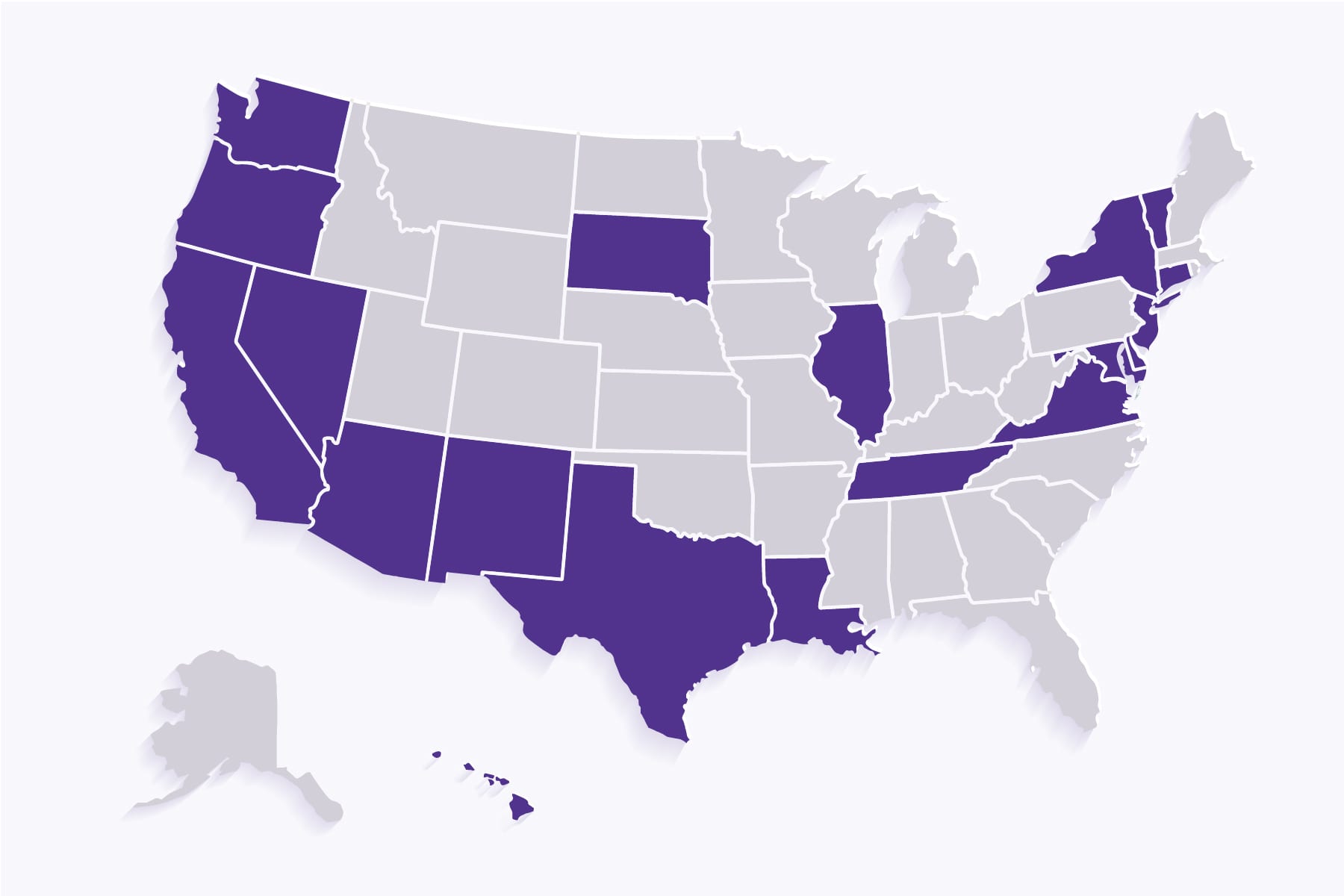

Around the country, state legislatures have enacted or strengthened laws on workplace and sexual harassment in response to a public reckoning following the #MeToo movement. Since late 2017, at least 19 states have taken some kind of action on workplace harassment, according to a tally by the National Women’s Law Center.

But there’s far more that state legislatures can do to address gaps, advocates say.

Federal law defines harassment as conduct that is “severe or pervasive” enough that it creates “a work environment that a reasonable person would consider intimidating, hostile, or abusive.”

Bills aimed at clarifying what constitutes harassment have been introduced in states including Maryland, New Jersey, Oregon, and Vermont.

Advocates say the toll of workplace harassment — which can include nonconsensual sexual acts but also other forms of discriminatory abuse — can create negative mental and physical health effects, lost wages and missed job opportunities.

Vulnerable workers — particularly Black women, women of color and other marginalized groups — remain at the highest risk of harassment because advocates say they experience forms of abuse that intersect not just with their gender but with other identities like race and sexual orientation. Some workplace anti-harassment policies just provide protections based on sex.

“You have these fixes that work best if you’re a White woman,” said Andrea Johnson, director of state policy at the National Women’s Law Center. “If you are a Black woman bringing a claim, you’re basically forced to kind of divide yourself into pieces.”

Advocates say case-by-case rulings have further muddled the legal protections around harassment, with courts sometimes setting a high bar for how much harassment must take place before a workplace is hostile.

The threshold has previously led to court rulings in New York that lawyers for alleged victims of harassment felt were unfair: One case that reached appellate court involved a male employer sending offensive emails to workers and telling a woman employee that she should get breast implants, offering to take her to a doctor. The same employer told the employee that her underwear was exposed but to not adjust it because he had been “enjoying” himself. The court ruled it was not a hostile work environment because it was “mere offensive utterance(s)” on several occasions instead of pervasive and ongoing.

In another case that reached appellate court, a male employer suggested to a woman employee that she purchase certain sexual paraphernalia. He also rubbed lubricant on the employee’s arm and called her a sexually derogatory name. While a court said the workplace was “uncivil and crude,” it was unable to conclude it constituted a hostile work environment.

A New York law signed in 2019 eliminated the “severe or pervasive” standard from discriminatory and retaliatory harassment cases. Miriam Clark, chair of the legislative committee of the New York affiliate of the National Employment Lawyers Association, said she was able to effectively shut down arguments about the bill’s potential effect on employers by highlighting that New York City had enacted similar policy years earlier without widespread impact on small businesses.

“When people are subject to unlawful hostile workplaces, their productivity goes down. They quit so there’s turnover. Employees are unmotivated. They’re unhappy. It’s terrible for business to have a hostile work environment,” she said.

Johnson said much of the oppositon is based on an assumption that women and other marginalized people frivolously file discrimination claims.

“When you start to peel back the layers of when this argument is made, against a regulation such as, ‘Do not harass your employees,’ you really start to see how deeply sexist and racist and disgusting these arguments are,” she said.

Concerns about the potential effects on business also seemed to doom McClellan’s bill. The Virginia legislature last year had passed a bill to add sexual orientation and gender identity protections to the state’s anti-discrimination law. The legislation also expanded workers’ rights in bringing forward a discrimation claim, not limiting them to when an employee is fired. But McClellan wanted to clarify further the definition of harassment.

The Virginia Chamber of Commerce was initially against her legislation but dropped that opposition when concerns about employer liability were addressed. Still, three Democrats ultimately opposed McClellan’s bill, including Sen. Chapman “Chap” Petersen, who raised the question about furniture moving. When asked during the discussion if he planned to amend the bill, Petersen said: “I just want this bill to go away.”

Petersen’s opposition helped kill McClellan’s bill, as well as another piece of legislation on workplace and sexual harassment that was introduced in the state House.

A spokesperson for the chamber did not respond to a request for comment. Petersen and two other Democratic lawmakers who opposed McClellan’s bill did not respond to a request for comment.

Not all workplaces are subject to federal protections against sexual harassment, including employers with fewer than 15 workers. They also do not cover independent contractors and other people who may not be considered formal employees. That can mean that people like domestic workers and farm workers and others in the gig economy are also left out of anti-harassment protections.

“There’s been this systemic carving out of some of the most vulnerable populations from any protection against harassment,” Johnson said.

There is also a lack of comprehensive data on workplace sexual harassment, in part because many workers who experience sexual harassment choose not to report it due to fears of retaliation. A report on sexual harassment by the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund analysed more than 3,300 requests to the organization for legal help from 2018 to 2020. More than 7 in 10 survivors who claimed workplace sexual harassment said they also faced retaliation in the form of being terminated, being sued for defamation and being denied promotions.

Carrie N. Baker, a professor at Smith College who teaches about women and gender and is a contributing editor at Ms. magazine, said legislation introduced in Congress to improve existing federal anti-harassment protections have not advanced, making states’ actions even more important.

“They have made tremendous progress in creating broader coverage and wider coverage — In other words, covering more employers, covering more behaviors, covering more employees like interns and volunteers, which federal law does not cover,” she said.

The approaches in statehouses to workplace harassment policies vary. States like Connecticut and Oregon extended the statute of limitations for someone to file a harassment claim. In Illinois and Louisiana, there are new transparency requirements for employers that record cases of sexual harassment. And in more than a dozen states, laws have limited or prohibited employers from requiring employees to sign nondisclosure agreements as a condition of employment or as part of a settlement agreement.

Mariko Yoshihara, legislative counsel and policy director for the California Employment Lawyers Association, helped advocate for a California law that went into effect in 2019 that expanded protections against workplace harassment. She said it’s important for policymakers to consider the complexities of what creates a toxic work environment.

“It’s the power dynamic, and it interferes with a person’s working conditions,” she said. “… I think a lot of people overlook how much of an impact it has on workers beyond, ‘This person is annoying.’ This could potentially make me leave my job, or want to work in a different department that maybe pays less. Or I can’t do my job well because it’s distracting. There’s so many other other effects that harassment has on an individual in the workplace.”