The boys open each class with the same mantra: “I am a king. I am a leader. I am smart. I am my brother’s keeper.”

Boys as young as 8 and as old as 13 — many of them Black — have met on Zoom Wednesday afternoons all summer to break through society’s narrow definitions of masculinity.

The “Mighty Brotherhood” workshop gives the boys, all of them living in or near Philadelphia, a place to read poetry, give compliments, write down their goals, share ways to practice self-love and talk about what it means to be a man.

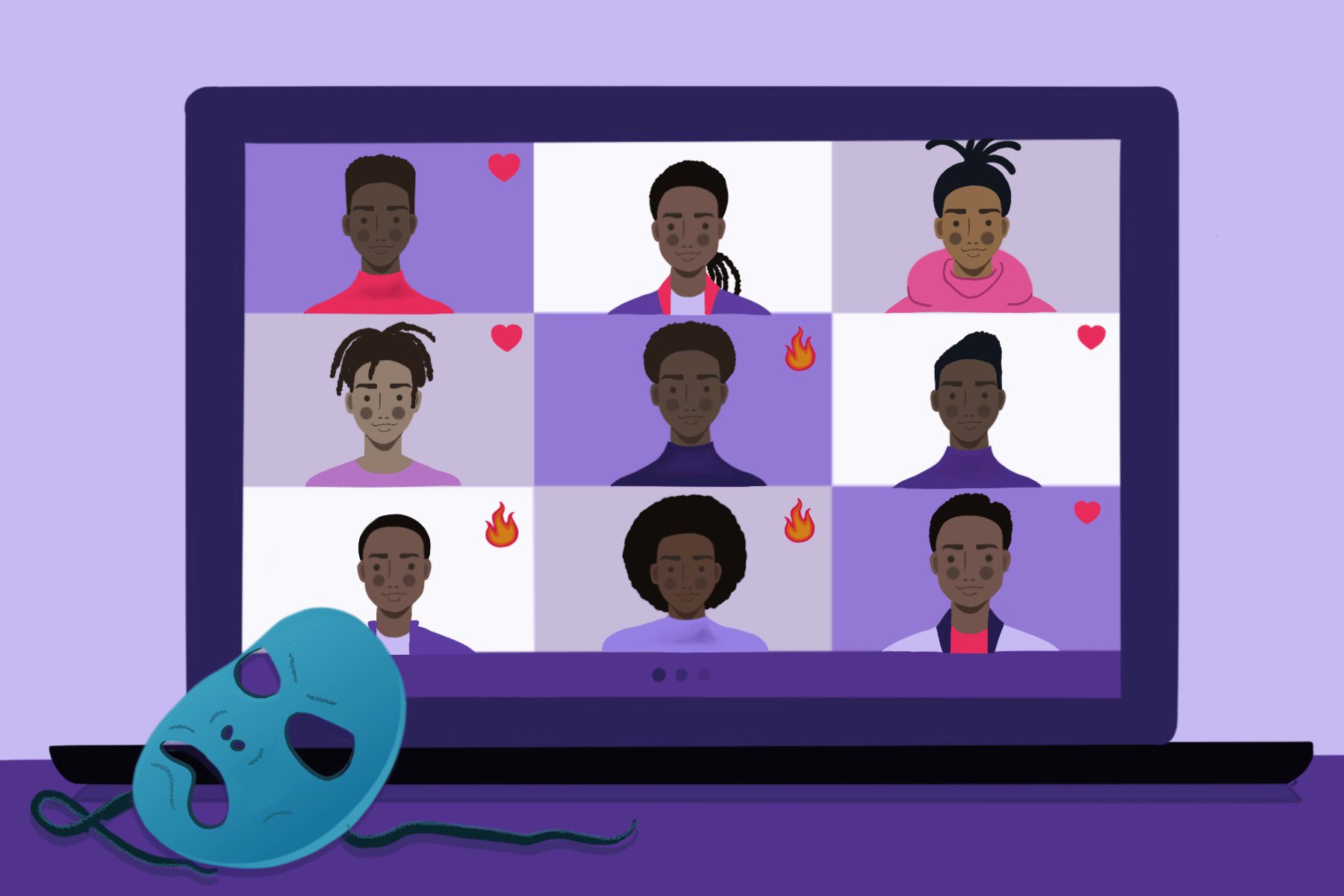

Maurice Williams, who leads the hour-long workshop, thanks the boys throughout for being brave enough to share their feelings and encourages them to send heart and fire emojis to each other, which they frequently do.

Encouraging the boys to share how they’re actually doing — “They have to give me more than just ‘good’,” Williams said — is part of how the sessions aim to foster healthy masculinity through authentic self-expression.

“Being able to be transparent and to be heard, I feel that’s one of the driving forces in how we’re able to break down that toxic masculinity and how we’re able to develop healthy young men,” he said. The 19th sat in on two of the July Zoom calls.

Boys in the U.S. are often pressured to devalue friendships, disconnect from emotions, objectify women and use violence to end conflicts as they navigate restrictive definitions of masculinity. Much of this is explored in “The Mask You Live In,” a 2015 documentary by the Representation Project, a gender equity non-profit founded by Jennifer Siebel Newsom, California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s wife.

Children’s books on healthy masculinity published within the last several years usually encourage boys to break those patterns through expressing their emotions, being compassionate, and breaking from gender stereotypes. Classes exploring masculinity — like those offered at Brown University and Duke University’s ongoing “Men’s Project” — follow those same themes, while interrogating male privilege and its consequences.

But there don’t seem to be many summer or after-school classes that reinforce healthy masculinity for young boys. “Passport to Manhood,” a program offered by the Boys & Girls Clubs of America, is one exception that focuses on maturity and self-esteem.

Fostering self-care and self-love is part of building healthy masculinity, Jenn Jackson, an associate professor of political science at Syracuse University, told The 19th. And men’s societal expectations are “particularly violent” for Black men, she said.

Black men and boys have to conform to and placate White expectations of behavior in order to avoid being singled out at school, singled out by police or singled out in the workplace, she said.

“When it comes to young Black men and performing this masculinity, the stakes are really, really high,” she said. “You can’t, as some people have told me in my research, you can’t wave your hands and be upset in public … when you look irate, you’re more likely to draw attention and you may end up in a confrontation with police officers.”

Experiences like this, Williams said, send a chilling message: “I am here, in this world, but to this world, I don’t exist. I’m not a person in this world. I can’t be seen for who I am in this world.”

Jackson has been interviewing young Black people in Chicago and 10 other cities for her upcoming book, “Policing Blackness.”

When talking to young Black men, she said, “A lot of them have articulated that there are gendered expectations around how they’re supposed to seem strong. They’re supposed to seem like they have it all together.”

I think hearing one Black man celebrate another Black man gives you space to do so as well.

Angela Bostick, whose son is enrolled in a class about positive masculinity

Furthermore, she said, the men tell her, “I don’t often have a place to be vulnerable. I don’t often have a place to be scared. I don’t often have a place to be imperfect.”

In that way, young Black men sharing self-love and self-care fostered in the “Mighty Brotherhood” sessions is an act of revolution that runs against what society tells Black boys they should be, Jackson said.

That reality of Black boys being boxed in is part of what makes the classes a “sacred space” for young Black men to be their authentic selves and express self-love, Williams said

“Some of the young men that have come in this group really have struggled with the notion that, ‘I have to silence myself’ or ‘I can’t like what I like or ‘be who I want to be because I may be judged, or I may be ridiculed or talked about because I don’t want to fit inside society’s box,’” he said.

That line of thinking, especially for men, can have long-term consequences.

The American Psychological Association’s 2018 best practices guide for helping boys and men — the first guide released by the organization — cites research over the past several decades that found conforming to stereotypical masculinity limited men’s psychological development and negatively affected their physical and mental health.

Black men especially see expectations of traditional masculinity — being strong, not showing vulnerability — as a threat to their mental health, Jackson said, citing her interviews.

Across the U.S., young men ages 18-29 are struggling the most to maintain meaningful friendships and robust support systems, even as many aspire to be less traditionally masculine, Dan Cox, the director of American Enterprise Institute’s Survey Center on American Life, told The 19th.

Encouraging men to express intimate emotions and be vulnerable is a good step, but the problem can’t be solved without structural changes, he said.

“The socialization plays a really big role, but it’s not the entire picture,” he said. Placing more societal value on friendships instead of romantic relationships is another step, he said — as “institutions, workplaces, schools, ought to be thinking about ways they can help people cultivate healthy friendships.”

“My son, who’s almost 5 years old, he hugs his male friends all the time. They hold hands. At some point, he’s probably going to stop doing that. Probably because someone will make fun of him for doing that. And that makes me profoundly sad,” Cox said.

Classes like “Mighty Brotherhood,” offered by the nonprofit organization Mighty Writers, may be part of the long-term solution. The sessions are free for families, two parents told The 19th, and Williams said that to his knowledge, boys sign up after seeing social media or email blasts or hearing through word of mouth.

Ten boys joined the July 14 session, and seven participated in the following week’s discussion. Most were engaged, although a few had cameras off. They spoke to the others from their bedroom, the living room couch or the kitchen, several with family members nearby.

Angela Bostick said she’s noticed her son Roman, a high-performing student who enters eighth grade in the fall, become a more confident writer who’s better able to accept constructive criticism after sitting through the “Mighty Brotherhood” sessions.

“I’ve heard them on occasions, just riffing back and forth off of the support that they give one another,” she said. “I think hearing one Black man celebrate another Black man gives you space to do so as well. It invites you to give those roses while they’re there.”

Roman, 13, said over email, with permission from his mother, that the class had brought new emphasis to positivity and sharing. “Being a good man means being there,” he told The 19th. “For your family, friends, loved ones and anyone else, you become a good man if you look out for them, and make it so they know you care for them.”

Bostick, reflecting on her experiences raising a young Black man, said she appreciated that men of color are especially limited by society’s expectations of how men should act.

“There is a narrative that’s been there for all men in a lot of ways, but uniquely for men of color, that I think can be limiting,” Bostick said. “One of the more powerful ways to counteract that narrative is using your own voice.”

Williams said that after dispelling myths on masculinity for the boys in an early session, they were able to be authentically themselves.

In that session, he asked everyone to name some of the men that they respect — uncles, fathers or movie characters.

“I just told them, put that list away. Then I asked them, ‘Well according to society, what is a man?’ And on their list, they will put things like ‘You can’t cry. You have to be strong. You have to have a lot of money. You have to have a lot of girls. You can’t be emotional. You have to be ridiculously strong.’”

Then, Williams asked them to revisit the list of men they admire.

“I asked … ‘Do they have the things that you mention that society says that makes them a man?’ And they all, without any error, said ‘no.’”

The moment was a complete shift in the group, Williams said, “I think they were able to truly take the mask off and be themselves.”