ATLANTA — Senate Democrats, with their options limited in Washington, are in Atlanta on Monday to hold a rare field hearing they hope will draw public attention to restrictive voting bills proposed or enacted by Republican state legislatures.

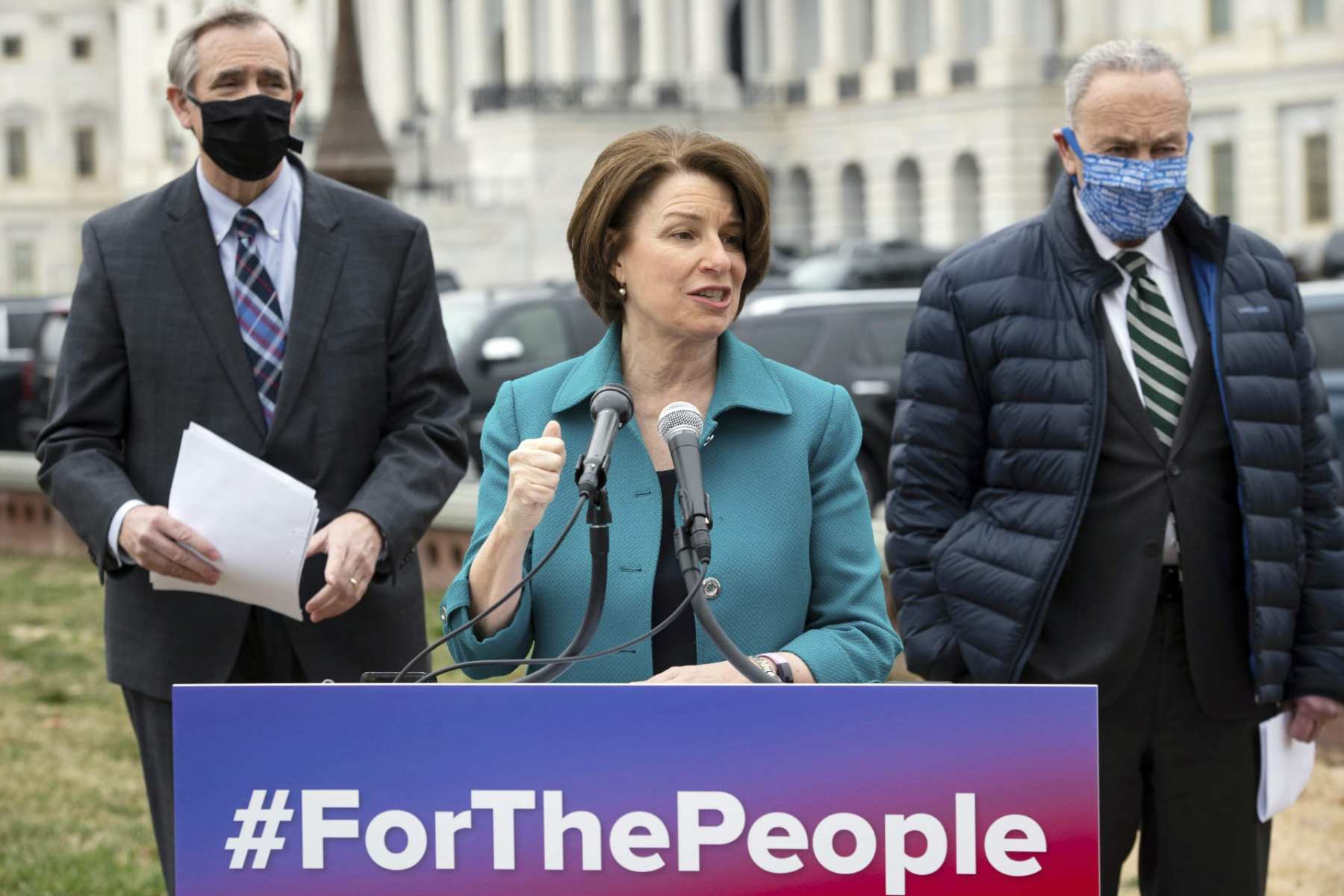

Amy Klobuchar, the Democratic head of the Senate Rules Committee, which oversees federal elections along with the chamber’s day-to-day procedures, said the panel decided to convene its first field hearing in more than 20 years in Georgia because its legislature passed an “egregious” restrictive voting law earlier this year.

“We cannot keep our heads in the ground, you’ve got to go out there and see exactly what’s happening,” Klobuchar told The 19th ahead of the hearing.

“There’s been over 400 bills introduced, 28 have passed and been signed into law, and one of them is right here in Georgia and it’s probably the most egregious example,” she added.

Georgia’s Republican-controlled legislature passed a bill in April that is expected to make it considerably more difficult for some of the state’s voters to cast ballots. The measure, which was quickly signed into law by Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, imposes additional identification requirements for absentee voters, limits the use of ballot drop boxes, curbs the authority of state and local election officials, and makes it a crime to offer voters food, or even water, while they are waiting in line.

The Republican effort followed record turnout in Georgia during the November 2020 elections, which resulted in Joe Biden’s historic win in a state that had not backed a Democratic presidential candidate since Bill Clinton in 1992. Then, Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff both won Senate seats in January runoff elections that handed their party control of the chamber. They are the first Democrats Georgia has elected to the Senate since 2000.

Warnock said at Monday’s hearing that the record turnout “should have been celebrated … instead, it was attacked by craven politicians more committed to the maintenance of their own power than they are to the strengthening and maintenance of our democracy.”

Former President Donald Trump has blamed his loss on unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud. In the days after the election, he criticized Georgia’s election officials and pressured them to “find” the votes he needed to win the state. Kemp, who initially drew the former president’s ire, told the New York Times earlier this year that Republicans “quickly began working” to “make it easier to vote and harder to cheat.”

Klobuchar rejected Kemp’s characterization of their effort. “They decided that instead of trying to fix their national policies or messages or candidates, that, after suffering a loss, they would respond by trying to disenfranchise people,” she said in an interview.

Warnock is also the first Black senator to be elected in Georgia, where the population is roughly 58 percent White and 40 percent Black. High turnout among the state’s Black voters was a driving force behind his and other Democratic wins. Witnesses at the hearing described how Georgia’s law will disproportionately impact communities of color in the state, which already contended with longer wait times at the polls. Critics of restrictive voting measures in Georgia and elsewhere say they are designed that way, in a throwback to the Jim Crow-era laws that made it difficult for Black voters to cast ballots and supported racial segregation.

Georgia voter José Segarra, an Air Force veteran, said that when he went to cast his ballot during the state’s early-voting period in October, it took two trips to the polls. He showed up on the first day with friends in their 70s, one of whom is a candidate for a knee replacement and another who has acute arthritis and uses a walker. They found a line snaking around their courthouse polling location. Unable to stand for what they anticipated would be an hours-long wait, they left. Serraga attempted again the next week with his wife and ended up waiting several hours.

“We were able to handle those three hours standing in line but we know that not everybody can,” Serraga testified. “This is wrong, it should not take so long to vote.”

Democratic Sen. Jeff Merkley, who is also on the rules panel, said he was “struck” by witness testimony that communities of color in Georgia had fewer voting locations and therefore faced longer lines. He said it sounded like a violation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The Supreme Court in 2013 struck down a key provision of the law that required areas with a history of discrimination to preclear changes to voting rules before implementation. The justices further weakened the statute in a ruling earlier this month. The erosion of the landmark civil rights statute has added to the urgency felt by Democrats and voting-rights advocates to counter the Republican push to pass voting restrictions.

Monday’s field hearing comes roughly a month after a sweeping bill to curtail the influence of money in politics and preserve voting access — known as H.R. 1, S. 1 or the For the People Act — failed to clear a procedural hurdle in the evenly split, 100-seat Senate, where nearly all legislation requires the support of 60 senators to proceed and Republicans are united in opposition.

The partisan battle over voting has also become enmeshed in another Democratic fight over whether they should change Senate rules to do away with the 60-vote filibuster threshold. The Democrats do not currently have enough support within their own caucus to change it.

Ahead of Monday’s hearing, Klobuchar, along with Merkley and voting-access advocate Stacey Abrams, held a roundtable with four Georgia voters who had difficulty casting ballots in the 2020 general election or Senate runoffs, before the state’s new restrictive law was in effect.

One was Keli Benford, a 21-year Air Force veteran who waited nearly seven hours to cast her ballot on the first day of early voting in October. Benford, who is Black, said on the hot day it was a “blessing” when someone brought water to those in line, she added. Under Georgia’s new law, the provision of water to a voter like Benford would be a criminal act.

Rules Committee Democratic Sens. Klobuchar, Merkley, Ossoff and Alex Padilla attended the hearing. None of the panel’s Republicans were there. Warnock and Democratic state Rep. Billy Mitchell read opening statements. Sworn witnesses were Segarra, along with a Democratic state Sen. Sally Harrell and Helen Butler, a former county elections official. Klobuchar said Republicans declined the opportunity to provide witnesses to defend Georgia’s law. Greater Georgia, a group founded by former Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler, who lost to Ossoff in the runoff, called the hearing “political theater.”

“Over the past year Georgia has become ground zero for the sweeping voter suppression efforts we’ve seen gain momentum all across our country,” Warnock said at the hearing.

“I want to be clear: Congress must take action on voting rights and we have no time to spare, there is nothing more important for us to do this Congress.”