Almost half of all the nation’s pregnancies are unintended. And a new government study suggests contraception access could play a meaningful role: Nearly a third of women who were sexually active but did not want to get pregnant were not using birth control.

The study, published Thursday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, analyzed data from 2017 to 2019, collected in 43 states, Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico. The data was collected through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a large CDC dataset collected through a randomized telephone survey.

About 60 percent of women ages 18 to 49, considered the years when someone is most likely to get pregnant, were deemed to have “potential or ongoing need for contraception.” That, per the CDC, means that they were sexually active with a male partner, were not pregnant and did not want to be pregnant. It also meant that neither the women nor their sexual partners had used “permanent contraception,” such as getting a vasectomy or having undergone tubal ligation. The researchers did not ask about people who did not identify as women but who also could become pregnant.

Of that group of women, almost a third — 30 percent — were not using any contraception as of their last sexual encounter. Another 30 percent were using less effective “barrier methods,” which include condoms, withdrawal, the rhythm method and the Plan B pill. In Puerto Rico, Texas and Hawaii, women were most likely to have used no method of contraception. (When used correctly, condoms are 98 percent effective and withdrawal 78 percent effective, which are less effective than other hormonal birth control.)

“Improving contraception access and uptake among these women might have a large effect on meeting reproductive health care needs and reducing unintended pregnancies,” the researchers wrote.

The paper does not offer insight into whether or how contraceptive use may have changed during the coronavirus pandemic, when many people delayed or were unable to access preventive health care.

Still, the authors argued that the paper could help health departments better address challenges in accessing birth control — illustrating reasons why people may not use contraception, and helping indicate the scope of the issue.

One barrier may be cost. Under the Affordable Care Act, health plans must cover every method of birth control without any out-of-pocket costs. But about a sixth of women — 6.2 million in total — who could benefit from contraceptive care did not have health insurance, the authors found.

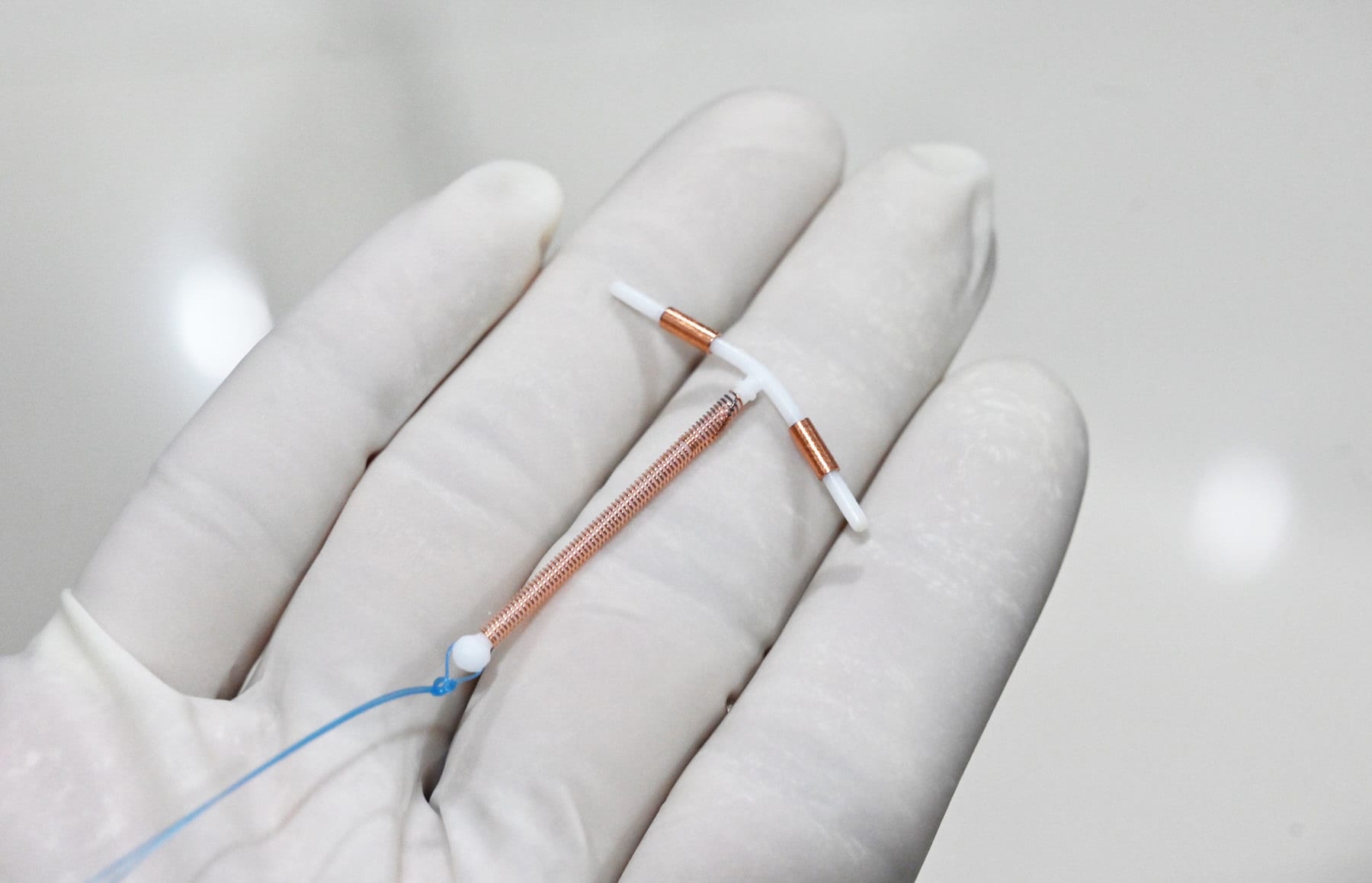

And birth control — particularly more effective methods such as intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants — can cost more than $1,000 without health insurance.

Some clinics will provide family planning services to low-income women at little to no cost, through the federal Title X program. But policies implemented by former President Donald Trump — meant to eliminate government funding for Planned Parenthood and other organizations that refer for abortion — dramatically limited that program’s reach. More than 1,000 family planning clinics, including 400 Planned Parenthood affiliates, lost Title X dollars under the last administration. In many parts of the country, Planned Parenthood is the only family planning provider. The Biden administration is still working to undo those regulations.

Still, cost is only one issue.

The health care infrastructure may not be fully equipped to provide birth control, or talk women through their options, the researchers suggested. Health care providers may not be comfortable or feel adequately trained to provide contraception. Some may not prescribe more effective methods because of lower payment rates from health insurance. Women may not know about services available to them. Local health departments may not have the data or infrastructure to understand how to do outreach, or to help connect people with family planning services.

“Ensuring access to contraceptive services is important to promote reproductive autonomy, prevent unintended pregnancies, and promote optimal and equitable reproductive health,” they wrote. “Understanding the need for contraceptive services, including the number of uninsured women who might need publicly supported care, can help jurisdictions plan health care delivery to support women and their partners in choosing whether and when to become pregnant.”

The researchers did not ask about or examine the role of side effects in determining whether or why women might not use birth control. But that may also play a role.

For some people, hormonal birth control can have mood-related side effects, research shows, especially in those with a history of depression. Some have also reported breast tenderness, weight gain and feelings of bloatedness. A 2013 CDC paper suggested that about 63 percent of women who had stopped using oral contraception did so because of side effects.