The U.S. Supreme Court is reentering the abortion debate this fall, hearing arguments over the constitutionality of a Mississippi law banning the procedure after 15 weeks of pregnancy. But though observers expect the court’s conservative majority to issue a ruling that could potentially scale back or even eliminate Roe v. Wade, the nation’s decades-old abortion rights guarantee, some states are moving forward with even tighter restrictions.

On September 1, a Texas law passed in May that effectively bans abortion after six weeks went into effect. The law directly violates Roe v. Wade, which guarantees the right to terminate a pregnancy up until the fetus can independently live outside the womb, usually around 23 weeks of pregnancy.

A six-week ban on abortion would be much more restrictive than it sounds, acting as a de facto ban for many. The 19th spoke to experts to understand just how restrictive these laws are, who would be most affected, and why, legally, their future is still unclear.

What does six weeks into a pregnancy look like?

For many people, six weeks is early enough that they haven’t actually realized they are pregnant.

Most abortions occur in the first trimester, and don’t require surgery. In 2018, the most recent year for which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has data, more than 92 percent of abortions took place at or by the 13th week. Almost 78 percent took place at or before nine weeks of pregnancy. That same year, about 36 percent of abortions — just over a third — were performed at or before six weeks.

That indicates that the majority of abortions occur between six and 13 weeks of gestation. A six-week ban would prohibit the procedure at a point when almost two-thirds of people who would have sought an abortion haven’t yet terminated their pregnancy, according to those numbers.

The pregnancy clock starts by counting back to the person’s last menstrual period. A typical menstrual cycle is 28 days — four weeks — but many people have irregular periods, which can be brought on or exacerbated by stress or fatigue. Those factors mean someone might not realize they are pregnant until 30 or 40 days, which is just shy of the six-week deadline. Some pregnancy tests can detect a positive before a missed period, but that isn’t the norm.

“To call it a six-week ban — it’s really a two-week window at best,” said Katherine Kraschel, a lecturer at Yale Law School and expert on reproductive health policy. “That would be if the pregnancy test was taken the day they missed their period, and assuming they have a four-week menstrual cycle.”

Six weeks is early enough that many people aren’t likely to realize they are pregnant, let alone decide whether they want to get an abortion.

No organization collects data tracking when most people discover they have conceived. But about half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned. And in those cases especially, people often don’t realize they are pregnant until they have missed at least one menstrual cycle.

“Some people have thought about abortion before, but not everybody,” said Elizabeth Nash, who tracks state policy for the nonpartisan Guttmacher Institute. “That means they need some time to figure out what they want to do — and these are the people who know they’re pregnant.”

What about other abortion restrictions?

States that have passed six-week bans all have other restrictions in place, which can make the deadline even harder to meet.

“This new law like the one Texas imposed is operating in a broader regulatory framework that makes it difficult to obtain abortion,” said Melissa Murray, a reproductive law expert and professor at New York University. “These laws don’t operate in isolation. They operate within a web of other restrictions.”

In Missouri, which passed its six-week ban in 2019, people must wait 72 hours — three full days — between the initial visit and the actual abortion. Ohio, which also passed a six-week ban that same year, has a 24-hour waiting period. Kentucky, Texas, South Carolina and Louisiana also enforce 24-hour waiting periods.

Beyond waiting periods, all of those same states have passed other laws that would more heavily regulate abortion providers, such as requiring that the procedure only be performed by physicians who have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, or dictating that the facilities providing abortions meet certain physical construction standards. Some have also prohibited insurance from covering abortion, which can cost upward of $400.

A study from Texas found that, when the state passed new restrictions on abortion providers, the regulatory burden drove almost half the state’s clinics to close down. The few providers that survived had to serve more patients — and those who were not near enough to an abortion facility were often unable to get pregnancies terminated. (Those restrictions were struck down by the Supreme Court, but only after many clinics had closed their doors.)

“The restrictions on providers have had a direct impact on the number of providers available in those states,” said Laurie Sobel, associate director of women’s health policy at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. “It’s a burden on both the provider and patient.”

That burden is most likely to affect people who already have a harder time accessing health care: people with lower incomes, those who live in rural areas, and those who may already have children.

Not only would they have a narrow window to discover their pregnancy and decide if they want an abortion, they would also need to figure out transportation, pull together money and arrange for child care. Those traveling further — in some cases, hundreds of miles — might also need to find some kind of overnight lodging.

“Those are all barriers for people to be able to obtain an abortion at any time. But if you make a time limit, they have to jump through all those hurdles even faster,” Sobel said.

Six-week bans have surged in the past three years. But what is their future?

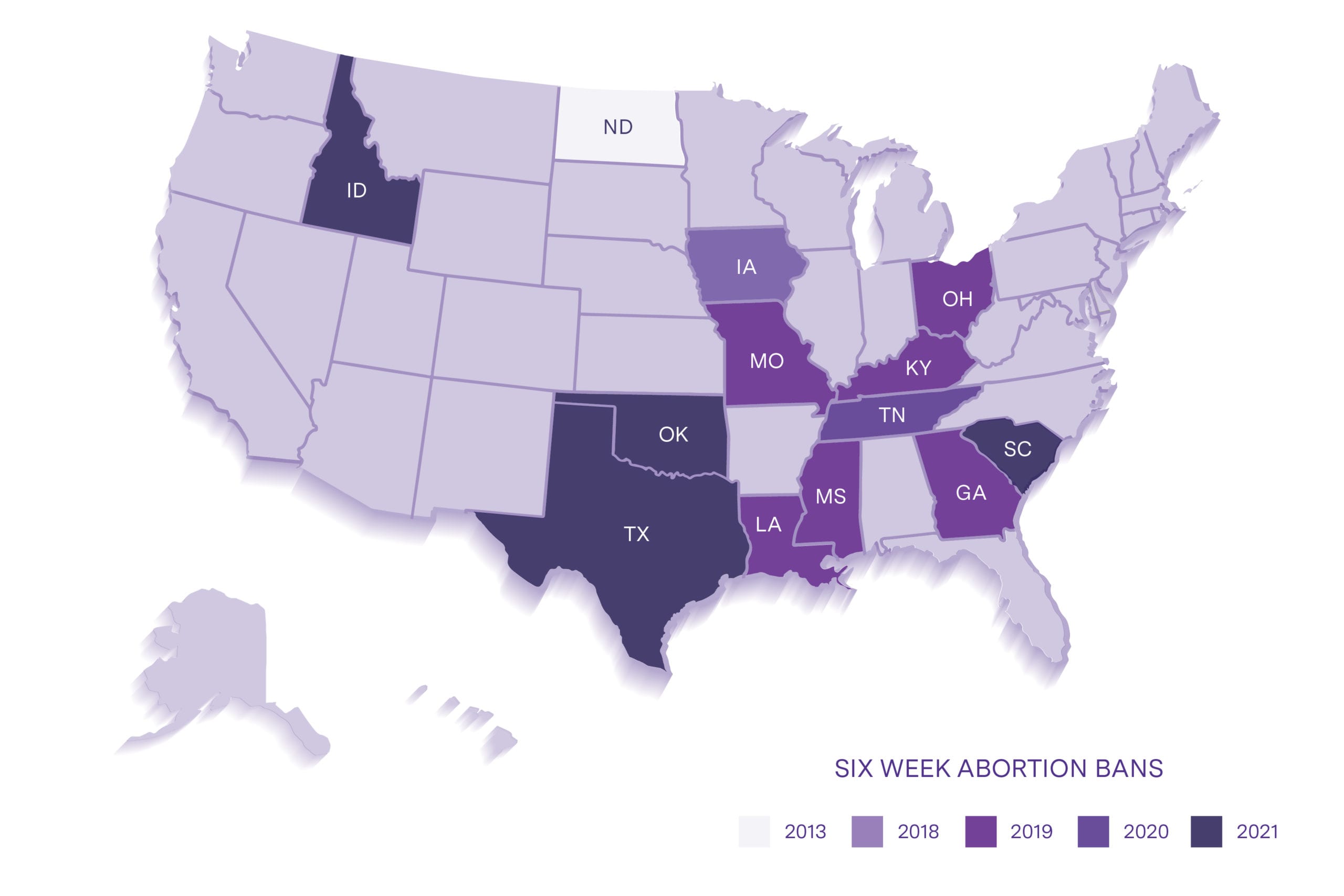

Just a decade ago, six-week abortion bans were relatively unheard of. In 2013, North Dakota became the first state to pass one, using legislation designed and promulgated by the conserative anti-abortion group Faith2Action.

No others were signed into law until 2018. But since then, they have spread through conservative states. Texas is the 13th state to have enacted a six-week ban.

The laws emerged in part, Nash said, because states passing six-week bans had already become so restrictive that this type of law was the logical next step for lawmakers looking to further limit abortion access.

Legal experts also attribute the surge to former President Donald Trump’s efforts to nominate Supreme Court justices who opposed abortion rights, and who were seen as likely to rule in favor of enhanced restrictions on the procedure. By 2019, Trump had successfully nominated two justices — Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh — who were viewed as unfriendly to abortion protections.

“They’ve said, ‘This is unconstitutional under Roe v. Wade, but we’re anxious to get to the Supreme Court. We think there’s a willingness to look at it again,’” Sobel said. “It’s not a hidden agenda. It’s there for everyone to see.”

Only three of the bans — those in Texas, Idaho and Oklahoma — have not been blocked by either a lower federal court or a state supreme court. (Idaho and Oklahoma’s laws haven’t yet taken effect.)

The Texas law still faces legal challenges, but the Supreme Court did not respond to a request to block the abortion ban or require lower courts to go forward with the appeals process before it went into effect. Under the existing Roe v. Wade precedent, it’s difficult to see how the bans could stay intact, since six weeks is well before the threshold of fetal viability.

And while the Supreme Court is famously unpredictable, the justices — depending on how they rule on Mississippi’s ban — could create a new precedent that allows for six-week bans, or that opens the door to future favorable rulings on these types of restrictions.

“’We’re always in this position,” Nash said. “We don’t know what the court is going to do, but it seems like they have a number of roads they could go down.”