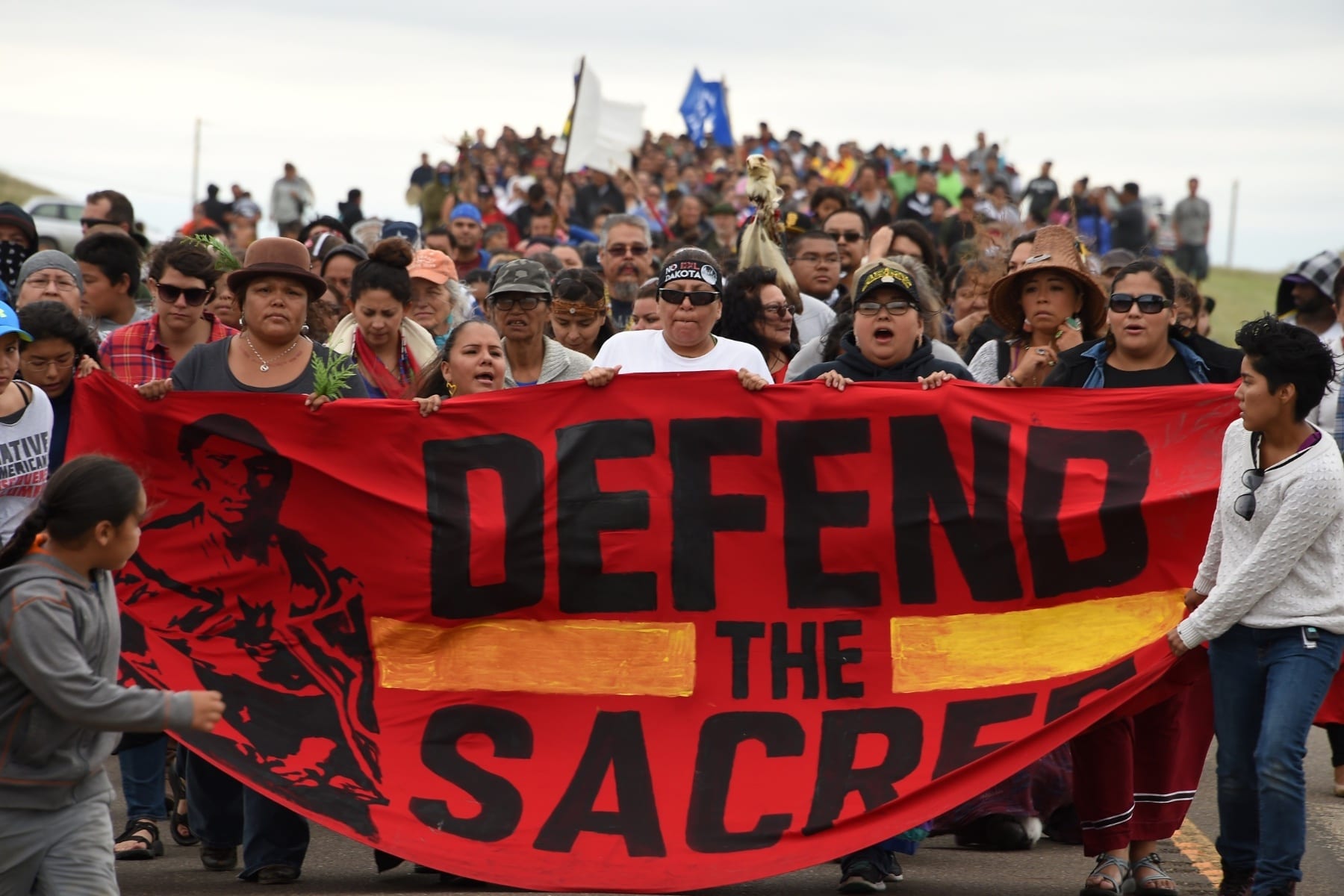

Indigenous women and LGBTQ+ people, from grassroots activists to leaders in tribal governments, led protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in 2016. For many advocates, it was the first time they watched a movement that was led largely by women and queer folks around a unifying cause that was not based on gender.

“It was incredibly powerful,” said Michelle Cook, an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation and Arizona-based human rights lawyer who was at the pipeline protests that began five years ago last month.

The protests at Standing Rock — the North Dakota reservation where activists camped from April 2016 to February 2017 — regularly turned violent, with law enforcement using tear gas and deploying security dogs against protesters. It captured the media’s attention for the summer and fall, but the work of the women and LGBTQ+ people on the ground at Standing Rock didn’t stop when the protesters — and cameras — left Standing Rock.

Advocates like Cook saw a potential ally in President Joe Biden, who on the campaign trail promised to help improve relations with tribal nations and tackle environmental issues. Those two issues were central to the protests over the pipeline in 2016: Indigenous leaders and environmental activists argued that the pipeline would jeopardize water supplies for the Oglala Lakota, Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes and disturb nearby sacred native sites.

But last month, the Biden administration said it would not shut down pipeline activity while it undergoes a court-ordered environmental review. Indigenous leaders had hoped that the administration would use the January court ruling as an opportunity to, at the very least, pause pipeline operations, if not stop them completely. They argued that because the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia did not revive a key pipeline easement, upholding the decision of a lower court, the pipeline is operating illegally, violating the National Environmental Policy Act.

Earlier this month, the Biden administration once again said that it would not pause pipeline activity during the court-mandated environmental review. The $3.8 million underground pipeline, which was completed in 2017, is nearly 1,200 miles long and transports crude oil through North and South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois.

Now, five years after these protests began, Indigenous women and queer activists are reflecting on the movement catalyzed by Standing Rock.

“I think what was very unique about what occurred at Standing Rock was how it was led by women,” Cook said. “That purity, that desire to protect the water and to protect the land. I think that is why it’s so important; they’re there to protect their family and their children. So their leadership and their motivation for making those choices is an act of love.”

YoNasDa Lonewolf, an Atlanta-based activist who protested at Standing Rock from September 2016 to January 2017, echoed that sentiment.

“We are the caretakers,” Lonewolf, a member of the Oglala Lakota, said. “We are the ones that give life and have a connection to this Earth — to the heartbeat of Mother Earth. We feel that she’s screaming and yelling, so I think that especially in Standing Rock, that’s the reason why so many women went to the front.”

Indigenous queer activists also felt called to join the fight for sovereignty and clean water. Layha Spoonhunter, a Wyoming resident and member of the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes, spent four months at Standing Rock in 2016. He was stationed primarily at the two-spirit camp and said protesting against the DAPL created a sense of community among those with marginalized identities, like him.

This is especially true for Indigenous two-spirit people, who often feel unrecognized by their tribal communities for their gender or sexual identity, even though they have always been revered for their ability to maintain balance in tribal structures, Spoonhunter said.

“Standing Rock was a chance to go back to our own roots in terms of gender and sexuality,” he said. “Being at Standing Rock and being around LGBT youth who, for maybe the first time, weren’t afraid to express themselves and be in this community where you were actually welcomed, was a huge difference.”

Without intervention from the Biden administration, Indigenous people said they now face an uncertain future without help from a president that they helped deliver key battleground states for.

Indigenous peoples played a part in helping Biden win states like Wisconsin, where tribes like the Menominee Nation in Menominee County cast the highest vote share of any county in the state. In New Mexico, Biden won counties like McKinley, where the population is roughly 80 percent Indigenous people.

“We pushed for Indigenous votes because President Biden said no oil pipeline,” Lonewolf said. “Now he wants to listen to big business and big companies.”

Now, these activists are thinking critically about next steps.

Cook, who is a founding member of the Water Protector Legal Collective, is crowdfunding money for defense against Energy Transfer LP –– the company developing the pipeline, which has filed lawsuits over access to records and legal documents collected by on-the-ground counsel during the protests.

They’re also turning their attention to healing from the PTSD caused by protesting the pipeline, which Lonewolf and Spoonhunter both said they struggle with. Indigenous people in America already experience higher rates of psychological distress.

Still, even as they are healing, they are ready for the fight against DAPL to continue.

“One thing I’ve always told Native youth is: the day we’re born, we’re born fighters,” Spoonhunter said.

He added, “It’s a battle, it’s a battle for your life.”