Editor’s note: This article has been updated to include the 2024 and 2025 quarters.

The United States Mint has announced the final round of women to be featured on the nation’s currency through the American Women Quarters Program. The 2025 quarters will feature Ida B. Wells, Juliette Gordon Low, Dr. Vera Rubin, Stacey Park Milbern and Althea Gibson.

Designs have not yet been released for the last five quarters.

Melanie A. Adams, the interim director at the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum, told The 19th in an email that the program sought to highlight women from ethnically, racially and geographically diverse backgrounds. “A central focus of the American Women’s Quarters program was including women whose stories could be considered ‘untold’ to the general public,” she said. “It’s been encouraging to see people engage with history that’s both new to them and in a new format through a physical quarter.”

The program began in 2022 as a result of legislation introduced by Rep. Barbara Lee, a California Democrat.

“I wanted to make sure that women would be honored, and their images and names be lifted up on our coins. I mean, it’s outrageous that we haven’t,” Lee said when the program was first unveiled in 2021. “Hopefully the public really delves into who these women were, because these women have made such a contribution to our country in so many ways.”

Lee began drafting legislation on the coin program with help from Rosa Rios, the Treasury official who oversaw the United States Mint under former President Barack Obama. She introduced her bill, the Circulating Collectible Coin Redesign Act, with two Republicans, Reps. Anthony Gonzalez of Ohio and Deb Fischer of Nebraska. It was signed into law in 2020.

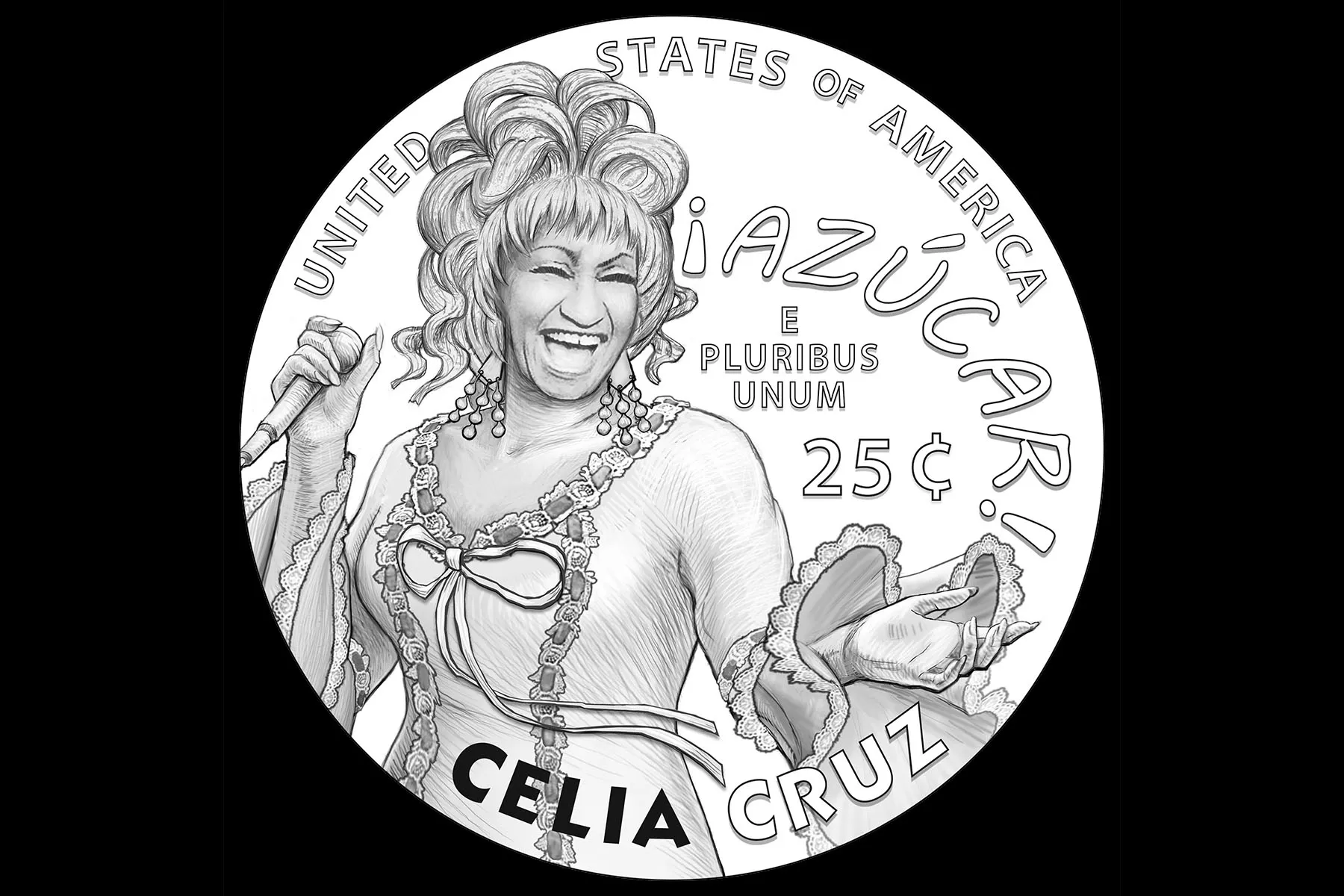

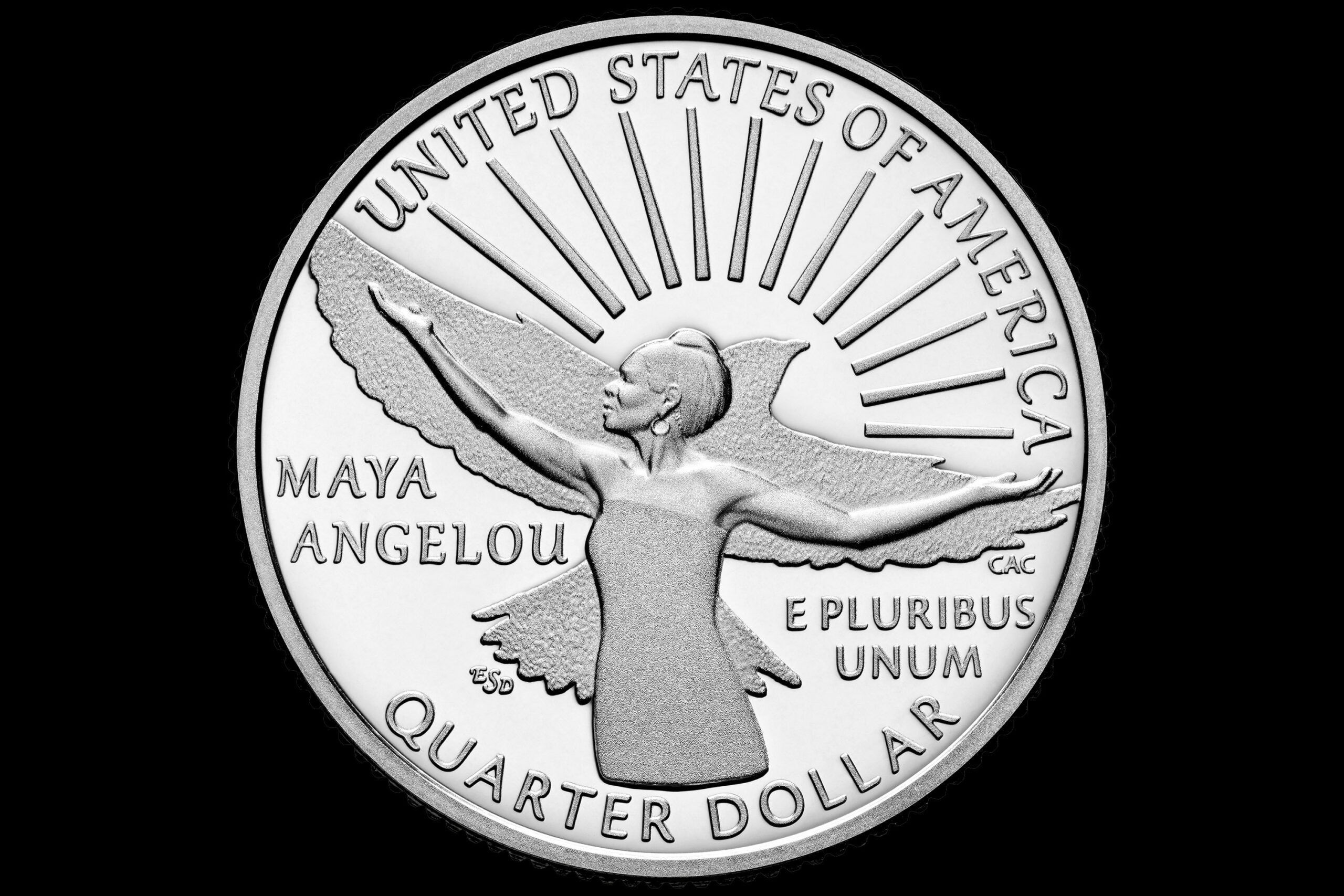

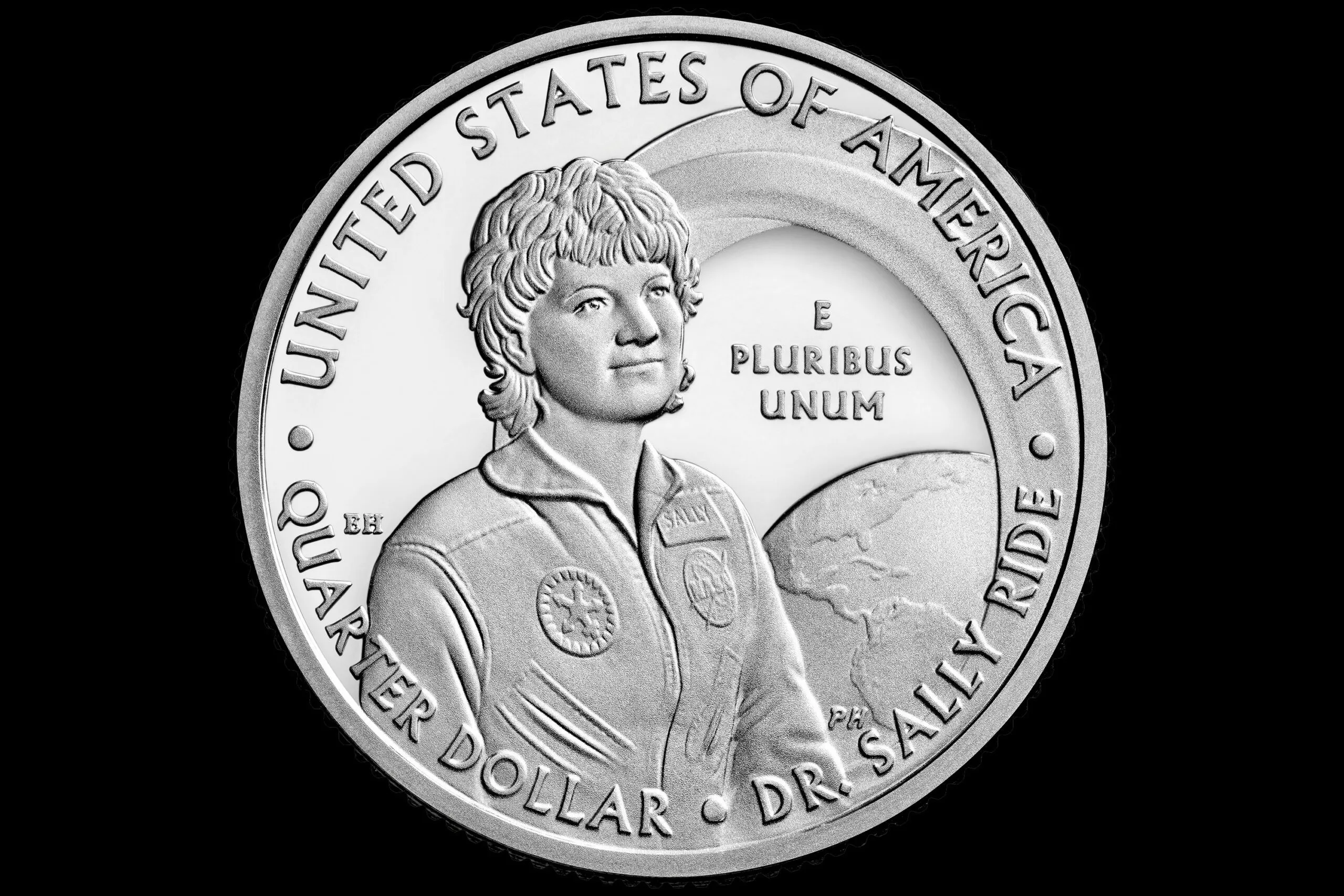

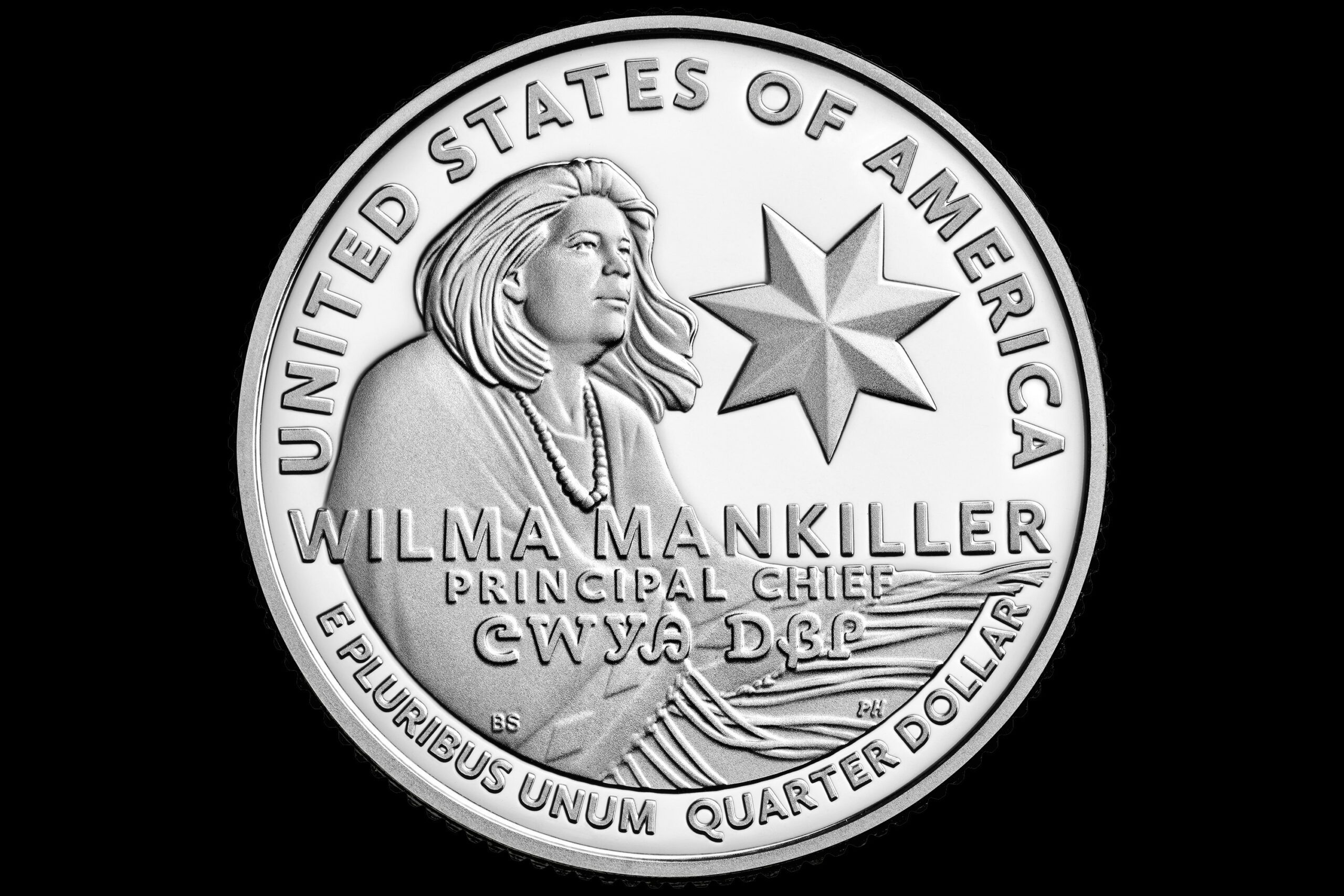

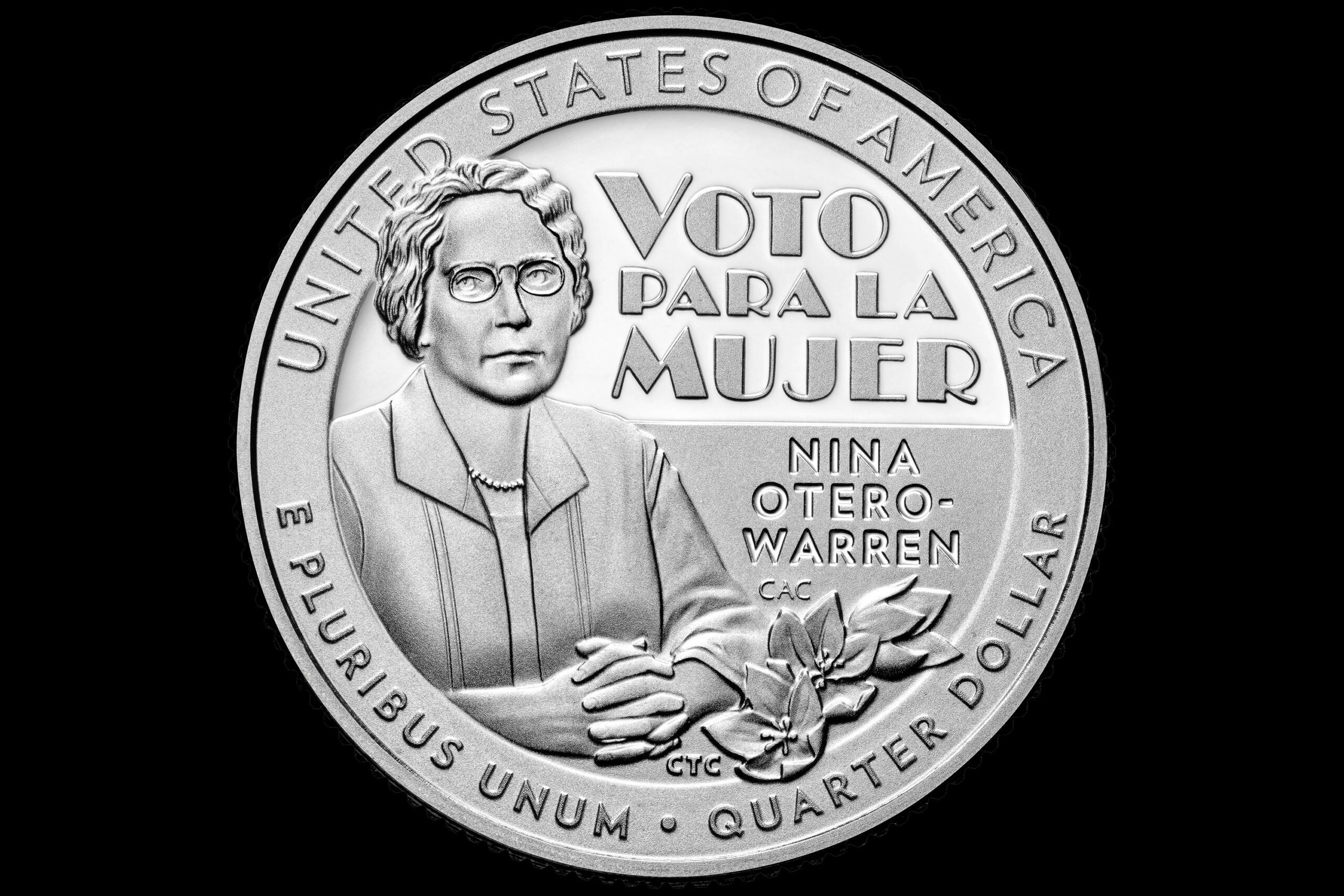

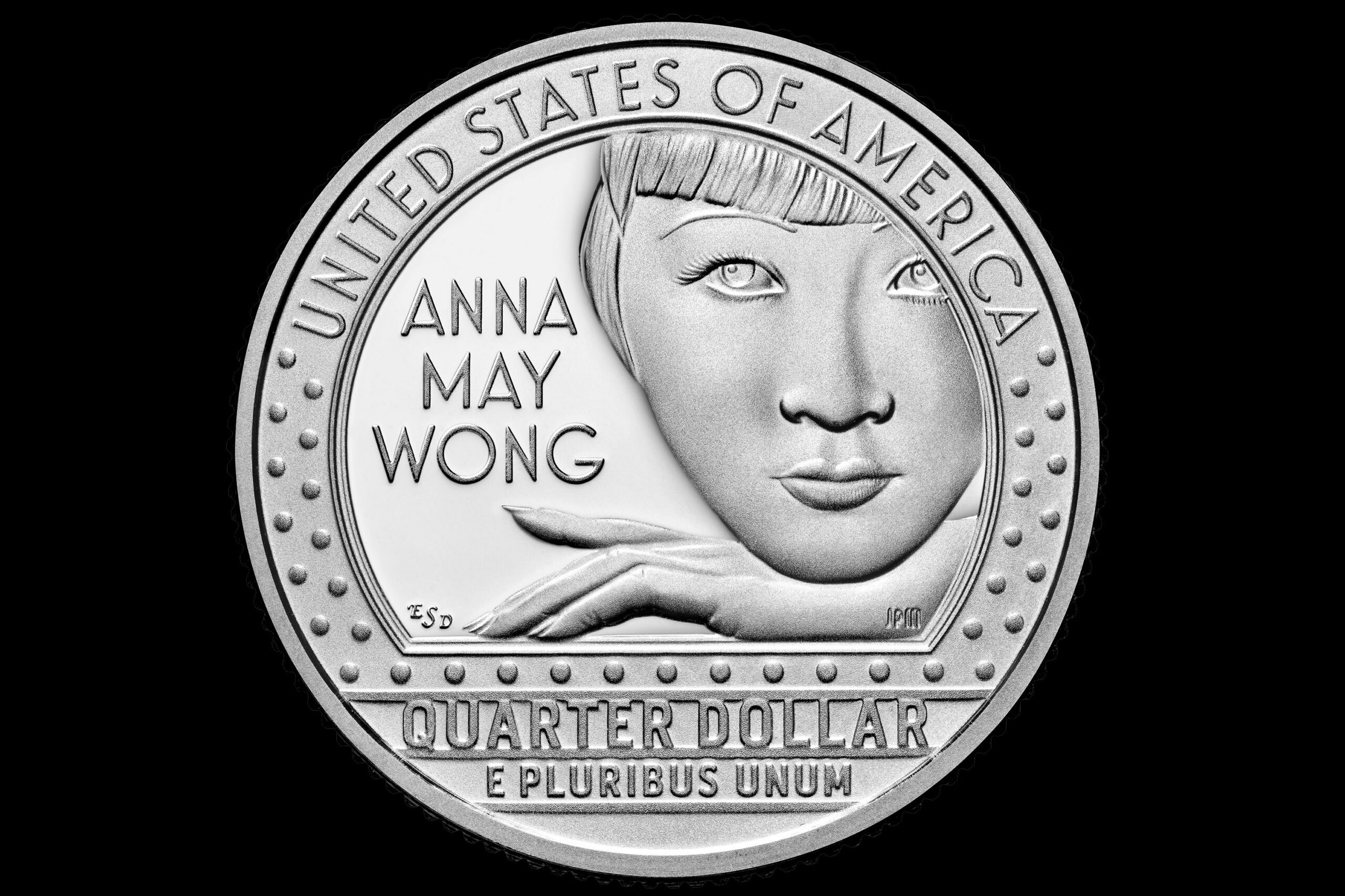

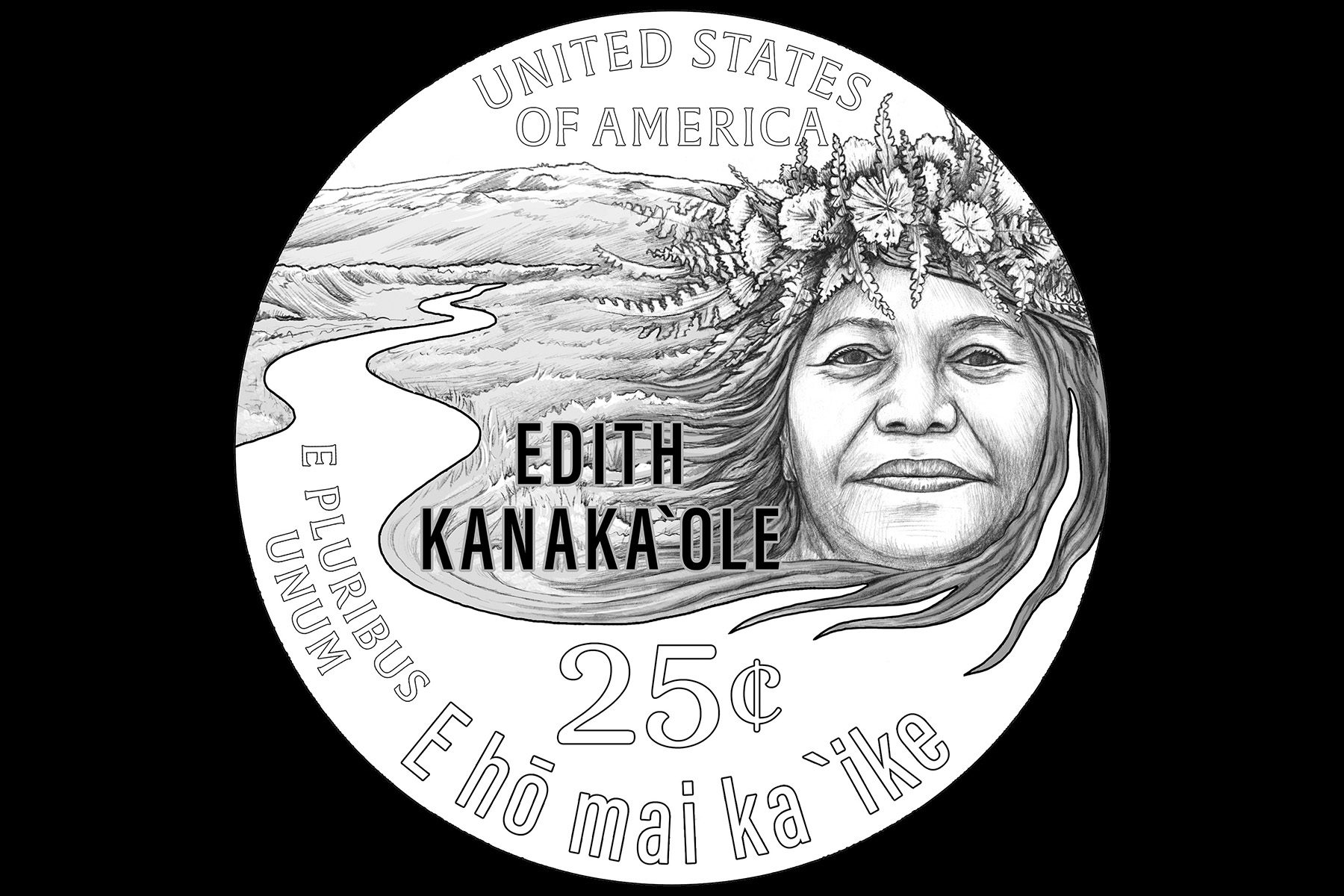

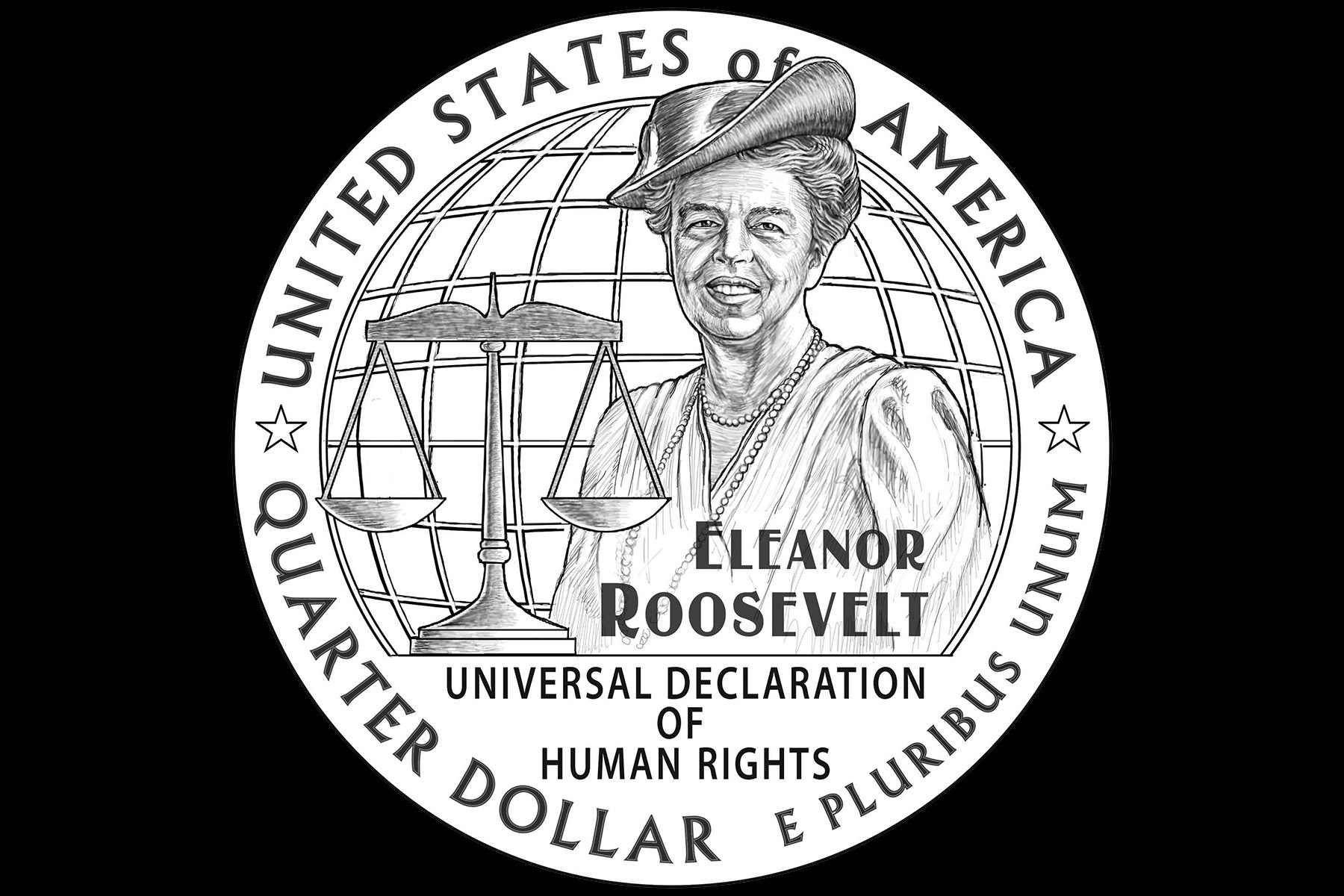

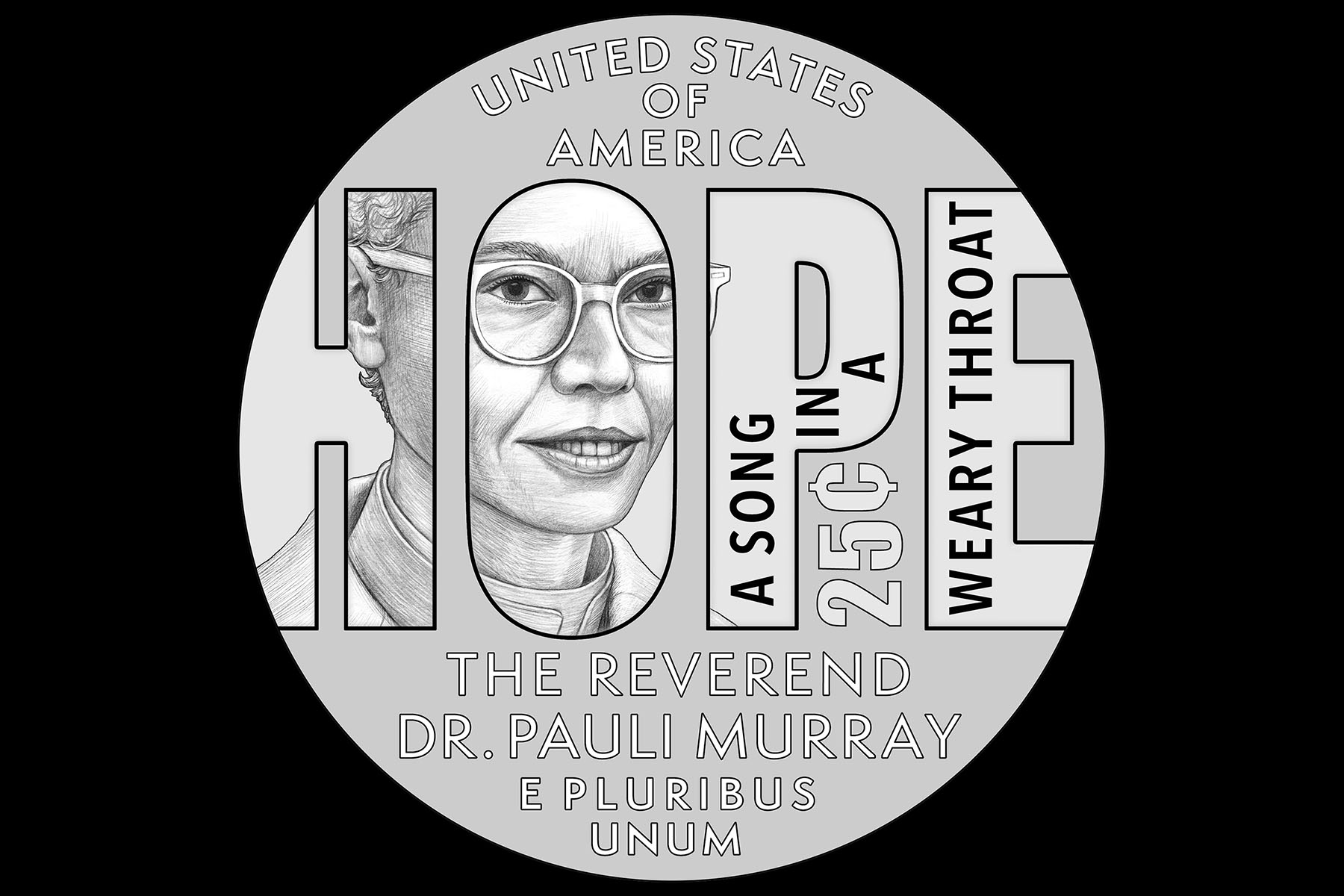

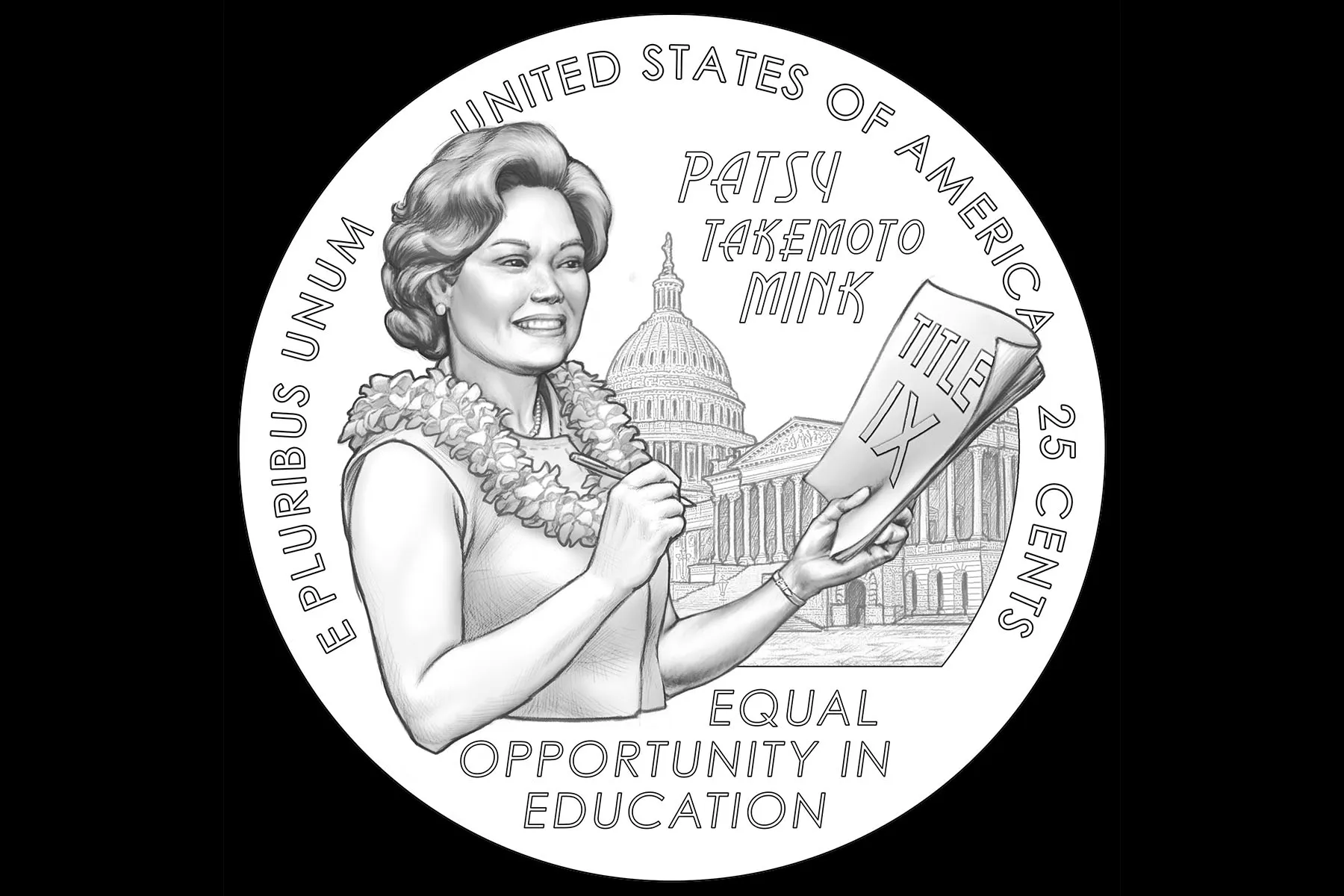

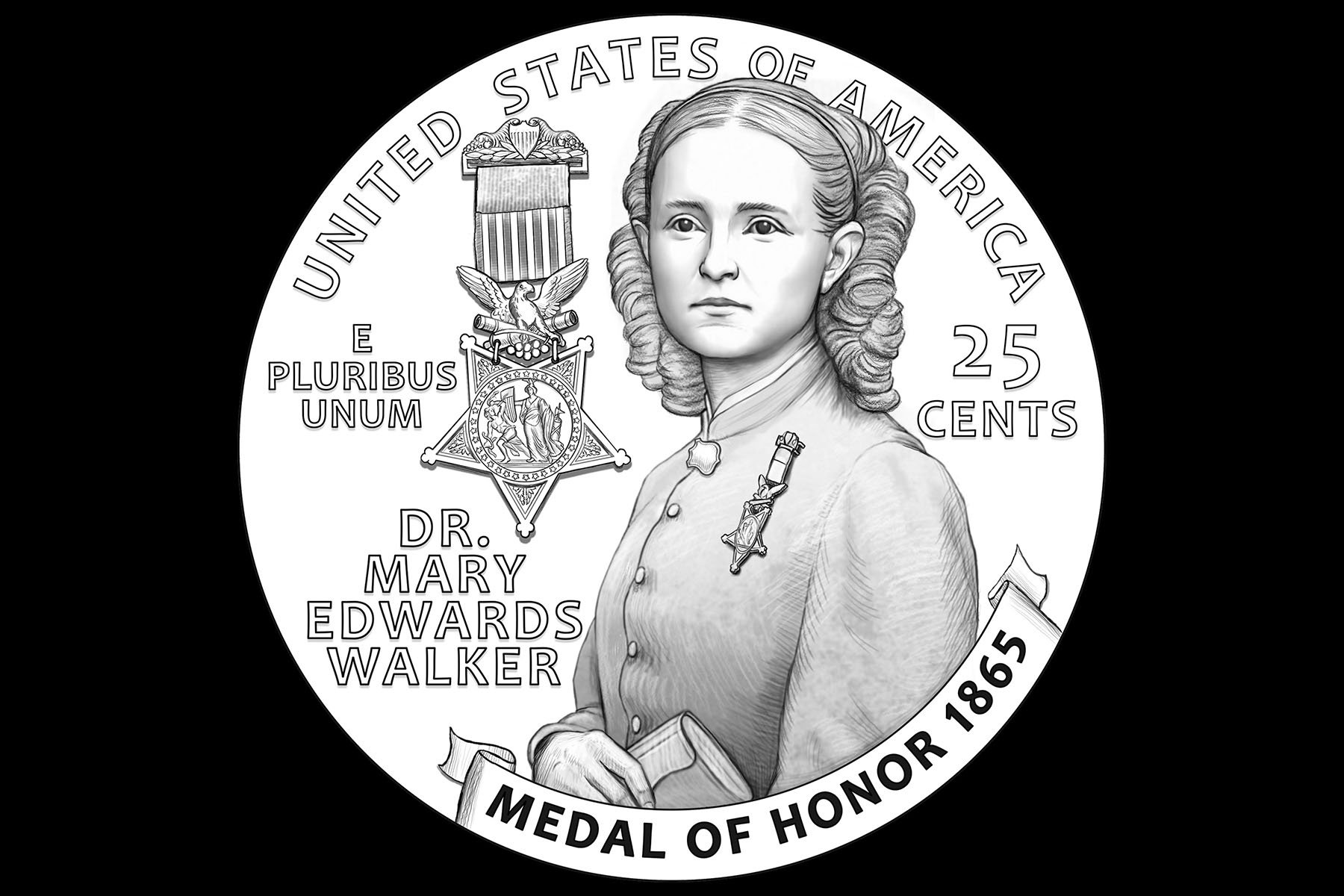

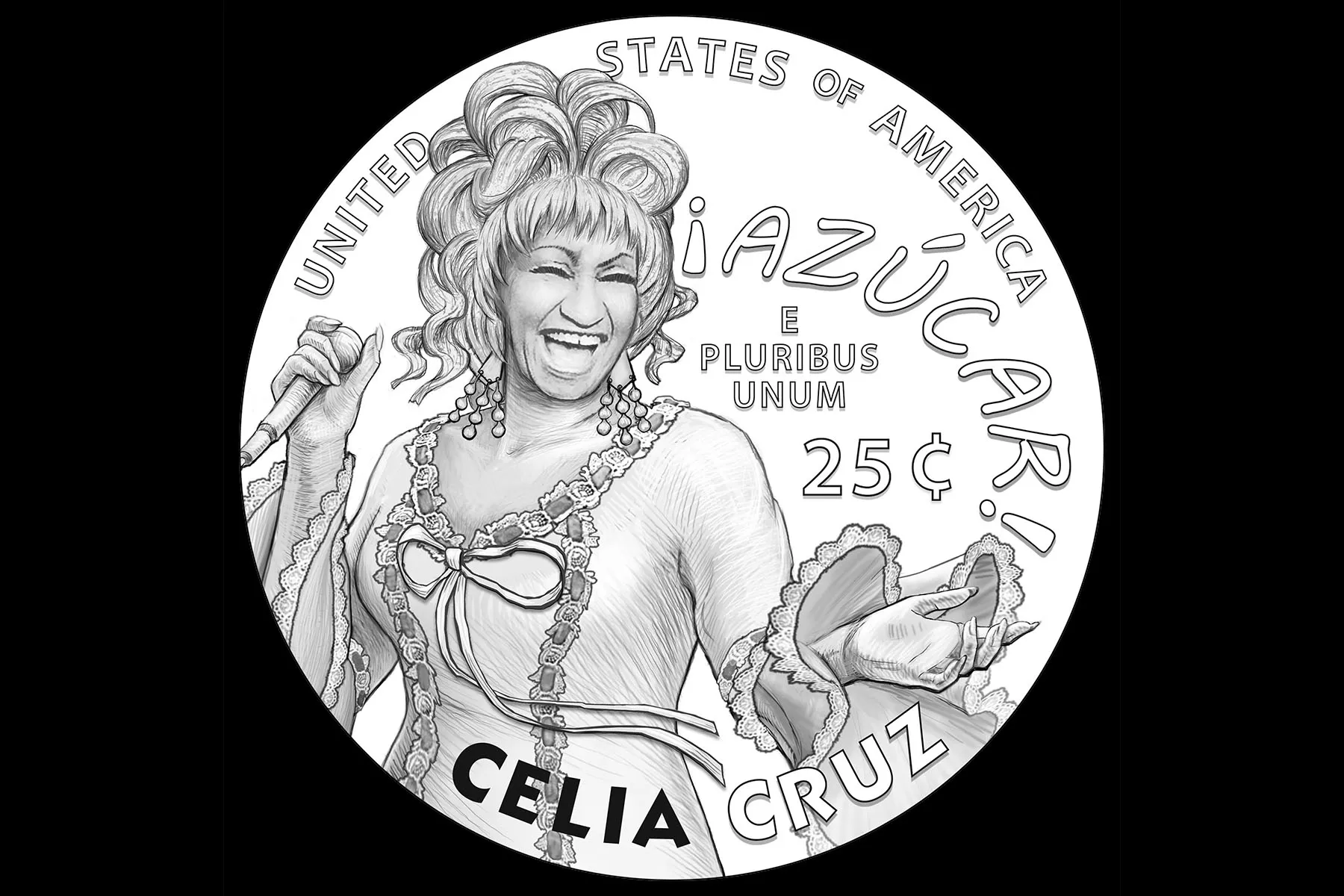

The program has had the United States Mint circulate up to five chosen women on the reverse (tail) side of the quarter-dollar, allowing for up to 20 women to have their faces on U.S. quarters by the end of 2025. The Mint selected the first five women to be in circulation in 2022: the civil rights activist and poet Maya Angelou, astronaut Dr. Sally Ride, suffrage leader and educator Adelina Otero-Warren, actress Anna May Wong, and activist and Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation Wilma Mankiller. The women honored in 2023 were the pilot Bessie Coleman, the Indigenous Hawaiian dancer Edith Kanaka‘ole, the former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the journalist Jovita Idar and the ballerina Maria Tallchief. Quarters issued in 2024 will honor the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray, Patsy Takemoto Mink, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, Celia Cruz and Zitkala-Ša.

“ We could easily do this program for the next 20 years and not even scratch the surface of honoring every woman who has had a significant impact on our Nation’s history,” Brent Thacker, a spokesman for the U.S. Mint, told The 19th in response to e-mailed questions.

It’s not just about the coins, but about what they represent and the power they have to start a dialogue around women who were trailblazers in their fields, Lee said.

The public had the opportunity to nominate women for the quarters using a Google form established by the National Women’s History Museum. Janet Yellen, the Treasury secretary, selected the women in consultation with the Smithsonian Institution’s American Women’s History Initiative, the National Women’s History Museum and the Congressional Bipartisan Women’s Caucus. With this public form and additional input from organizations, Lee had hoped to highlight a diverse range of women who come from all walks of life.

The women chosen had to be deceased and could be influential in a myriad of fields and time periods including, but not limited to, civil rights, the women’s suffrage movement, government, the humanities or science.

Lee said she hoped opening the process to the public allowed young people to learn about influential women in history and understand their stories before submitting nominations.

“I think it is a good organizing tool that communities should use, and have children kind of tell stories and do the research and come up with who they think would be the woman that should be submitted,” Lee said. “It’s about time that people who exchange currency and coins understand that women deserve things. This is long past due.”

Adams said the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum established new connections with communities as part of its selection process and that it hoped to build on that. “We consider efforts relating to our American Women Quarters program as just the start of what will hopefully be a wide-ranging and extended relationship.”

The women on the faces of the quarters

Maya Angelou (April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014)

Angelou was a civil rights activist, poet and author of the critically-acclaimed 1969 memoir “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” She wrote the book, which documents her childhood in Arkansas and her experiences of racism as a young Black woman, following her efforts to aid Black leaders across the nation, including Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. In 1993, she became the first woman poet to speak at a presidential inauguration in U.S. history, reciting “On the Pulse of Morning” during former President Bill Clinton’s ceremony. She wrote seven autobiographies, three essay collections and many other pieces that were adapted for the screen over the years. “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you,” Angelou said.

Dr. Sally Ride (May 26, 1951 – July 23, 2012)

Ride became the first American woman — and youngest American — to fly in space on June 18, 1983, on the Challenger space shuttle after NASA changed its policy to allow women astronauts in space in the late 1970s. Ride was studying physics and English at Stanford University when she saw her student newspaper run an ad looking for astronauts. She applied right away and was one of just six women selected to train. In 1986, when the Challenger shuttle exploded, killing all on board, Ride was one of the top investigators looking into the tragedy. In 2001, Ride co-founded Sally Ride Science, which aimed to motivate primarily young women and girls to explore the science and space fields largely dominated by men.

Wilma Mankiller (November 18, 1945 – April 6, 2010)

Mankiller was the first woman to be principal chief of the Cherokee Nation and the first woman elected as chief of a major tribe. She dedicated her life to fighting for the rights of Indigenous people. Her activism began in 1969 through her support of a group of American Indians who took over the federal penitentiary on Alcatraz Island on San Francisco Bay to expose the suffering of Indigenous people in America. She became the director of Oakland’s Native American Youth Center and later founded the Community Development Department for the Cherokee Nation, where she worked to improve access to water and housing.

Adelina Otero-Warren (October 23, 1881 – January 3, 1965)

Otero-Warren was a leader in New Mexico’s women’s suffrage movement and the first woman to be superintendent of public schools in Santa Fe. Within the suffrage movement, she fought to include Spanish to reach more Hispanic women, and emphasized the need to publish suffrage material in both Spanish and English, making the movement more accessible. She also led the effort to ratify the 19th amendment in New Mexico. She worked tirelessly to include bicultural education in New Mexico and honor the cultural practices of the state’s Indigenous communities. In 1917, she was appointed as superintendent of public schools in Santa Fe, where she focused on promoting adult education programs and improving the physical conditions of schools.

Anna May Wong (January 3, 1905 – February 3, 1961)

Wong was the first Chinese American film star in Hollywood and appeared in over 60 movies, as well as starring in roles on television and on the stage. Growing up, she worked in her family’s laundry business while attending Chinese language classes after school. But when the film industry moved from New York City to California, she started visiting movie sets and was cast in her first starring role in “The Toll of the Sea” in 1922. After working in the United States for years, Wong moved abroad because of the discrimination she experienced in the American film industry. Later in her life, she became an activist, raising money and advocating for Chinese refugees during World War II. She was the first Asian American to lead a US television show, “The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong.”

Bessie Coleman (January 26, 1892 – April 30, 1926)

Coleman was the first African-American woman and the first Indigenous woman to hold a pilot’s license. She was also the first African-American person to hold an international pilot’s license. Coleman was one of 13 children born to George and Susan Coleman in Atlanta, Texas. Growing up, she helped her mother pick cotton and wash laundry to earn money. Inspired by her brother’s teasing upon his return from France in WWI, where he saw women flying planes, and incensed by the discrimination she faced in the United States, Coleman began learning French and applied to flight school in France. After earning her license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, she went on to purchase her own plane. She traveled throughout the United States and Europe, performing her famous tricks in flight shows, giving flight lessons and speaking to crowds. Coleman was known to stand up for her beliefs, often refusing to speak or perform in segregated spaces.

Edith Kanakaʻole (October 30, 1913 – October 3, 1979)

Kanaka‘ole was an Indigenous Hawaiian dancer, composer, professor and keeper of Indigenous Hawaiian culture. She helped to preserve those traditions by passing down the teachings of hula and Hawaiian chants. Her music won best traditional album awards at the premier music awards in Hawaii, and she gave an acceptance speech entirely in the Hawaiian language. During her time as a college professor, she developed courses such as ethnobotany, Polynesian history, genealogy and Hawaiian chant and mythology. A building at the University of Hawaii at Hilo bears her name. Kanaka‘ole also founded her own hula school and assisted in the development of the first Hawaiian language program for public school students.

Eleanor Roosevelt (October 11, 1884 — November 7, 1962)

Along with her duties as the longest-serving first lady, Roosevelt was an advocate for human rights, an author and a leader within the United Nations. She was instrumental in creating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Before her husband took office, she volunteered during World War I with the American Red Cross and in Navy hospitals. She was active in the Democratic Party and a volunteer teacher for immigrant children. Later, from the White House, she encouraged her husband to appoint more women to federal positions, held press conferences for women reporters, and supported government-funded programs for artists and writers.

Jovita Idár (September 7, 1885 – June 15, 1946)

Idár was a journalist and activist. She spoke out about racism against Mexican Americans, advocated for women’s suffrage and wrote articles in support of the revolution in Mexico. Idár and her family organized the First Mexican Congress in Laredo, Texas, to unify Mexicans across the border. She also started La Liga Feminil Mexicaista, a feminist organization that sought to empower women and provided education for Mexican-American students. Idár was active in the Democratic Party in Texas and nursed the injured across the border during the Mexican Revolution, which lasted through much of the 1910s. One of her chief causes was education, and she started a free kindergarten for children in her community.

Maria Tallchief (January 24, 1925 – April 11, 2013)

Tallchief was the first American prima ballerina. She was of Indigenous heritage, of the Osage Nation. Born in Fairfax, Oklahoma, she moved to New York City at 17 years old to pursue her dance career. After standing in as an understudy in the Ballet Russe, her career began to take off. Despite pressure to change her name for fear of discrimination, she continued to perform under the name Maria Tallchief. She later became the first American to dance with the Paris Opera Ballet and the first American to perform at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. Tallchief’s most famous roles were in “The Firebird” and “The Nutcracker.” She eventually started her own ballet school and dance company.

The Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray (November 20, 1910 – July 1, 1985)

Murray fought tirelessly for the rights of women and people of color, with a special emphasis on fighting “Jane Crow” — institutional discrimination against Black women. Murray’s essays and books, particularly “States’ Laws on Race and Color,” laid the groundwork for civil rights victories such as Brown v. Board of Education. They worked with leaders of the civil rights movement and helped establish the National Organization for Women, but felt neither group truly valued the work of Black women. In 1977, Murray broke further ground, becoming the first Black woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Patsy Takemoto Mink (December 6, 1927 – September 8, 2002)

Mink became the first Asian-American woman and woman of color elected to Congress when she won her seat in 1964. She faced race-based housing discrimination as a student and gender-based discrimination when she applied to medical schools — two experiences that she said shaped her politics for years to come. She pursued law instead and became the first Japanese-American woman to practice law in Hawaii. As a lawmaker, Mink sponsored some of the nation’s first child care bills. Her most famous legislative achievement is Title IX, which bars gender discrimination in education. The law was renamed in her honor after her death.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker (November 26, 1832 – February 21, 1919)

Walker, a Civil War surgeon, remains the only woman recipient of the Medal of Honor — the nation’s highest military decoration. Walker, one of few American women doctors at the time, volunteered as a medical worker on the front lines and eventually received official permission to work as an Army surgeon in 1863. President Andrew Johnson awarded her the Medal of Honor, but it was rescinded in 1917 because she was a civilian. She wore it for the rest of her life, and President Jimmy Carter restored the honor in 1977. Walker was also an advocate for women’s rights, supporting the suffrage movement and wearing pants in public — despite repeated arrests for doing so — for the rest of her life.

Celia Cruz (October 21, 1925 – July 16, 2003)

Cruz, known as the “Queen of Salsa,” introduced millions of listeners to Afro-Cuban music over her decades-long career. She toured the region with La Sonora Matancera, Cuba’s most popular band in the 1950s, as their lead singer and entered exile with them in the early years of Fidel Castro’s regime. Her performances, collaborations and costumes made her one of the most popular Latin artists in the world, and one of the recognized Afro-Latinas. Cruz recorded more than 80 albums and songs, and over the years she won four Grammys, three Latin Grammys and a posthumous Lifetime Achievement Award from the Recording Academy.

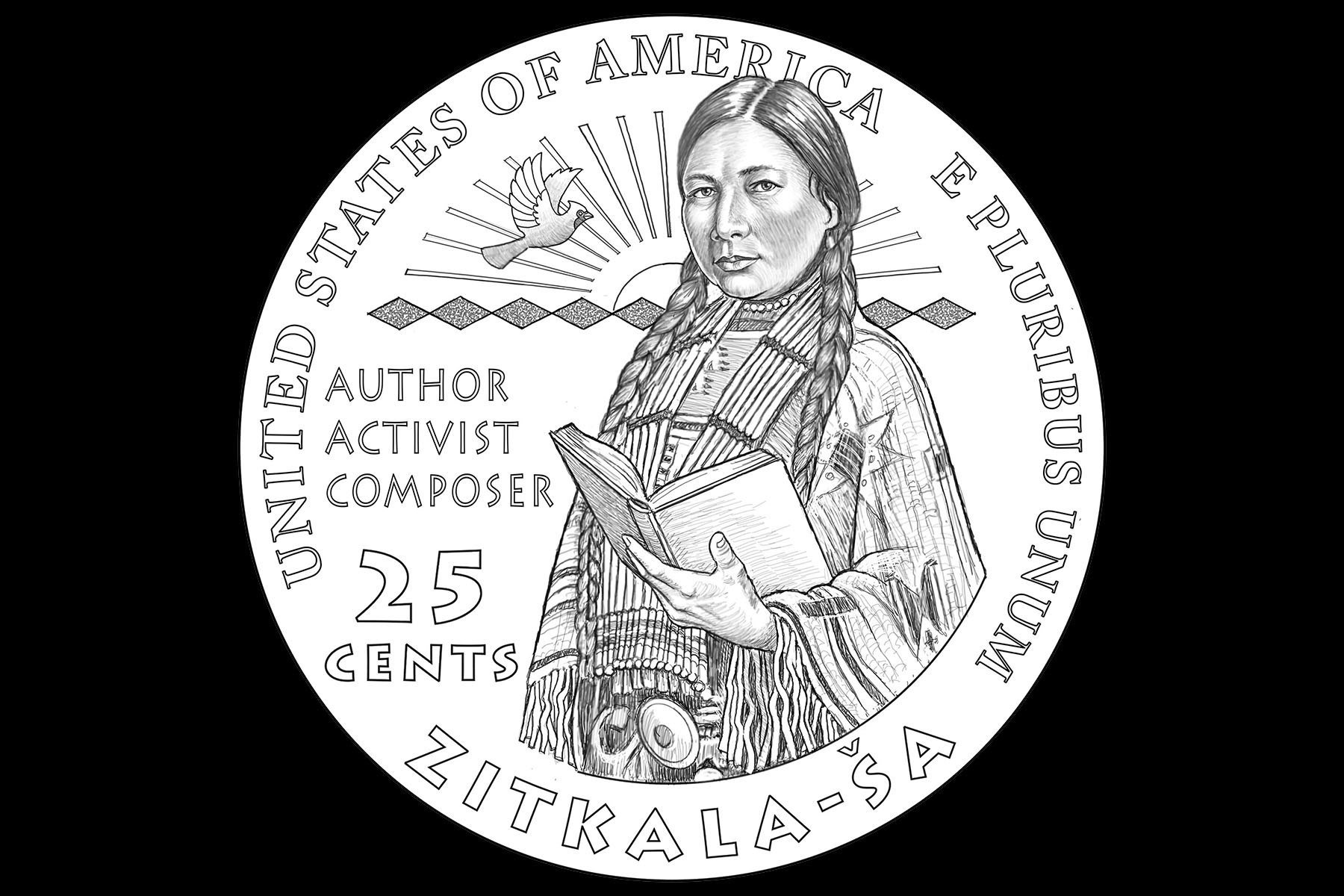

Zitkala-Ša (February 22, 1876 – January 26, 1928)

Zitkala-Ša, also known as Red Bird or Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, devoted her life to the rights of Indigenous people. She was born on the Yankton Indian Reservation and attended a White-run boarding school. Zitkala-Ša collected and wrote stories about Native American life, helping reshape perceptions of Native Americans that had fueled assimilation-based policies. She founded the National Council of American Indians in 1926 to further pursue efforts such as United States citizenship and self-governance for Native Americans. She also continued her work in writing and music, exposing injustices through books and magazine articles and writing the first Native American opera.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931)

Wells-Barnett — an investigative journalist, civil rights activist and advocate for women’s rights — was one of the nation’s most prominent voices against lynching. Her reporting, spurred by the lynching of three of her friends, exposed the resentments and falsehoods that often led to the killing of Black Americans. She traveled across the country and sometimes overseas to draw continued attention to racial injustice. Wells-Barnett also pushed for women’s right to vote and was a founding member of the NAACP.

Juliette Gordon Low (October 31, 1860 – January 17, 1927)

Low founded the Girl Scouts in 1912, shortly after she learned about the Boy Scouts and saw the need to establish a similar leadership program for girls. Low was artistic and athletic as a child, and that was reflected in the program she established. She also had hearing loss for much of her adult life. The first Girl Scout troop convened in Savannah, Georgia, and Low devoted the rest of her life to developing and expanding the program throughout the nation and then abroad.

Dr. Vera Rubin (July 23, 1928 – December 25, 2016)

Rubin’s astronomical research helped establish proof of dark matter. She spent much of her career overcoming gender barriers in astronomy, from the moment she declared what she wanted to study, to advocating for more women in her field. Her honors include the U.S. National Medal of Science, the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society and the Gruber Cosmology Prize. An observatory under construction in Chile will be named in her honor.

Stacey Park Milbern (May 19, 1987 – May 19, 2020)

Milbern, a leader in the disability justice movement, focused on serving marginalized communities. Milbern had muscular dystrophy and became involved in advocacy work as a teenager, advising state commissions in her native North Carolina and eventually serving as an impact producer for the Netflix documentary “Crip Camp.” Her essays, poems and speeches helped bring attention to and inspire disability justice advocates. Milbern worked on behalf of BIPOC people with disabilities up until she died on her 33rd birthday after complications from surgery.

Althea Gibson (August 25, 1927 – September 28, 2003)

Gibson broke the race barrier in championship tennis, winning 11 Grand Slam titles in singles and doubles during the 1950s. She was the first Black player to advance at both Wimbledon and the U.S. Open. Gibson was voted The Associated Press’ Female Athlete of the Year in 1957 and again in 1958, the year she turned professional. When she saw limited options in professional tennis, she began a career in golf, becoming the first Black member of the Ladies Professional Golf Association.

Flora Peir contributed reporting.