When Kate Weber of Texas was diagnosed with a form of cancer in her cervix and uterus in 2018, the then-single 25-year-old paralegal had just days to make a major decision about what motherhood could look like for her in the future.

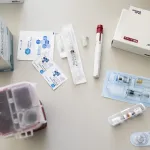

Weber needed chemotherapy and a hysterectomy to remove her uterus, her doctors explained. She was told her insurance would not cover the cost of preserving the eggs in her ovaries before lifesaving treatment would make her infertile. It was all a shock to Weber, who wanted to have biological children.

“The loss of my fertility was probably a bigger hit than the cancer itself,” Weber said.

Lynley Moses faced a similar response from her insurance company in November when she looked into preserving her eggs after a breast cancer diagnosis. She and her husband decided to dip into their 401K retirement plans to pay the initial $8,000 expense.

“It affects more than just the woman,” Moses, 33, said. “It’s her family, and everyone involved with her.”

State lawmakers are increasingly addressing the realities of fertility preservation for people like Weber and Moses who receive cancer diagnoses, then must make quick decisions about whether they want to try to preserve a chance at biological parenthood.

Not all cancer treatments cause medically induced infertility, but chemotherapy, radiation and related surgeries can damage eggs and sperm and reproductive organs. It’s not often clear at the time of diagnosis whether a cancer patient will definitely become infertile, but many don’t want to risk it.

But the costs of ensuring those patients’ chances at biological parenthood can be prohibitive — up to $15,000 in many cases, and more with additional services — and new policy proposals at the state and federal level are aimed at helping ease the burden.

In 2017, Connecticut and Rhode Island became the first states to enact policies that include insurance coverage for medically necessary fertility preservation, according to the Alliance for Fertility Preservation, which advocates for such legislation. Other states — Maryland, Delaware, Illinois, New York, New Hampshire, California, New Jersey and Colorado — have followed. The policies vary and are broadly defined, so they’re not explicitly limited to cancer patients but can include people with medical conditions like sickle cell anemia and lupus who also face treatments that can cause infertility.

Lawmakers in states including Utah and Texas introduced legislation this year aimed at requiring insurance companies to cover the costs of fertility preservation. The Utah bill, which was signed into law and went into effect this month, does not address private insurance but expands Medicaid coverage to include fertility preservation for cancer patients.

Pushback on legislation has come from some businesses and insurance firms. Several groups — including the Texas Association of Health Plans, the Texas Employers for Insurance Reform, the Texas Association of Life and Health Insurers and the Texas Association of Business — registered against a bill in Texas aimed at expanding private insurance coverage. Lobbyists representing these organizations did not immediately return a message seeking comment.

The Texas Employers for Insurance Reform described the bill in a public post as an “unfunded mandate” that would increase insurance premiums. A similar bill introduced in 2019 did not advance. The Texas legislature, which meets once every two years to pass bills, adjourns at the end of the month.

Joyce Reinecke, executive director of the Alliance for Fertility Preservation, said that after a diagnosis, people often have a matter of days to make a decision about whether they can preserve eggs, embryos or sperm.

“People are told, ‘Come back with $15,000. Literally,” Reinecke said. “They’re like, ‘What?’ Your head is spinning, because you have this life-threatening disease. It’s really overwhelming.”

In 1998 at the age of 29, Reinecke was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer that impacts the lining of the stomach. As she prepared to undergo chemotherapy, she said it was by chance that she learned about the potential effects of the treatment on her ability to have biological children.

“I was floored by that,” she said. “That has always stayed with me and driven me. Because it was apparent this wasn’t really being addressed in a comprehensive way.”

Since then, the American Society for Clinical Oncology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine have updated their guidelines on the topic in an effort to add more uniformity to the information shared with patients.

“At the end of the day, for us as a medical field that is dedicated to helping people ascertain their family-building capabilities and gain access to that medical care, it’s a no brainer that you want to make sure that they have every option available to them at the outset of a cancer diagnosis,” said Rebecca W. O’Connor, director of government affairs for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Reinecke herself underwent embryo freezing, and later surrogacy, to start her family. She and her husband had enough money to afford the out-of-pocket expenses of fertility preservation. But she knows many others, especially young people and people of color, cannot. More than 132,000 people in the United States who are 45 years and younger are diagnosed with cancer each year; approximately 80 percent will survive.

“It’s such a difficult situation to put someone in and what I have seen over the years … this haunts people,” she said. “People didn’t deal with this at the time, or they didn’t know about it or couldn’t afford it. And then they get better and then it is really a problem for people in how they feel about themselves, in dating, in knowing this and having lost this chance. I think people underestimate it.”

The Alliance for Fertility Preservation has drafted model legislation for state legislatures that would require insurance coverage for fertility preservation services when a medically necessary treatment — including surgery, chemotherapy and radiation — may directly or indirectly cause infertility. At least one bill in Congress has been introduced in recent years that would cover infertility services for people who receive government-sponsored health plans, including veterans.

After three cancer diagnoses before the age of 40, Amanda Rice of Texas was told her insurance plan wouldn’t cover fertility preservation because she had not been trying to get pregnant for six months. She was able to use savings to pay for fertility preservation, she said.

In 2017, Rice helped launch the Chick Mission to raise funds for people who need help paying for services including egg freezing and embryo freezing. (These options are often more expensive than services like sperm freezing). The group estimates it has helped more than 125 women by providing more than $850,000 in direct funds.

“I could not sit back and let this happen again,” she said. “Luckily things are starting to change. But it’s just, so much is broken in this system.”

Moses, now 33, is one of Chick Mission’s beneficiaries.

A part-time personal trainer, Moses had hoped to be starting a family around now. She’s cancer-free, but she is on medication that prevents her from becoming pregnant for at least five years. She wonders about whether pregnancy could be more realistic if she had been able to afford freezing embryos as well as eggs. But she couldn’t afford it at the time.

“It would have made things so much easier if I would have just been able to walk in like I did with my cancer appointments,” she said. “I didn’t have worries when it came to how am I going to pay for cancer treatments versus having to pay for a kid.”

Weber, who is now cancer-free but will not officially be in remission until two years after her 2019 treatment, felt like she was one of the lucky ones. Her parents quickly stepped in to financially help pay for preserving her eggs, which her insurance company deemed elective. A month later, her co-workers surprised her with an envelope of money. Weber estimates the out-of-pocket costs of her fertility preservation were in the range of thousands of dollars.

In January, Weber launched Kate’s Cause to help other women pay for fertility treatment. She has partnered with Chick Mission and a Texas cancer center to help distribute future funds through private donations. Weber also is looking ahead — her twin sister has agreed to be a surrogate for her when the time comes to carry her pregnancy.

“Being able to have the choice to start a family after a cancer diagnosis shouldn’t be an elective thing,” said Weber, now 27. “Everybody should have that opportunity.”