Growing up in Oakland, California, in the 1960s, Renel Brooks-Moon never heard Black women on the radio. She never saw women announcing sports. She never imagined herself behind the microphone.

Brooks-Moon, now 62, has been the public address announcer for the San Francisco Giants since 2000. She was the second woman to become a full-time public address announcer in Major League Baseball history and the first woman to announce a championship game for any professional sport, excelling in a role dominated by men. During her career, she’s also been a pioneer as one of the only Black women to announce in the MLB.

Her outspoken determination and history-making career is due to her time at Mills College, she says — the college she is now tirelessly trying to save.

“I literally and figuratively found my voice at Mills,” Brooks-Moon said. “I found my voice as a feminist. I found my voice as an activist. I found my self-confidence that I didn’t even know I had within me.”

At Mills, Brooks-Moon co-founded a gospel choir called the Black Women’s Collective. The courage to perform and entertain started in the choir, Brooks-Moon said, which later led her to the microphone and then to the baseball diamond. Being surrounded and supported by a close-knit group of other women helped lift up the insecure teenage girl inside of her.

“That little girl that showed up in the late ‘70s was not the same woman that left in 1981,” Brooks-Moon said.

Mills College, a private liberal arts institution serving women and nonbinary people in Oakland, announced last month it will no longer admit first-year students. Pending approval from the board of trustees, its last degrees will be issued by 2023, and it will transition to an institute that “can sustain Mills’ mission,” according to a statement posted by Mills’ President Elizabeth Hillman. The structure and programming of this institute will be discussed by the Mills community in the coming months. The college cites “declining enrollment and budget deficits” only worsened by the ongoing pandemic as a reason for its transition.

The 169-year-old school fills a unique gap in higher education. It is one of just 37 women’s colleges left in the nation. More than half of its students identify as people of color and half as LGBTQ+. Largely from student demands, Mills began to represent the larger Oakland and San Francisco community that it sat in. The college is famous as a historical hub for creators looking to experiment with music, with a focus on electronic experimentation. Mills also provides a social justice curriculum built into the academic offerings, further helping attract a diverse set of students who see a school that shares their values, many said.

As students began to see themselves represented in the student and faculty body, more students of marginalized groups began to apply to Mills knowing it was a safe space for them, alumni and students said. In 2014, Mills became the first women’s college to admit transgender students.

Brooks-Moon, who graduated in 1981 after studying classical voice and English literature, echoes the sentiments of many of her fellow classmates: Closing Mills would end a legacy of achievement and perseverance of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people.

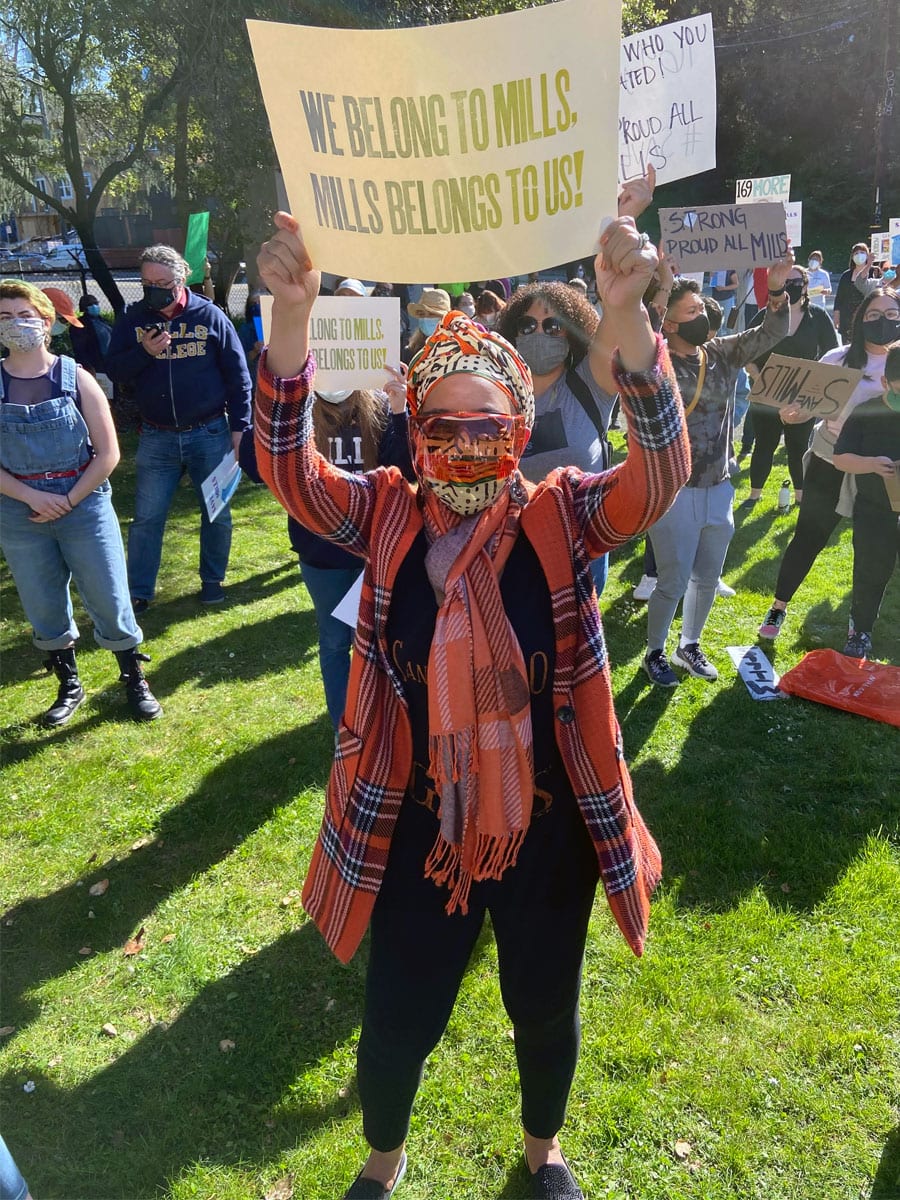

Over 100 students and alumni protested the transition on the Mills campus last month. Brooks-Moon spoke to the crowd, noting that the very place where she found her voice brought her back to speak out for its existence. This college is important now more than ever in the midst of discussions over racial injustices and hate crimes, she said, to produce a diverse set of students ready to become activists in their communities. In the coming weeks and months, she plans to meet with students and alumni to craft an action plan moving forward to reverse Mills’ decision.

The school has a history of students agitating for change. During her college years, Brooks-Moon arranged a meeting with the president to advocate for better representation of people of color and LGBTQ+ students at the school. Mills had its faults, she said, but she is proud of the progress that has been made, recognizing that the Mills she knew is vastly different today. Students are not afraid to speak up when they want change, she said. In 1990, students occupied the campus for 13 days protesting a decision to turn co-ed. They were believed to be the only single-sex college to reverse their board’s decision. Many now hope — 30 years later — that they will once again sway the board.

Though current Mills senior Dylyn Turner-Keener, who studies policy, economics and education, believes her college can improve on propelling students’ ideas forward, the “fire burning” activism of the Mills community makes it worth saving. Turner-Keener is the president of the Associated Students of Mills College, working to address key concerns specifically for students of color. She’s also found her voice as a leader to advocate for further representation on campus, respect within classroom settings and advocacy around key social issues in her community. This past year, she has leaned on her classmates to stand together against racial injustice and white supremacy.

“In times where we lost hope, [we’ve] turned into that community that gives you that hope back and especially seeing the work that past students have done … that is evidence of the hope and the fire that’s still here and it’s not burned out.”

Using her platform at Mills, she plans to keep advocating for her peers to keep this college alive so future generations of activists and leaders have a place to grow their craft.

For current junior Ashlee Davis, who studies education and sociology in a sociopolitical context and is the vice president of the Associated Students, saving Mills is about giving students the chance at higher education who may have not been given one otherwise and creating a safe environment for them to thrive in. Most universities and colleges, she said, can be a scary place for people of color.

“Save the school that gave me a shot,” Davis said. “Preserving that community for future generations to be able to come on campus — especially for BIPOC students — and not have to be hyper-aware of your surroundings and go through PTSD of racially informed trauma.”

The students Davis and Turner-Keener surround themselves with want to begin nonprofits and startups. Some, they said, want to be artists and have already painted intricate murals. It would be a loss to leave so many students hanging, they both said, recognizing that if Mills’ board follows through, some current students will not have the chance to graduate.

“We got jewels all over this campus,” Davis said. “Don’t get rid of that.”

“And those jewels come in all shapes and sizes and colors,” Turner-Keener adds.

U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, an alumna, credits Mills College for her political career, giving her the chance to earn a degree as a single Black mother on public assistance who often brought her sons to class. It’s something she never could have seen herself doing at another university, she said.

“For generations, Mills has been a bastion of diversity in higher education, providing an excellent academic education to women who are too often shut out by other institutions of higher education,” Lee said in a statement.

She called on the board members to reconsider their decision along with other students and alumni who plan to speak up at a town hall this week regarding Mills’ future. There will be a town hall meeting this Friday to discuss the future of Mills and address the concerns brought up by students and alumni.

“We need this campus to fight these battles that aren’t going anywhere,” Brooks-Moon said. “We need the women that this campus will produce to help us fight these battles.”