Be the first to read our 100 days coverage. Subscribe to our newsletter today.

On the morning of her 90th day in office, Vice President Kamala Harris headed to Greensboro, North Carolina, where she touted the administration’s $2 trillion infrastructure plan before making a stop that wasn’t on the official schedule.

It was shortly after 4 p.m. when Harris walked into the former F.W. Woolworth’s that was the site of a famed 1960 sit-in and has been transformed into a civil rights museum.

La’Tonya Wiley, a seven-year employee of the museum, helped escort Harris on a brief tour. Wiley’s green mask identified her as a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., and Harris excitedly exclaimed, “Soror! Hey, girl, hey!” as the two greeted each other.

“Every time I see her going places, doing things, interacting with people and simply doing her job, when she walks into a room, I feel like I walk in with her,” Wiley said.

Standing at the lunch counter with Harris felt like a full circle moment, Wiley said.

“She is the fruit of what I’ve worked for,” Wiley explained. “It was a moment for me to know that my vote counted. To stand in that place where, not too many years ago, a person like her, a person like me, wouldn’t have been able to sit down and be served like a human being … to now, she’s vice president of the most powerful nation in the world. It was everything.”

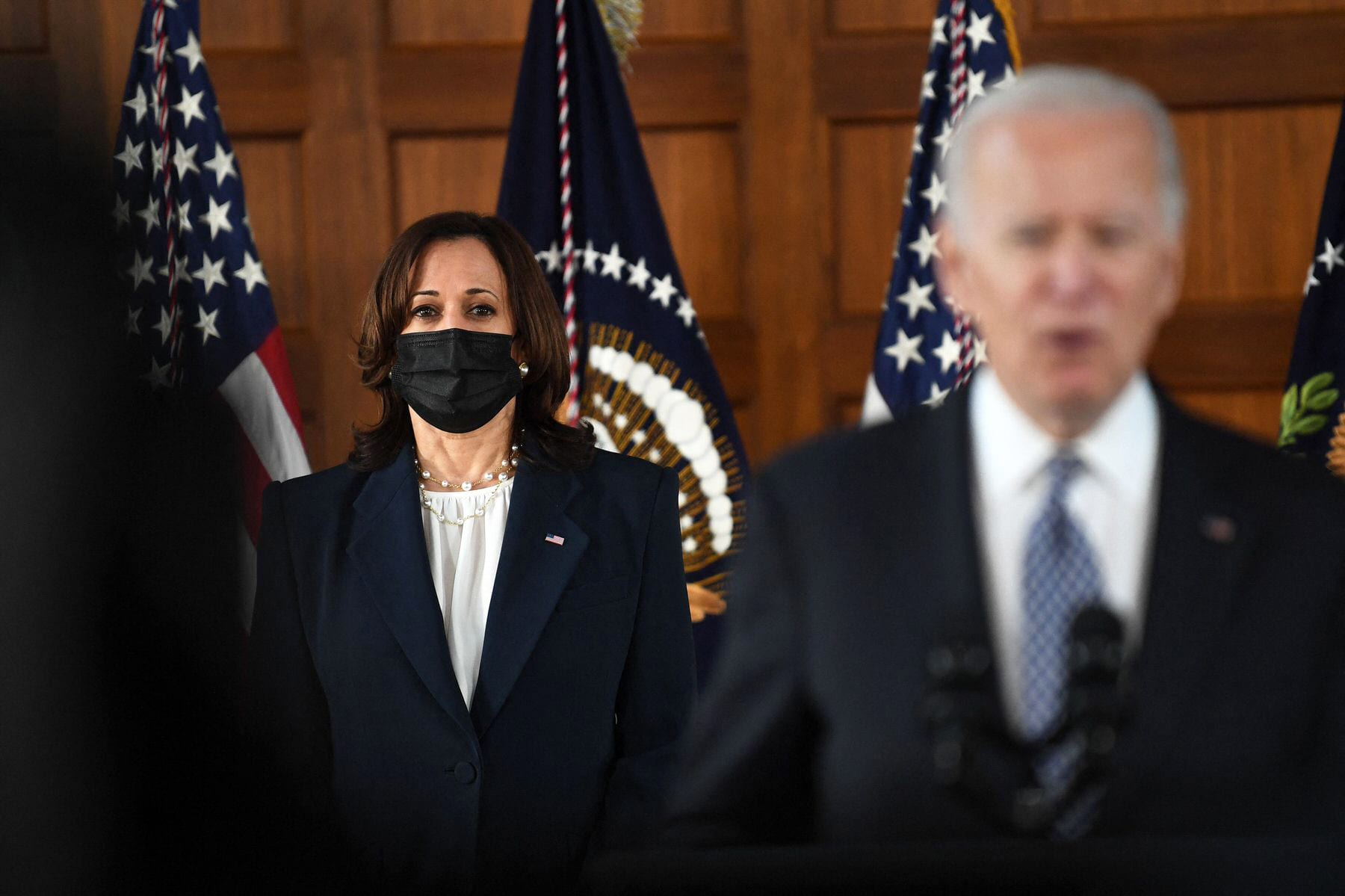

The visit to the museum after stops at a community college and bus manufacturer shed light on the roles Harris inhabits: She is both Biden’s No. 2, helping push his agenda and fulfill promises they campaigned on, and the first woman and woman of color to serve as the second most powerful person in the country.

In her first 100 days in office, observers said in interviews with The 19th, Harris has worked to solidify her partnership with her former campaign rival. And as the pair has confronted a range of issues, including the pandemic, the economy and racial inequality, she has often drawn on her lived experience and political resume to pioneer a new leadership blueprint. She is tasked with helping sell the administration’s plans and tackling problems including the root causes of the immigration crisis that have proved intractable through multiple administrations.

How America sees her in the role is important for her political future, and could impact the futures of others who don’t look like the people who have most often held power.

But being vice president also comes with automatic constraints. It is Biden’s agenda, not Harris’, that’s being implemented, no matter how much of a partnership it is. In the pandemic, many of the in-person ceremonial tasks that come with the role have also been sidelined. And, as with Biden when he was vice president, Harris’ Senate relationships have yet to translate into the bipartisanship the president has vowed. Looming over their tenure is whether they succeed or fail in the fight against a public health and economic crisis that ultimately will define both of their legacies.

Travel in the first months of the administration was curtailed due to the pandemic. But that presented an opportunity for Biden and Harris to get better acquainted as they ramped up a response to the coronavirus crisis.

Their Senate careers did not overlap, but the two met because of Harris’ friendship with Biden’s oldest son, Beau, when they were attorneys general of California and Delaware, respectively. Despite being from different generations and cultural backgrounds, they have developed a rapport that makes governing smoother, according to those who see them together regularly in the White House.

Harris’ schedule often mirrors Biden’s, and she has been a constant presence and frequent voice alongside the president: masked and standing six feet away as Biden signed executive orders in the early days; joining the president for virtual briefings on the pandemic, the vaccine rollout and the economy; meeting with foreign leaders; and co-hosting bipartisan sit-downs with congressional and state lawmakers.

Administration officials describe Harris’ leadership style as inclusive, taking notice of who isn’t in the room. Both she and Biden often translate policy through the stories of those who are most affected, recalling anecdotes of Americans — particularly women, children, those in poverty — whom they have met while campaigning or governing.

Harris’ input and counsel helped to establish her early on as a trusted adviser, said Valerie Jarrett, who worked as a senior adviser to President Barack Obama and has close relationships with people in the current White House.

“They have both demonstrated that their instincts about each other were absolutely right,” said Jarrett. “She has been an adviser on every major issue that the president has made a decision on. She has been a voice for equity and inclusion. And I just think they really enjoy each other’s company. It can be very lonely at the top, and so knowing that they both have a partner who they trust, whose opinions they each value, makes the job enjoyable at a really challenging time.”

The administration’s success depends largely on whether the coronavirus pandemic is dealt with effectively, and that means getting Americans vaccinated.

Before taking office, Biden and Harris both publicly received their first doses of the vaccine, with Harris getting her shot — the Moderna vaccine, which she often points out was developed by a Black woman scientist — in Southeast Washington from a Black woman. The optics were intentional. The pandemic has been punishing for African Americans, who account for a disproportionate number of cases and deaths. The crisis has also hit women and people of color especially hard economically.

In office, Harris continued her calls for collection of racial data around the pandemic. She often targeted her pitch to get vaccinated specifically at Black communities, in an effort to overcome a cultural hesitancy that’s rooted in medical racism.

That push has been vital, said veteran Democratic strategist Donna Brazile.

“She has played a dynamic role in making sure the administration is targeting those communities that have been disproportionately impacted, dealing with the disparities in many communities that didn’t have access to testing or vaccines,” Brazile said.

While more than half of U.S. adults have received at least one dose of a vaccine, vaccinations still lag among Black Americans, though access has largely become more of an obstacle than hesitancy. Some see a continued role for her in convincing people of color to get shots.

“They have one mission: to get everyone vaccinated,” said Alyssa Mastromonaco, former White House deputy chief of staff during the Obama administration, who suggests making Harris a key ambassador in communities to get more shots in arms.

“There’s an interesting way, in the coming weeks, to really use her to combat vaccine hesitancy,” Mastromonaco said. “Now comes the pivot where her role really starts to be defined.”

But some of the most hesitant Americans now are White Republicans, and Harris, like Biden, is viewed unfavorably by more than 80 percent of Republicans, according to the latest numbers from the Economist and YouGov. It’s unclear whether Harris or anyone in the administration is the right messenger to combat vaccine hesitancy that could threaten the country’s ability to move on from the pandemic.

As vice president, Harris has also reiterated a need for policy that helps essential and frontline workers, many of them women and minorities. She’s held roundtables with women in Congress and women activists to hear their concerns about the realities on the ground.

“The vice president has used her platform and power to sound the alarm on the struggles of women in the pandemic economy,” said Ai-jen Poo, director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, who is among the women leaders Harris met in February at a roundtable for lawmakers and activists on caregiving and the pandemic.

“Her understanding of the foundation of our 21st century economy has helped women and women of color see themselves in the economic recovery and provided hope that the recovery will include all of us, especially the hardest-hit women and families.”

In a trip earlier this month as part of the administration’s victory lap on the American Rescue Plan — the president’s $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package — Harris played saleswoman in her hometown of Oakland, California. She was greeted by U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, who had endorsed Harris for president and touts that she was born and raised in her district.

The congresswoman got her start in politics working on the pioneering 1972 presidential campaign of Shirley Chisholm that would inspire Harris’ own 2020 bid. During Obama’s presidency, Lee tried unsuccessfully to get him to land Air Force One in her political backyard. That’s why Lee said she was emotional as she saw Air Force Two landing and Harris descending the steps to the tarmac. Later, the two toured Red Door Catering, owned by a Black woman, to highlight the pandemic plan’s help for small businesses.

“I thought about Shirley Chisholm … all of the work that people have done around this country on racial justice and gender equality. I’ve been involved in so many of these struggles,” Lee recalled. “It felt like, I won’t say a load lifted, but it felt like the culmination of a long, long fight. Now, we’re still standing to fight for another day. But it was quite moving.”

Harris’s identity as a Black and Asian American woman have made her a messenger as the country grapples with violence, as well.

A planned March trip to Atlanta fell after a mass shooting that killed eight people, including six women of Asian descent, and became a forum to address the escalating anti-Asian violence in the country. Harris spoke before introducing the president at an event, condemning the attacks and pointing out that Asian Americans have been scapegoated by “people with the biggest pulpits.”

The not-so-veiled attack on former President Donald Trump came as Harris, the daughter of immigrants, emphasized the rights of everyone in America to be treated with dignity and respect.

“A harm against any one of us is a harm against all of us,” Harris said. “The president and I will not be silent. We will not stand by.”

During the trial for Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis police officer who killed George Floyd, administration officials said Biden would often ask Harris — a former prosecutor and the daughter of activists — how she thought the administration should respond to looming racial tension and the possibility of violence depending on the trial’s outcome. The two watched Chauvin’s guilty verdict together at the White House; hours later, it was Harris who spoke first, telling Americans in a televised address that the work of addressing systemic racism is long overdue and not just the problem of Black America.

She urged Congress to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which she co-sponsored as a senator.

“We are all part of George Floyd’s legacy, and our job now is to honor it and to honor him,” she said.

Activist Alicia Garza, co-creator of Black Futures Lab, said she would like to see Harris deputized to lead the process of federal interventions on criminal justice, in partnership with the Justice Department, on issues including policing, the threat of white extremism in policing and prioritizing addressing inequality in communities that lead to crime and violence.

“It’s hard to tell what’s hers and what’s Biden’s,” Garza said. “We trust Black women to lead and shape solutions that work. The upside for him is that he gets to put action with the language that Black leadership is important.”

This month during Black Maternal Health Week, Harris held a listening session that began with her acknowledging the killing of another Black man at the hands of police, 20-year-old Daunte Wright, in a Minneapolis suburb. She added the administration’s budget proposal for next fiscal year includes $30 million for implicit bias training for health care providers to address the disparity in treatment Black pregnant women receive.

“Black women deserve to be heard,” Harris said. “Their voices deserve to be respected. And like all people, they must be treated with dignity.”

The event was an example of how Harris balances her multiple identities, said Glynda Carr, president of Higher Heights, a group that backs Black women candidates.

“We wouldn’t have been talking about Black Women’s Maternal Week if it wasn’t for her leadership in the Senate that she brought to the White House,” Carr said.

Veteran Democratic strategist Karen Finney agreed.

“When the vice president says, ‘I’m doing an event on this, we’re going to talk about this,’ it raises the profile of the issue and creates more awareness on the issue,” Finney said. “Just by being there and the way she uses her platform is part of how she’s changing and molding and shaping the role in the issues she chooses to raise. And she promised she would talk about that issue.”

As the new administration has also worked to confront a growing immigration crisis that has stymied several presidents and stalled in Congress, Biden — tasked with the issue when he was vice president — has put Harris in charge of addressing the root causes of immigration from Guatemala, Honduras and Venezuela, one of his toughest political and policy challenges. Harris has been meeting virtually with leaders from those countries, including a meeting with the Guatemalan president this week to discuss America’s plans to increase aid to the region and for her to visit the country in June. She has also said she wants to visit the U.S.-Mexico border soon.

In announcing his decision in late March, Biden called Harris “the most qualified person” to tackle immigration.

“It’s not her full responsibility and job, but she’s leading the effort because I think the best thing to do is to put someone who, when he or she speaks, they don’t have to wonder about where the president is,” Biden said then. “When she speaks, she speaks for me. Doesn’t have to check with me. She knows what she’s doing.”

The assignment signals a vote of confidence in Harris’ leadership, said Jarrett.

“He’s given her the important part of immigration reform, working with the countries … to figure out how we really deal with the issue, which is a major challenge,” Jarrett said. “President Biden knows how challenging it is, and she’s representing him on the world stage.”

Finney said Harris’ role on immigration, both behind the scenes and in meetings with Biden and world leaders, also helps to further strengthen their relationship.

“Part of what you have to navigate as vice president is building that trust, and one of the best ways to do it is by being a chief adviser and realizing your political fate is tied to the political fate of the president,” Finney said. “You’re going to do everything you can to make sure the president succeeds.”

If Harris deftly handles foreign affairs, that would also strengthen her political resume, positioning her as a more well-rounded leader, said Carr, whose organization endorsed Harris for president in 2019 before she dropped out of the race.

“People are talking about who the next president will be, may that be in four years or eight years,” Carr said. “Being able to show her depth and breadth on a variety of issues will be important.”

While no one is discussing a potential run, and Biden has said he plans to run for reelection in 2024, most vice presidents have coveted the top role. Harris raised some eyebrows with a recent trip to New Hampshire, the first primary state, to stump for the American Jobs Plan.

In a CNN poll released Wednesday, 53 percent of Americans approve of the jobs Biden and Harris are doing as president and vice president. For Biden, 43 percent disapprove and 4 percent have no opinion, while those figures are 38 percent and 10 percent for Harris.

Finney said Harris is helping to normalize Black women’s leadership in executive office.

“When they say ‘the vice president,’ I see her in my head — not a White man,” she continued. “That alone is different. The thing we have to remember about how culture changes, it’s a little bit over time. Part of the way she is changing perceptions is just by being there and doing the job.”