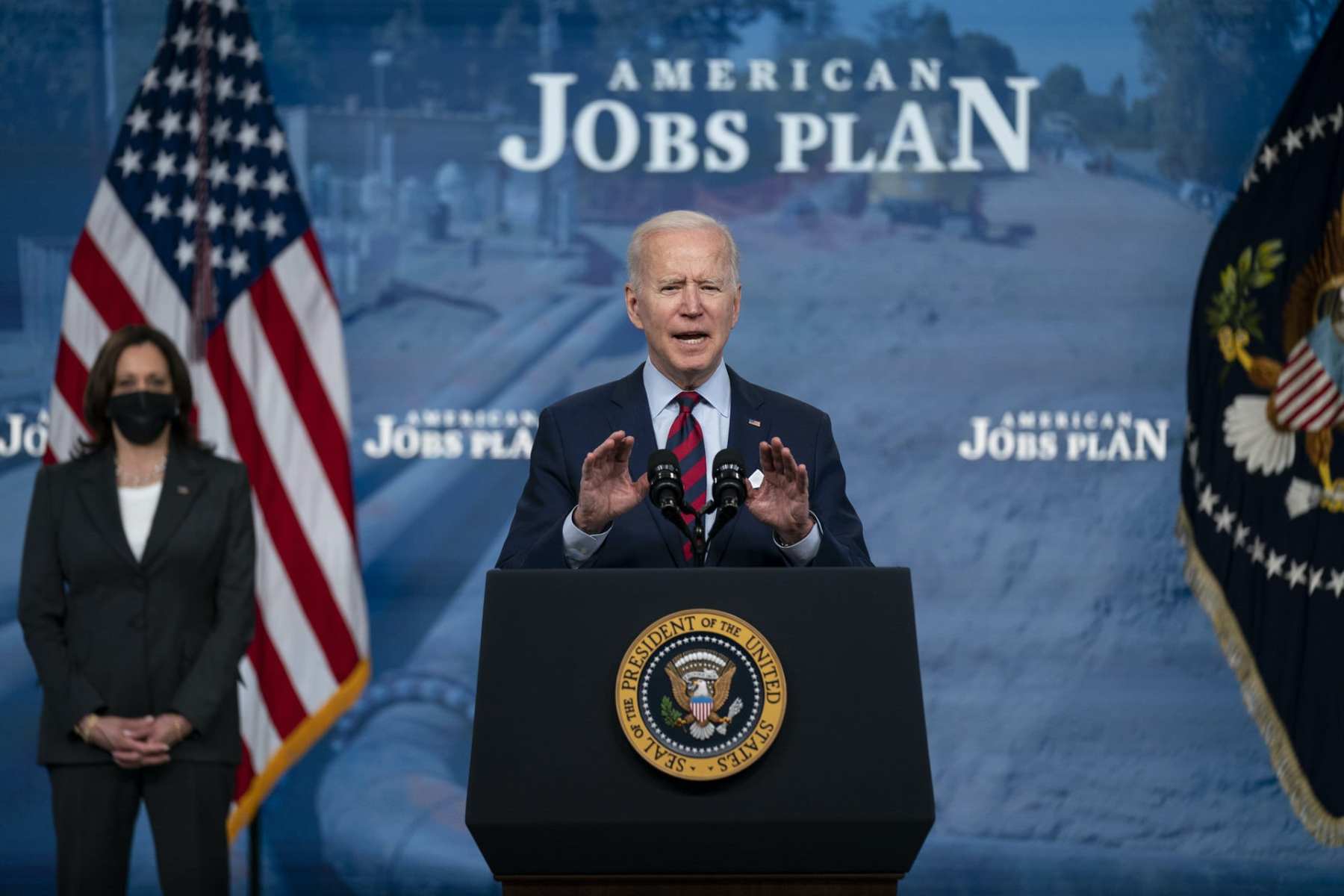

As lawmakers prepare to debate what belongs in the new $2 trillion federal jobs and infrastructure package, the Biden administration says its proposal could bridge economic gender inequities exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis.

In a memo shared first with The 19th, the administration argues the American Jobs Plan’s investments in a range of areas — caregiving, education, lead pipe elimination, violence prevention and workplace discrimination — are critical to undoing the pandemic recession’s disproportionate impact on working women of color.

“Gender is front and center,” said Shilpa Phadke, a special assistant to President Joe Biden for gender policy. “We talk about equal pay and issues of the wage gap. We know that the wage gap is steeper and more stubborn for women of color.”

The bill’s largest investments are in home care, an area that disproportionately employs women of color and that experts say have been underfunded for decades. The bill would invest $400 billion in the nation’s home care system — using Medicaid, the United States’ biggest single home care payer — as a way to both expand access to caregiving and to improve the wages and working conditions for paid caregivers.

Biden’s proposal would put $25 billion toward improving and expanding child care facilities, which already received some emergency relief in the recent American Rescue Plan Act.

Biden is expected to unveil more details about the jobs plan in the coming weeks, but his proposal is already expected to face a steep uphill battle in Congress. Provisions such as caregiver funding — while broadly popular with the American public — have drawn criticism from congressional Republicans, who argue that Biden’s infrastructure plan is too sweeping and should stick instead to roads and bridges.

In its memo, the administration lays out why it believes that caregiving solutions should be considered critical infrastructure. Both child care and home care workers typically make close to $12.50 an hour on average, per data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And in mixed-gender households that don’t have affordable caregiving available, women are more likely to leave or cut back on work to take on those responsibilities. That dynamic was on full display this past year, thanks to the pandemic’s particularly devastating impact on child care facilities.

The memo also points to the infrastructure package’s worker protections provisions — including the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, which would make it easier for workers to join a union, as well as $10 billion in funding to better enforce anti-discrimination and anti-harassment measures and create “workplaces free from racial, gender, and other forms of discrimination and harassment.”

That money would go toward agencies including the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and National Labor Relations Board, which are tasked with various worker protection duties, including making sure workplaces are safe for employees and ensuring that workers are free to organize and bargain through unions.

“There’s a lot of laws on the books now, so it’s enforcing those laws and making sure [agencies] have the resources to do that,” Phadke said.

Women in a union earn significantly more than those who are not. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests that women represented by a union earned $1,057 per week in 2020, compared to $862 per week for those who were not.

That said, even joining a union, or having access to one, did not close gender-based pay gaps. In 2020, men who were not in a union earned $1,051 — about the same as women who had union representation. Men represented by a union earned the most: $1,210.

The memo also points to expanding access to affordable housing — which Biden’s plan would direct $213 billion toward addressing — as a gender equity issue. Most households in public housing are headed by a woman, most homeless families are headed by a single woman and Black women are at greatest risk of eviction.

The bill would also put about $5 billion over eight years toward violence intervention programs, which would include job-training and preventive services for people at risk of committing gun violence, as well as people who have experienced it. Research suggests that 53 women are shot and killed by an intimate partner each month, and experts worry that the numbers have only gotten worse in the past year.

The proposal does not, however, include any proposed new gun regulations, even though women threatened with a gun are far more likely to be killed than women threatened with another weapon. The administration did not answer questions about whether recent shootings — one last week in Indianapolis, and two this weekend in Austin and Wisconsin — might spur new inclusions of any gun regulation proposals.