Whether distributed by boat, dog sled, snow machine or plane, vaccines have been given to more than half of all eligible Alaskans, according to Dr. Anne Zink, the state’s chief medical officer. The state has the highest per capita vaccination rate in the country.

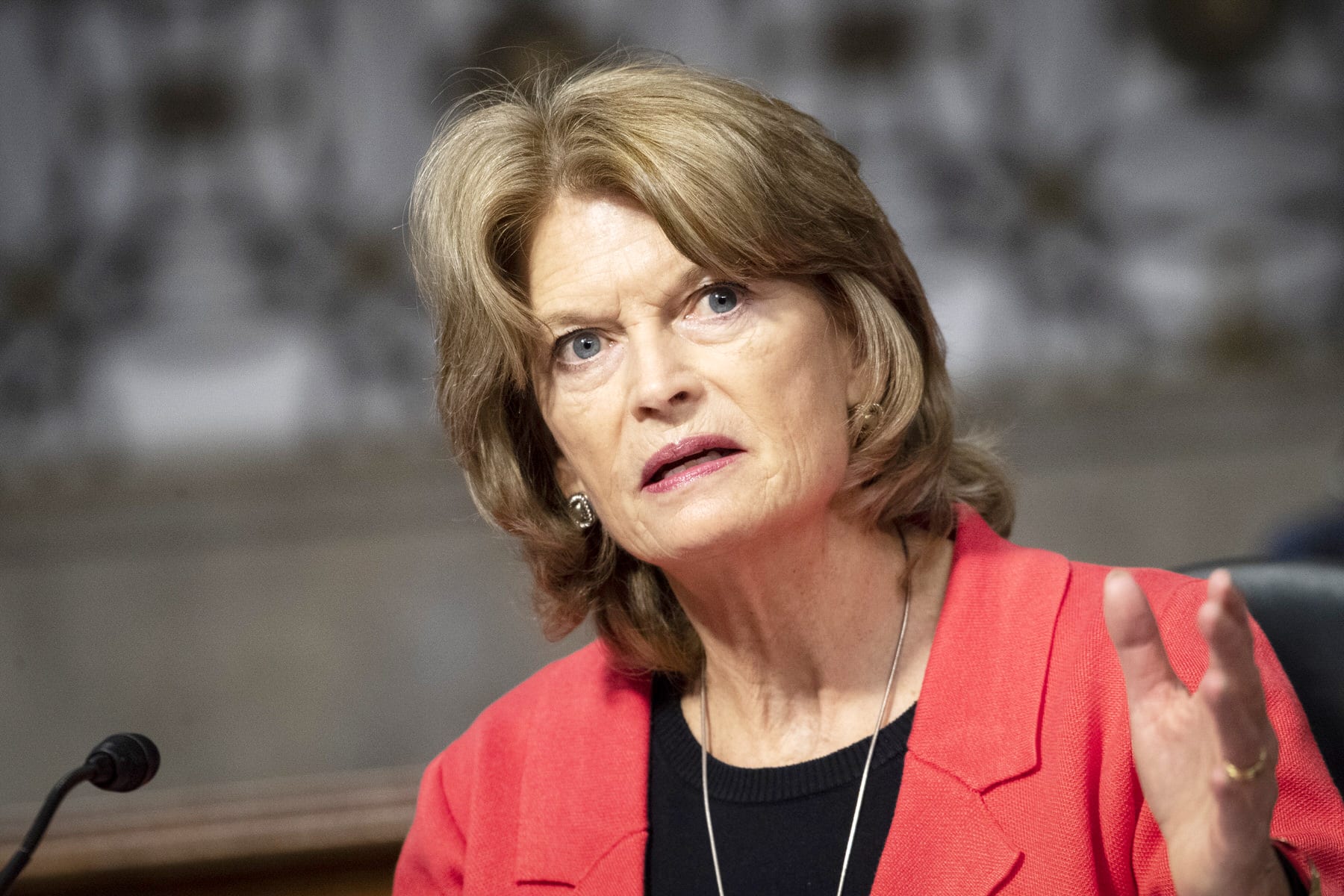

In a conversation with The 19th, Zink and Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska joined Washington correspondent Amanda Becker to discuss how the largest geographical state — bigger than California, Texas and Montana combined — has managed to blaze the trail in vaccine distribution.

Zink attributed the state’s success to three major factors: a centralized public health infrastructure, investment in public health and community partnerships, and creativity needed to overcome geographic barriers.

“We work very closely with the tribes,” Zink said. “Public health is tribal health in the state. They are incredibly intertwined. You know, over 50 percent of our testing sites are at tribal health sites, and so we built our entire vaccine team in partnership with our tribal team at every single level — from communication to planning to operation.”

The state’s pandemic response is also largely driven by the oral history of the 1918 pandemic that has been passed down by Native people, Zink said. Many tribes were devastated by the spread of influenza more than a century ago and again with COVID-19. The Alaskan Native population — which currently constitutes about one-fifth of the people in the state — has seen a disproportionate number of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths, Zink said.

“Languages were lost,” she said. “Culture was lost, and that has affected our Alaskan Native people for 100 years since then. That’s a story that looms large … and I think in a larger, cultural context, in the U.S. we have forgotten about the 1918 pandemic.”

Alaska has always been challenged by its geography and extreme weather elements, Murkowski said. “You have small, small village communities that are not accessible by road,” Murkowski said. “You have to fly in by small airplane or during the winter time, you might be able to take a snow machine or dog sled. In the summer, you might be able to go up by riverboat.”

Many of these villages are overcrowded and lack running water and sanitation, which makes it “pretty tough” to wash one’s hands, keep clean and keep physical distance from others, Murkowski said. In response to pandemics, many of these communities attempt to completely close themselves off from outsiders.

Because of this hunkering down, especially during this past long and cold Alaskan winter, Murkowski said officials are seeing “disturbing” and increasing instances of domestic violence, child sexual assault, substance abuse and suicides. Some are feeling trapped in their homes without the escape of school, work or neighboring shelters. Murkowski, along with Sen. Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire, is working to ensure that some COVID-19 relief is directed toward these victims.

Though there didn’t seem to be a big uptick in reported suicides or homicides last year, Zink said the data showed a significant increase in the state’s call lines overall.

“I am concerned that we will see this linger,” Murkowski said. “It may be that we will actually see it grow in the aftermath of COVID … I am worried about what we will see going forward, and the trauma that many will carry with them long after COVID is gone.”