Miles Griffis is invisible in the pandemic.

On paper, he is not high-risk for the virus and never had COVID-19. Until last year, he was exercising four or five days a week, traveling the globe as a travel writer and sleeping under the stars.

“I was very active,” he said. “I’d spend most of my weekends hiking or backpacking or skiing. I really enjoyed being outdoors.”

In February 2020, his left leg started to ache. He was hit with bouts of nausea followed by headaches. His doctor tested him for blood clots, and all bloodwork came back normal. He was told he was fine.

Griffis now knows he is suffering from long COVID, the after-effects of the virus that plague up to a third of those infected. More than a year later, Griffis is still suffering extreme fatigue, neurological issues, headaches, heart palpitations and tingling in his left arm and leg. He can only work at about half capacity. Still, because he had COVID in February, he didn’t have the benefit of getting tested. By the time he got tested for antibodies, the test came back negative, something a lot of his peers who have long COVID also experienced. It took him months to find a doctor to diagnose him.

Griffis seems like those least at risk in a pandemic, and by all federal demographic standards he might be. He’s 28 years old, White and fit. Except, Griffis identifies as queer.

“Even just in my experience as a cis[gender] White gay male, I’ve been gaslit by three different doctors until I found one who actually believed me,” he said, noting that doctors often dismiss the experiences of their queer patients.

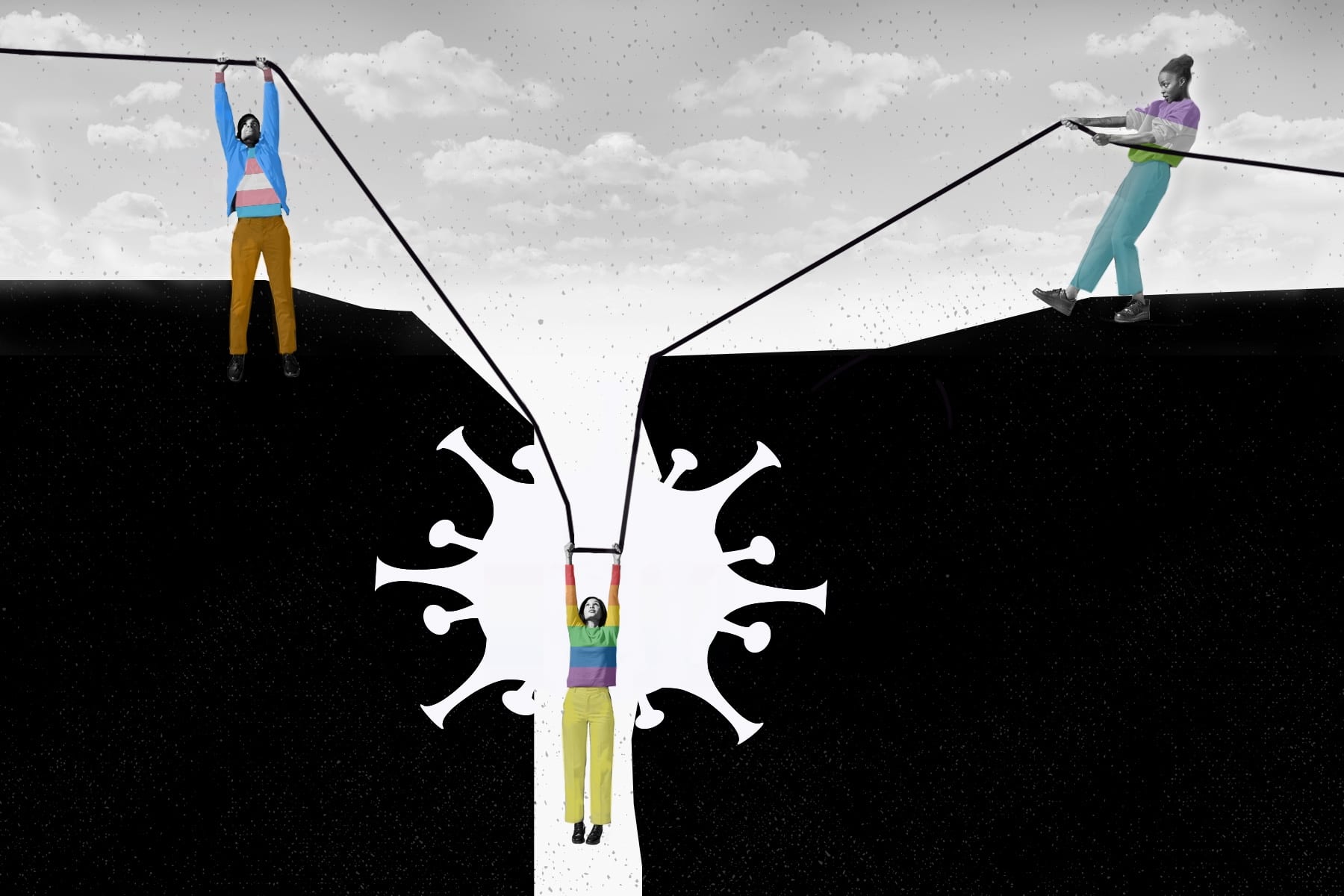

For the past year, LGBTQ+ people in the United States have navigated a virus that most experts say has disproportionately but silently ravaged their communities. Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that LGBTQ+ people face myriad health disparities that put them at higher risk for complications from the virus.

Still, despite those increased risk factors, the federal government hasn’t collected data on how many queer people have been infected with or died from COVID-19.

Dallas Ducar, the CEO of Transhealth Northampton, a transgender health clinic opening in western Massachusetts this spring, said this invisibility is a problem, especially when you consider how the pandemic has affected people of color.

“There’s a lot of talk around health equity, but because we don’t have the data behind this, we’re not going to be able to actually make a case,” Ducar said. “If we don’t track the impact of COVID on the queer community … we will not necessarily have the ability to make an argument that the resources and support are necessary.”

According to the CDC, an estimated 65 percent of LGBTQ+ Americans have preexisting health conditions such as cancer, asthma, heart disease, kidney disease, HIV and diabetes that put them at higher-risk of severe illness and death in the pandemic. Those challenges are often the product of discrimination, and lack of access to food and medical care, according to the CDC.

Dr. Robbie Goldstein, director of transgender medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, worries that many LGBTQ+ people have not been tested for COVID-19 because of those barriers.

“They’re less likely to have a connection to a primary care practice or a health system that can provide them with the tests they may need,” he said.

Studies show that LGBTQ+ people face high levels of discrimination in health care. A 2017 College of American Pathologists Survey found that 8 percent of people reported being refused care because of their sexual orientation, and 29 percent said that they had been denied health care because of their gender identity.

“I think we will probably see that they’re going to be less likely to be vaccinated when eligible for vaccination because they don’t have that connection,” Goldstein said.

The Human Rights Campaign and The Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law have launched large-scale efforts to study the impacts of COVID-19 on queer people in the United States. Out Boulder County, a Colorado-based LGBTQ+ organization, published its own study on how the virus has impacted the community.

That organization reported that LGBTQ+ people would be almost twice as likely to hesitate about getting vaccinated as their straight, cisgender peers; 17 percent of queer respondents were reluctant to get vaccinated compared with just 9 percent of the general population.

Still, some data will inevitably be lost, advocates say, particularly when it comes to older queer people who have been cut off from their support networks. Many faced isolation before lockdowns because their families of origin had been unsupportive and their friends have passed away.

Elizabeth Coffey-Williams, 73, saw firsthand as those in her queer senior housing center in Philadelphia were shut off from the world.

“Most of our peers, most of the extraordinarily beautiful people who live in my building, have another level of isolation, because an extraordinarily large percentage of their peers, their friends, their chosen family, they died at a young age,” Coffey-Williams said. “So when you put all of that together, the numbers of available connections are very low.”

David Vincent, chief program officer for LGBTQ+ elder organization SAGE, said that 30 percent of his organization’s clients lost access to services when the pandemic hit, in part because many seniors don’t have internet.

“When we left the agency on March 13, [2020], we distributed the list of all of our active clients, and when I say all of them, I mean over 4,000 active clients,” Vincent said.

A staff of 90 people made calls to those clients and asked if they were connected to services and if they had food.

“And we did this every single day,” Vincent added.

On one call, a homebound senior reported that he was fine, Vincent told The 19th. He was more worried about the younger staff of SAGE, who had never lived through a crisis. “He’s like, ‘My question to you is, how do you feel? Because I’m used to being homebound. And I’m used to being isolated. And I know what this feeling is, but you don’t. So how are you doing?’” Vincent recalled.

In this moment, many see history on repeat. The AIDS epidemic devastated a generation of LGBTQ+ people. Among those bearing the brunt of anger against initial government inaction was Dr. Anthony Fauci, who earned the trust of AIDS advocates over time. Fauci, the nation’s top disease expert, declined to be interviewed for this piece.

“All of a sudden, we became the client under phone call with someone who’s had experience doing this,” Vincent said.

The truth was Vincent and his colleagues were struggling. Any help was going to come from within the community.

Nada Merghani, 24, has been a part of those community efforts in Charlotte, North Carolina. Merghani has helped facilitate the delivery of thousands of meals with their organization Feed the Movement CLT.

Merghani is among countless queer organizers across the country that organized mutual aid programs over the last year, fundraising for medical care, housing and food from within the communities in need and distributing those resources back out, no questions asked or applications required.

“For a lot of folks, it was already bad prior to the pandemic,” Merghani said. “And now they’re in this situation where things are significantly worse, the structures and systems of support they had previously, they don’t have anymore. A lot of mutual aid efforts are completely exhausted constantly of funds, of energy, of capacity and are doing their best to fill the gap.”

In Memphis, Tennessee, grassroots organizers have battled homelessness among transgender people through a tiny homes project called My Sistah’s House. A GoFundMe in support of homeless Black trans women, raised nearly $3 million during the pandemic.

“The same people who asked us for support are also the same people who donate to keep us sustained, because sometimes you have a good pay week and sometimes you have a bad pay week,,” Merghani said, noting that this is especially true for people in the service industry, which 40 percent of LGBTQ+ people work in.

Imara Jones, a journalist who hosts the TransLash Podcast, used her platform to fundraise for mutual aid early on in the pandemic.

“Black trans communities just have a very, very long history of grassroots funding organizing to help the people who are most in need in our community,” Jones said. “What happened during COVID is that that was able to be translated in a way that was relevant for the digital age, and then to be able to raise large sums of money to be able to move to people who are in need.”

But Jones adds that trans people continued to struggle with meeting basic necessities like food and housing over the last year. Similarly, Merghani said mutual aid efforts, while heartening, shouldn’t need to exist.

“It’s awesome that we’ve been able to give out food, give out money, do whatever we can,” Merghani said. “But also, we’re a group of a bunch of 20-something-year-old queer and trans folks who are doing our best while also working or just trying to survive … We’re not an entity made to handle massive scale impoverishment of hundreds of thousands of people in this city.”

Some LGBTQ+ advocates say the Biden administration represents hope of addressing inequities of facing queer people in the pandemic. President Joe Biden has already made good on several campaign promises to advance LGBTQ+ rights.

Among the most important, said Jones, are his appointment of Dr. Rachel Levine, a transgender woman, as the assistant secretary at the Department of Health and Human Services.

“I think that so many of the things that we’ve been thinking about today are things that she could work on and help shift,” Jones said.