Rupali Limaye quickly noticed the pattern. The Washington, D.C.-based expert in vaccine hesitancy had been working with churches with predominantly Black congregations to address questions people have about the new coronavirus vaccine. There were themes: Was the vaccine really safe? What about the side effects? And had it been developed with people like the questioners in mind?

And the people asking were almost all women.

“We’re very much seeing a divide,” said Limaye, an associate scientist at Johns Hopkins University. “I think especially Hispanic women and Black women, they do not have confidence in this.”

As President Joe Biden works to ramp up the coronavirus vaccination effort, pushing more doses to states and launching efforts to purchase more vaccines, that lack of trust could pose a critical challenge.

Recent surveys suggest that skepticism about coronavirus vaccines is declining — a promising trend in the nation’s quest for herd immunity. But a recent poll suggests that most Americans aren’t confident enough to take a vaccine as soon as it’s available to them, stoking fears among health experts that simply shoring up the number of available vaccines won’t be enough to boost immunization rates.

Although the data is mixed, polling suggests that women may be particularly concerned about the vaccine’s safety, which experts said stems from a variety of concerns that will take deliberate, multi-pronged outreach to assuage. Any gender gap would hold powerful implications, given the role women typically play in helping their family members navigate the health system. Experts say women will play a critical role in helping address broader concerns about vaccine skepticism, which have received little attention from the federal government.

“We have to break down all kinds of barriers,” said Folakemi Odedina, a professor at the University of Florida College of Pharmacology, who has been conducting focus groups about people’s vaccine attitudes. “We have to break down disinformation barriers and misinformation barriers and make sure we answer the questions people have.”

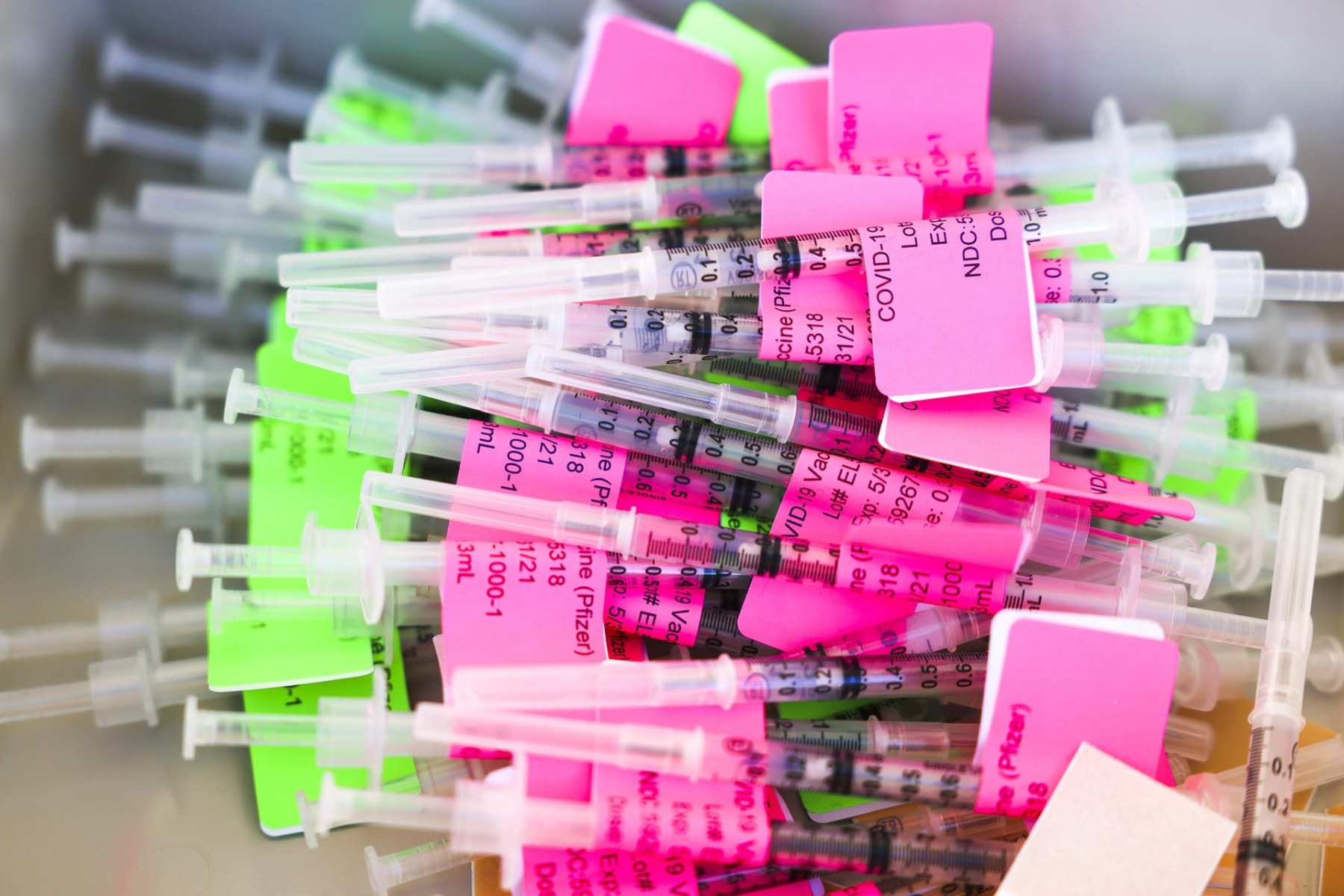

The science is clear: Both of the currently available COVID-19 vaccines are safe and incredibly effective. There are some relatively common side effects, including pain, chills and fatigue, as well as highly rare cases of anaphylaxis. (In the first nine days of vaccination, 21 out of 1.9 million doses resulted in anaphylaxis.) Experts overwhelmingly agree that the massive benefits of taking the vaccine far outweigh the risks.

Still, polls conducted in December by Pew, National Geographic and Gallup all suggest that women were more likely than men to say they did not feel comfortable taking new coronavirus vaccines — with many worrying the process had been rushed or that side effects had been downplayed. None of those polls accounted for people who identified as neither men nor women. Those polls, however, were taken before the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines had actually begun being dispersed.

It’s unclear if the gap still exists now that about 25 million Americans have actually received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine. All evidence suggests that the more people someone knows who have gotten a vaccine, the less likely they are to be concerned about taking one themselves. A poll late last month from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) found no meaningful gender gap on the question of vaccine hesitancy, though it did find that, overall, only 47 percent of people said they have been vaccinated or will take one as soon as possible. Almost a third of respondents said they want to wait and see.

That poll showed women were significantly more likely to voice concerns about the vaccine, even if that didn’t translate to greater hesitancy. A majority said they were worried that they may experience serious side effects from COVID vaccines, or that the vaccines were not as safe or effective as had been promised.

“It points to how complicated people’s views about making the choice are,” said Liz Hamel, a KFF pollster. “People feel like a lot of it is unknown at this point, and there is a lot of concern about side effects.”

Experts are quick to note that vaccine skepticism is not the same as coronavirus denialism — many women expressing concern about the vaccine also told pollsters they fear contracting COVID-19 and understand the virus’ consequences. Rather, the data speaks to broader concerns people have about whether, for instance, scientists faced political pressure to quickly develop a vaccine.

Meanwhile, some forms of misinformation, including false claims that the vaccine could cause infertility in people with uteruses, are more likely to concern women, experts said. For instance, those who are pregnant could be more worried about the fact that no available vaccine was specifically tested in pregnant people. (Medical experts on pregnancy say the theoretical risks are low for pregnant people or their fetuses.)

And for Black women and Latinas, there are particular concerns about historical discrimination by the health care system — and fears that people will be offered new vaccines early on not because they are safe, but because of a medical legacy of using people of color as subjects for experimentation. An October poll found rates of skepticism higher among Latinas than Latinos, but there’s no polling that specifically compares Black women against Black men. Experts say, though, that the trends of vaccine concern suggest gender gaps likely do exist among those specific groups.

“There are groups of people who are distrustful not specifically of vaccines per se, but of government programs and public health programs and medical programs in particular, and that’s got its roots in a history of violation of human rights and disrespect of people of color by health systems and biomedical science,” said Ruth Faden, a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University. “They have a justified or healthy distrust based on experience.”

Furthermore, experts note, women are more vulnerable to vaccine concerns simply because they are more likely to be the ones researching and reading about them, including news stories that spotlight negative side effects or internet posts amplifying misinformation. In mixed-gender households, women are relied upon to navigate major health care decisions for not only themselves, but their parents, their partners and their children.

“Women are usually the ones making health care decisions for the family. They are the ones seeking information, reading about clinical trials,” Limaye said.

And because women so often are the ones making health care decisions for their families — for instance, helping their parents navigate complex online vaccine sign-up systems — any skepticism could have ripple effects.

“If women who have older parents or other [older] relatives are … not eager or are concerned about vaccines, obviously it will be much more difficult for older relatives who rely on younger women to get health care,” Faden said.

For policymakers and public health officials, then, the challenge is addressing potential vaccine skepticism among women, while noting that reasons for that skepticism vary. That means tailoring messages to specific groups based on their individual concerns, relying not necessarily on national figures, but local ones who are familiar and more likely to be trusted.

“People need to see themselves in the people championing the vaccine. They need to see women of color, they need to see people whom they can relate to,” Odedina said.

Take Jessica Ross, a 24-year-old public health student in Atlanta. Ross understands the threat coronavirus poses — her godfather, who is diabetic, contracted COVID-19 earlier in the pandemic. Both of her parents have gotten vaccinated. She wears her mask in public and tries to avoid people who don’t do the same.

But for Ross, a 24-year-old Black woman in good health, getting the vaccine isn’t a no-brainer — at least not until more people she knows personally have taken it and can vouch for it.

“History shows us that Black people have been tested on and suffered the consequences, whereas other groups may not have had the same experience,” she said.

Seeing Vice President Kamala Harris get the vaccine helped somewhat, she said. But more important is the testimony of people whom she knows and who have lived experiences similar to hers. So far, she said, it’s even helpful just knowing that her parents have gotten the vaccine and not had any negative side effects.

“As time goes along, I will eventually get the vaccine, but there is some hesitancy,” she said. “I’m just trying to watch and see how other people respond to it that are currently taking it.”