When Congress finally passed a $900 billion stimulus package in December, extending eviction moratoriums, unemployment insurance and stimulus checks, it notably left one provision out: paid leave.

It was a policy that last year brought the United States as close as it had ever come to offering a universal policy — already available in many countries in Europe and around the world — that allowed workers to take time off if they felt sick. During a pandemic, such a policy was paramount.

Studies found that paid leave effectively curbed the spread of the virus. Without it, many low-wage workers who rely on their jobs to keep their families fed may have gone to work anyway. Still, only about 20 percent of workers were covered because of an exemption that allowed companies with fewer than 50 employees or more than 500 to skirt the rule.

And yet, when it came to extending the policy into the new year, as cases of coronavirus were again surging, the federal paid sick leave mandate was left to expire. The only allocation that remained was for employers, who could choose to let employees use whatever remaining hours they had from the 2020 provision — which offered 80 hours of paid sick time at full pay or at two-thirds pay to care for family members — through the end of March.

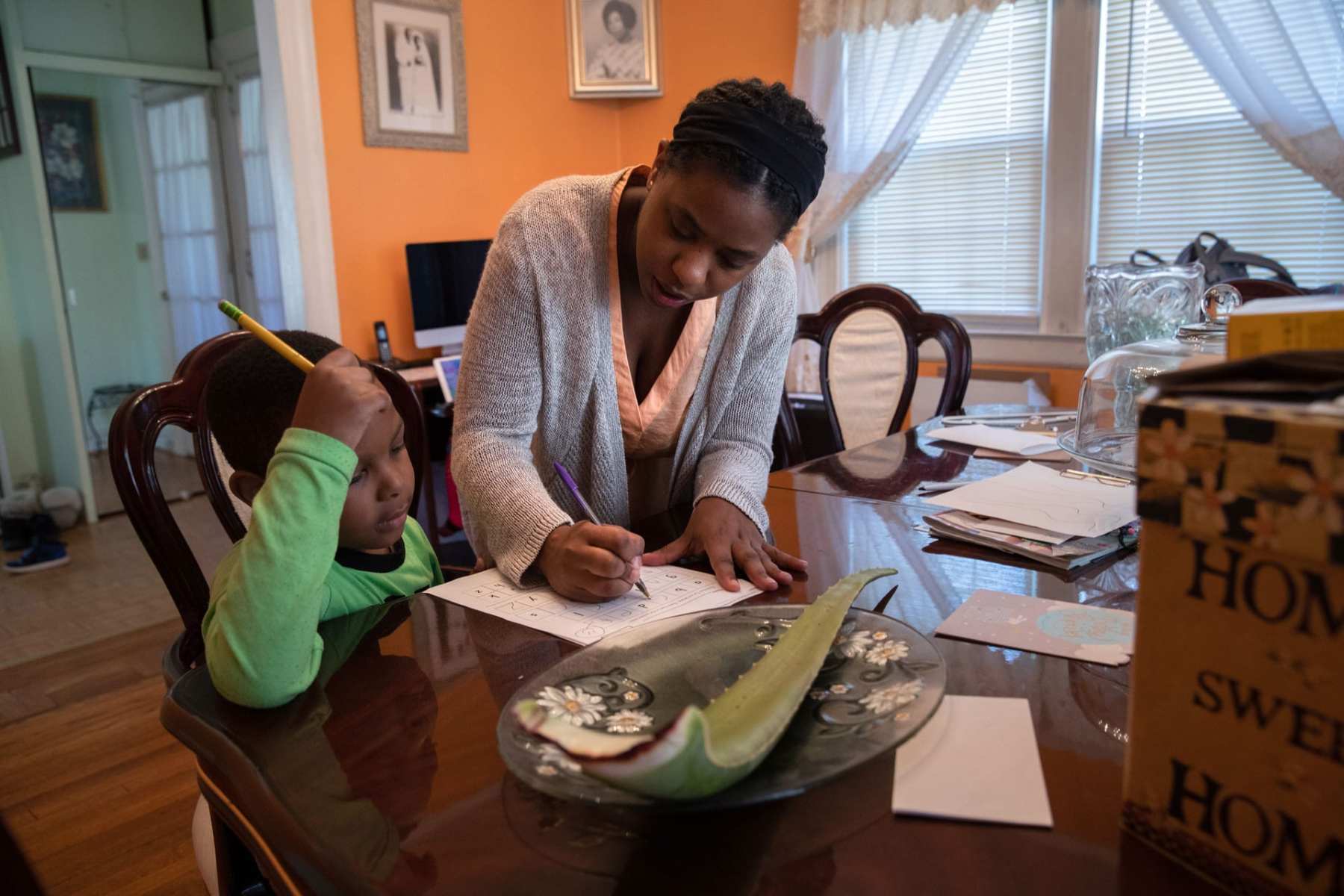

The policy helped women most of all because of who could access it. Low-wage workers are by far the most likely to not have paid sick leave, and women make up nearly two-thirds of the 40 lowest paid jobs in the country. Mothers who needed help with child care could use paid sick leave to care for children whose daycares or schools had closed for part of the year. When the provision wasn’t extended, it left advocates like Dawn Huckelbridge, director for Paid Leave for All, at a loss.

“There is a perception that this is something we can’t afford. The opposite is true, though,” she said. “It’s one of the most cost-effective tools to handle the pandemic and help us build back in our economic recovery.”

With a new administration in place now, that may be about to change.

President Joe Biden has committed to extending paid sick leave and its counterparts, paid family and medical leave. In an economic plan released last week, the president outlined his desire to reinstate the CARES Act paid leave policy and extend it through the end of September, eliminate the carve-out that exempted businesses of certain sizes, and expand the paid sick, family and medical leave benefit to 14 weeks.

Biden has also named several proponents of paid leave to his top economic Cabinet positions.

Janet Yellen, the nominee for Treasury secretary, emphasized the need for the policy several times during her first confirmation hearing on Tuesday.

“I feel this is a really critical area, both because of the pandemic and longer-term,” Yellen said. “The availability of child care and paid leave greatly affects the ability of women to participate in the labor force.”

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, who Biden has nominated for Labor secretary, helped pass a paid family leave policy in Boston and championed a larger push in Massachusetts. Similarly, Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo, Biden’s nominee for Commerce secretary, signed a paid sick leave bill into law in 2017, which by 2020 let workers accrue up to 40 hours.

Sen. Patty Murray, a Washington Democrat who has been a vocal advocate for paid leave, said an unpaid sick leave policy was the very first she helped get passed in the Senate in 1992. Since 2004, she has introduced a paid sick leave policy every congressional session.

Murray said 2020 made abundantly clear why a policy like that should have been in place already, and it helped legislators who otherwise have opposed it before embrace the idea, as evidenced by the bipartisan passage of the paid sick leave policy in the CARES Act. About 82 percent of voters, across party lines, support a permanent paid sick leave policy, according to recent polling by the National Partnership for Women and Families.

With a Biden administration now in power, it’s more likely the topic will be revisited, said Murray, who is the top Democrat in the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee.

“Now, to be actually at a point where people really understand the need for paid leave versus unpaid leave … we are closer,” Murray said. “The administration fought us and wouldn’t let us [get it] in the last package. But I think everybody, if they just look around at their own family, their own community, their own constituents and hear the stress in people’s voices as they try to manage themselves in this pandemic and at work in general, I think we can get the support we need, and that’s what I’m counting on.”

To implement a national paid sick leave policy, whoever is leading the Department of Labor (DOL) is critical.

The Cabinet role is influential in shaping the administration’s worker-focused priorities — and it will be more so in a Biden administration. Biden has positioned himself as a strong, pro-labor president, and he has close personal ties to his chosen nominee, Walsh, who will no doubt be an important counselor.

During the pandemic, the DOL’s power over paid sick leave policy was evident. Under former Labor Secretary Eugene Scalia, the department tried to roll back some of the paid sick leave provisions in the CARES Act. In August, DOL issued updated guidelines for employers that blocked workers from taking paid sick leave for child care purposes if their children had any opportunity to return to school in person. If parents chose to keep their children in remote learning, they could no longer access the benefit.

“There were clearly continued efforts to chip away and to undermine it by the Department of Labor, which [also] really never fully implemented it, was not doing the necessary outreach and education,” Huckelbridge said.

Murray, who worked to close some of the exemptions in the law last year, said voices like Walsh’s and Raimondo’s could change the trajectory of paid sick leave laws in the United States.

Walsh would be the first former union member in almost 50 years to become Labor secretary if confirmed. He helped pass a paid parental leave policy in Boston in 2015, giving city employees six weeks to care for a newborn or adopted child. He also supported the statewide push for paid family and medical leave that went into effect this month.

Deb Fastino, the executive director of the Coalition for Social Justice and a co-chair of the Raise Up Massachusetts coalition, the groups that brought the paid leave bill to the state, said Walsh’s support helped cement its passage.

“The way I see it is when you take Walsh’s proven leadership at both the state and municipal levels, and you add President Biden’s strong track record for supporting work and families, we can’t lose,” Fastino said.

Raimondo was a vocal supporter of a bill in Rhode Island that gave workers five paid sick days, calling it a “basic right that Rhode Islanders deserve.” Because that policy was already in the books at the start of the pandemic, and thanks to quick action by Raimondo in March, one study by the Urban Institute found that workers were able to access the benefits in the CARES Act more quickly.

“The pattern in these data is clear,” wrote the Washington Center of Equitable Growth in an analysis of the study. “The number of workers requesting new leave or continued time away from work rose dramatically in the early weeks of the pandemic. These workers accessed benefits relatively early in the public health crisis.”

That’s the kind of swift action Murray hopes could come with a new administration.

“Having these voices inside the administration that have worked and passed these kinds of policies and understand the implications for our families is just really essential,” she said.

Much of the opposition to paid leave from the business community is built on the belief that it creates an insurmountable burden for businesses, especially small businesses with few employees.

The National Federation of Independent Business, a vocal opponent that represents small businesses, has particularly opposed what it called a “one-size-fits-all” mandate that would make it harder for smaller firms to operate if employees are out on extended leaves.

The airline industry has also come out against local or statewide paid leave policies that it argues complicates operations for airlines staff who work across state lines. Some of the policies go into effect when crews spend a certain number of hours within the state.

Airlines for America, the trade group that represents the major airlines, including American Airlines and JetBlue, has filed lawsuits against Massachusetts and Washington, saying their paid leave policies go against the federal regulations that apply to the industry.

Airlines for America did not answer questions from The 19th about the potential for a federal paid leave policy or whether it had been in communication with members of Congress or the new administration on the topic. Instead, the trade group issued a statement saying many of its airline workers get paid sick leave benefits through their union contracts or airline policies.

“We look forward to collaborating with the new administration to restore travel in a manner that prioritizes the safety and wellbeing of travelers and employees, as well as to speed the recovery of our industry, the nation and the world from the COVID-19 pandemic,” Airlines for America said in a written statement.

Studies on the impacts of paid sick leave on employers have found that it hasn’t measurably disrupted the labor market, said Nicolas Ziebarth, an associate professor at Cornell University and an author of several studies regarding paid sick leave.

Ziebarth’s most recent study, on how paid leave helped prevent the spread of COVID-19, found that, when controlling for all other factors, states that got access to paid leave through the CARES Act provisions saw 400 fewer confirmed coronavirus cases a day.

He said he has seen increased support this year for the policy.

“It is less complicated and less complex than health insurance and less ideologically driven. It’s not as polarizing,” Ziebarth said. “I do believe when voters demand it, you will get it in more and more states.”

The other factor to overcome will be a cultural one — the belief that if you’re sick, you should pop a pill, come to work and power through, Ziebarth said.

It’s part of the reason that workers like Beth Fauteux, a mother of two in New Bedford, Massachusetts, hasn’t pushed her employer to enact its own policy. Fauteux, a line cook at a small restaurant, didn’t have access to paid sick leave last year because her employer is exempt.

But she has also seen how difficult it is to go to work when you’re the only person available to care for your children. Both her kids are in hybrid school models that require in-person learning half the week on opposite days.

“Working in a restaurant, if you are busy, you can’t just answer the phone or answer an email. It’s hard to leave. And if you leave in the middle of a rush, it’s really screwing over your coworkers,” said Fauteux, 37.

It’s a constant tension when she has to leave to pick up one of her children or tend to her mother, who is sick. Fauteux was also one of the few employees who didn’t lose her job when the restaurant cut hours and downsized due to the pandemic, so “you feel like you’re lucky to have kept your job, but you want to make sure you can prove you can do the job,” she said.

She also knows the benefit of a paid leave policy, having worked with groups in Massachusetts to pass the state law. But as a low-wage worker who relies on her job, she’s afraid to bring it up to her employer.

“I’ve worked very hard to make sure people have access to it and that it got passed, but I still have an internalized guilt about using it myself,” she said.

Those burdens are heaviest on women, who more often have to measure whether they can take leave — and whether they should.

I do believe when voters demand [paid leave], you will get it in more and more states

Nicolas Ziebarth, associate professor at Cornell University

At Eric Sorkin’s maple syrup manufacturing and retail business in Vermont, Runamok Maple, it was his women employees who were most using the CARES Act-provided sick leave policy, particularly the child care piece.

Having federal support to offer leave through a tax credit helped his business avoid outbreaks this year, Sorkin said, and stay in operation. He employs about 70 people and many of them perform work that can’t be done remotely, so offering paid leave was critical.

But when it expired, he had to make a decision.

“We just decided that we just don’t have a realistic choice but to continue paying for it, regardless of where [the funds] came from,” said Sorkin, who is the co-founder of the business with his wife, Laura Sorkin. “Frankly, once we made that decision I stopped thinking about it. Well, it’s going to cost what it’s going to cost.”

For him, the trade-off has always been clear. It’s a matter of staying in operation and staying healthy.

“It’s such a small cost and such a clear benefit,” he said. “I’m just always appalled with what an easy choice it is and how it’s continually not made.”