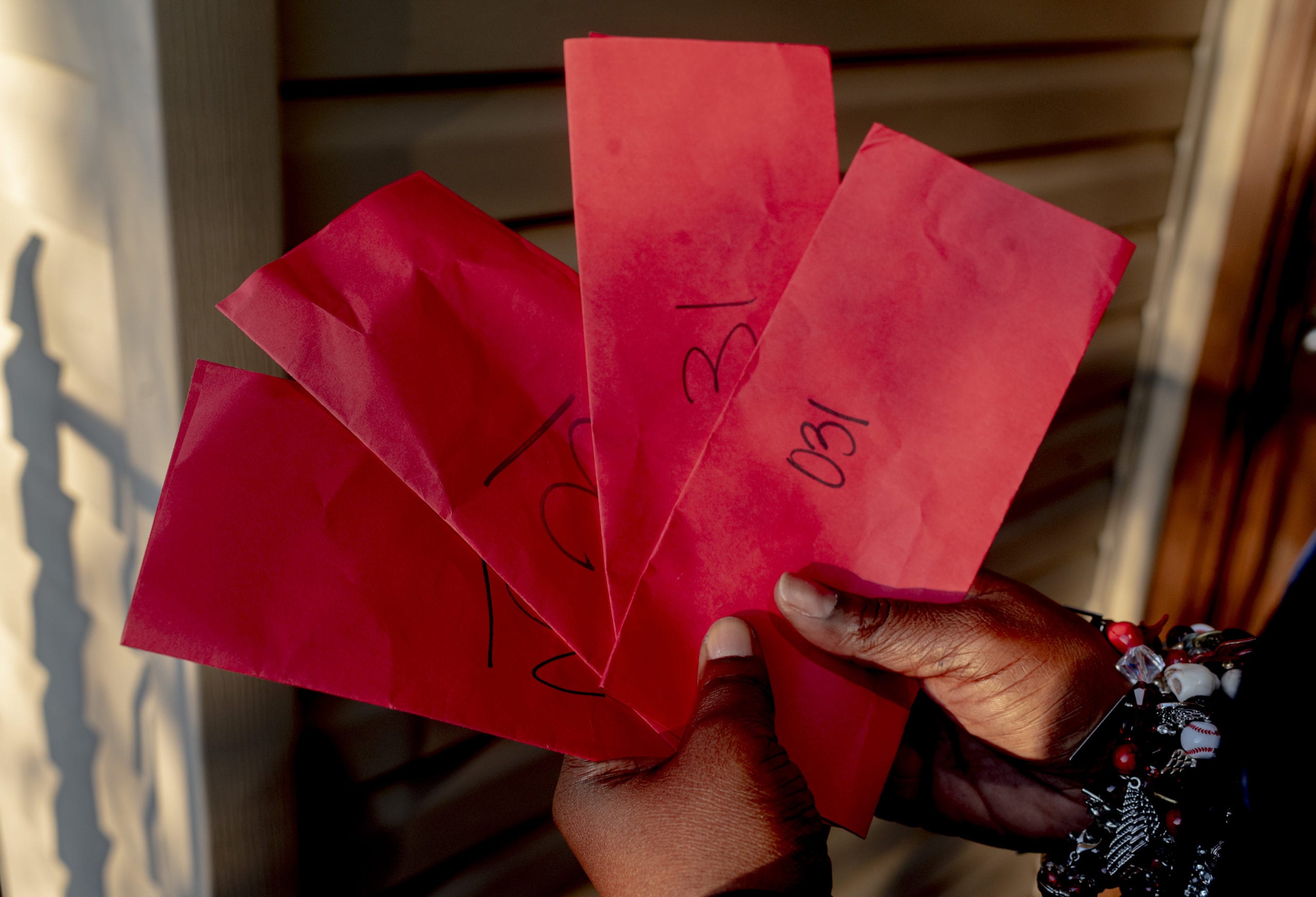

The red slips showed up at her door shortly after the last of the federal unemployment payments ended, after her job was cut, after she buried her only son.

Her landlord threatened eviction as the pandemic raged outside and grief raged within. Why was God testing her in this way? Why was he letting the pain fill her chest, weigh her down, silence her? Bend her. Break her?

Shanta Scott couldn’t make sense of the breakneck sequence of events. Her son had been killed the previous November in a shooting. Her job driving tourist buses in New Orleans was gone in March. The federal payments she used for her rent expired in July. Out of work and at home, she’d hear the occasional rustle of an apartment manager tucking a folded red piece of paper into her door frame.

All she had to keep up with her bills was the insurance money that came in after her 19-year-old son’s funeral. But it wasn’t enough.

“The bills keep rolling around,” said Scott, 41. “I still have to eat. I have to put the gas in the car. …I have to worry about keeping it together …. I have so much that I am doing right now to maintain, that I don’t have the proper time to grieve.”

Feed. Fight. Push, push, push. It’s the mantra she repeats to herself.

It’s also the mantra of a pandemic that has put many like Scott on the brink of financial ruin, despite protections the federal government has tried to roll out. And now, a tidal wave is coming: The last of those protections, a federal moratorium on evictions, is set to expire on January 31. This date is an extension from a previous year-end deadline that changed only after Congress passed a second stimulus package on December 20, less than two weeks before the moratorium would have lifted.

Women — already the most vulnerable to job loss, the most likely to be sole heads of households, the ones who are most often the sole providers for their children — are also the most likely to be evicted.

Even before 2020, Black women faced evictions at twice the rate of White people in at least 17 states, according to a study by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Sandra Park, senior attorney at the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, said it’s “unimaginable” to think about what communities will look like without broader policy in place to stop the looming mass evictions.

“Unfortunately, the fallout will be borne most by women of color who have also had to bear so much of the fallout of the pandemic and economic crisis overall,” Park said.

This year, the renters most likely to be behind on their payment are Black women, according to an analysis of U.S. census data by the National Women’s Law Center. About 30 percent are behind on rent — twice the rate of White men and women.

Eviction has lasting economic consequences, making it harder to find suitable housing in the future. It also has reproductive health and child welfare consequences: Children of mothers who face evictions are far more likely to live in substandard housing, leading to poor health outcomes.

An eviction in a pandemic adds another layer of complication, putting thousands at risk of being homeless or in shelters that are already overcrowded, where the ability to socially distance or quarantine is nearly nonexistent, said law professor Emily Benfer, who chairs the American Bar Association's COVID-19 Task Force Committee on Eviction, and is the principal investigator on a study of nationwide coronavirus eviction moratoriums and housing policies.

“It’s really this recipe for higher infection rates and death,” Benfer said.

But even with the recent $900 billion coronavirus stimulus plan — which includes $25 billion in rental assistance in addition to the eviction moratorium — only temporarily solves part of a problem. The current moratorium still allows landlords to begin filing evictions; it only blocks them from taking those cases to court, which they’ll be able to do again after the ban lifts. The cases are simply waiting to be addressed, and Scott fears hers could be one of them.

She was only able to keep her apartment after Southeast Louisiana Legal Services stepped in and paid her rent in September and October, and a nonprofit paid for most of her rent in November. She hasn’t paid December’s.

Scott has kept her son’s room, the only bedroom in her apartment, largely intact since his death. Next to his school medals, his football and baseball trophies, and his sneakers, are the cards friends and family sent and the T-shirts they wore when they laid him to rest. A bottle of cocoa butter lotion and deodorant was still sitting atop his dresser, right where he left it when he walked out of their home for the last time. A glass table in her living room holds his mellophone with an orange flower stuffed into its mouthpiece. Childhood photos, memorabilia buttons etched with his face, pictures from his senior prom — which was Grammy’s themed, fitting for the young musician — sit all around the apartment.

Her home isn’t just the place she lives. It’s her last physical tether to her son. Leaving it would mean tucking all she has left to remember him into boxes. If she does have to leave, she has thought, she’d sooner throw her own stuff away and live in her car with all of his things.

The grief and the fear of considering it is almost impossible to explain. It’s like screaming with every muscle in your throat, Scott said, but no sound comes out.

In April, when the economic impact of the pandemic was at its worst, 20.8 million workers lost their jobs. This happened amid a severe affordable housing shortage, where roughly the same number of renter households — 20.8 million, according to 2018 figures — were spending more than the recommended amount of their income on housing.

As the crisis has worn on, the recovery has slowed. More people left the workforce in November than the number who joined it.

That has put as many as 40 million renters at risk of eviction this year, according to an estimate by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, a policy advocacy group that reports annually on the nation’s affordable housing shortage.

When the pandemic started, a patchwork of eviction protection policies were enacted on the state and federal levels. Forty-three states and the District of Columbia instituted an eviction moratorium as early as March 13 and as late as April 30; seven states never implemented protections at all. Federal protections came at the end of March, when the CARES Act, or the first round of coronavirus stimulus, passed. It included a moratorium on evictions through July 24.

When that expired, some cities and states let their own eviction moratoriums lapse and were left without any sort of protections against evictions — until September 4, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stepped in and issued the block through the end of the year, citing the potential increase in the spread of COVID-19.

A University of California, Los Angeles, study — which has not yet been peer-reviewed — found that evictions led to more than 10,000 deaths from the coronavirus and over 400,000 cases. Before states lifted moratoriums, eviction-related COVID deaths on average remained flat. But researchers found that the more time states went without an eviction moratorium, the more related deaths increased. Within four months, states with a lapse in moratoriums had doubled the amount of eviction-related COVID spread. Deaths increased five-fold.

In Texas, which ended its statewide rent protections on May 18, the state experienced close to 150,000 COVID cases and nearly 4,500 deaths connected to eviction; by contrast, Pennsylvania, which kept its moratorium in place until the last day in August, saw no increases in cases or deaths due to evictions, according to the study. The study did not track individual evictions, but made correlations based on population sizes, COVID-19 spread and eviction rates.

Kathryn Leifheit, a researcher on the study, said that a lot of these evictions were focused in Black and Latinx neighborhoods and cities, where people have moved in with family and friends and spread the virus that way. Leifheit’s team published the study in late November before it was peer reviewed because the number of cases was rapidly increasing nationwide and the research team agreed that someone needed to make the link between eviction and COVID spread. She wanted it to be clear that eviction protections are a life raft.

“At a moment when we're seeing so many cases of COVID and so many deaths from COVID, you can imagine that the effects [of eviction] might be much larger and we might see many more cases and deaths associated with lifting that national moratorium,” she said.

While the second congressional stimulus package that passed in late December extends the moratorium, Sabriya Linton, another researcher on the UCLA study who also studies housing and race, said “band-aid approaches” can only be so helpful. Economic assistance and rent cancelation to help both tenants and landlords would be key, she says, especially in predominantly Black communities struggling with housing security and disproportionately high COVID-19 case numbers.

In those weeks between the CARES moratorium and the CDC’s stop-gap, Eviction Lab, a national eviction database, saw that the number of new eviction cases filed started trending upward in most of the 17 of the major cities it tracks.

Housing experts have been calling for additional rental aid in the form of stimulus payments, expanded unemployment insurance or other help that will solve the underlying problem: that months and months of rent is about to come due for people who have been unemployed long-term — a number that has grown throughout the pandemic.

Without rental assistance, the situation is untenable for some landlords, as well.

Paula Cino, vice president of construction development and land use policy at the National Multifamily Housing Council, which represents landlords, said many minority owners, typically small investors, are dealing with situations where a large number of their tenants, often half or more, are making partial payments or no payments at all. At stake is the potential loss of thousands of rental units that were being kept affordable by smaller operators.

A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia of households where people were working prior to the pandemic found that 1.3 million will be behind on rent by the end of this year, totalling $7.2 billion.

“What we have been stressing,” Cino said, “is that we can’t let what is now a public health crisis turn into a housing crisis.”

Racial discrimination in the nation’s housing practices has long been an issue — and one that has long disproportionately impacted Black women. The New Deal in the 1930s introduced redlining — the policy that marked Black and other minority neighborhoods as riskier for mortgages, blocking many people of color from access to stable housing — and also denied farm workers and domestic service workers, many of them Black women, from access to labor protections like minimum wage, overtime pay and collective bargaining rights.

This began a legacy of financial setback that, despite significant strides, still finds Black women earning 62 cents on the White male dollar.

The pandemic has only exacerbated this lopsided inequality. This year, unemployment among Black women hit 16.5 percent — the highest it’s been in almost 40 years — and the second-highest of any group behind only Latina women. The burden is compounded when you add children or dependents. Nearly 70 percent of Black women are the primary or only breadwinner in their family, according to a report from the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank.

At Southeast Louisiana Legal Services, the legal aid group that helped Scott with her rent, about 72 percent of the evictions cases they’re tracking are situations in which a woman is the head of household. The vast majority of them are Black women.

In Harrisonburg, Virginia, Winnette Dickerson lost her job in March. Soon after, she missed rent on the townhome her family has lived in for 13 years.

Dickerson knew the moratorium could protect her, but she ultimately took another, lower-paying job and cashed in all but $200 in her savings to move to another apartment. As a long-time volunteer in area homeless shelters, the image of what her life could become haunted her.

“The thought of joining them in the line, the people that I’ve been serving — that was very disheartening,” said Dickerson, 53. She said her multiple sclerosis has worsened after the stress of this year — there’s a weakness in her right side that wasn’t there before.

She also understands now more than ever how many barriers are stacked against people of color like her.

“Unfortunately, this is just part of being a Black woman in America,” she said.

When people lose or are at risk of losing their homes, the consequences pile up: Public health. Mental health. Domestic abuse. Child welfare.

All of those are on the line for the disproportionately high number of women and mothers who fail to make rent.

“Shelter-in-place orders and these sort of situations where folks are increasingly at home really does kind of set up the perfect storm in terms of the power and control and coercion that abusers can exert over survivors of domestic violence,” said Renee Williams, a senior staff attorney at the National Housing Law Project.

Economic instability has led many survivors to stay with their abusers, Williams said, beginning a cycle that repeats itself.

Researchers have long documented how Black women are disproportionately evicted following domestic violence calls to the police. In a 2012 study, Matthew Desmond, the founder of Eviction Lab, and sociologist Nicol Valdez examined the relationship between evictions and domestic violence.

Their study looked at every nuisance citation in Milwaukee over a two-year period. Properties generated such demerits following “excessive” police calls for anything from arson to noise complaints to littering. Black neighborhoods experienced them most often, with domestic violence contributing to a third of all citations. In response, the research found that Black women felt the brunt of evictions following those citations. Police can threaten landlords with fines, forfeiture or incarceration for being a so-called nuisance, so landlords often opted to evict the tenant, even if they were the victim of abuse.

“In poor Black neighborhoods, eviction is to women what incarceration is to men: a typical but severely consequential occurrence contributing to the reproduction of urban poverty,” Desmond and Valdez wrote.

For mothers with children, there are child welfare implications when they lose stable housing. Women with kids are more likely to face eviction than women without kids, according to a study by Harvard University. For children, eviction could disrupt education, splinter important developmental relationships and lead to mental health issues.

Being at the brink of those possibilities is crippling, something the pandemic has forced on Lakesha Barrett for the first time. The single mother of five has always been the person with more stability — the one her family has turned to for help.

But the coronavirus has infected her life. Two of her children got it and recovered. Her two-year-old grandson got sick, too. Her older brother is in the hospital with it. So is her grandmother. Her aunt died of it, as did three patients who Barrett worked with every day at an assisted living facility in North Carolina.

Barrett lives with three of her kids in public housing, a dilapidated apartment with water damage, peeling paint, cracks in the bathtub and an unstable foundation. She said she’s called to have the doors fixed, at least, but they remain broken. She said she called, too, in July when her hours dwindled from few to zero at work, and she tried to have her rent readjusted to account for the lost income. But months of calls and emails and attempts have been futile, she says. She’s now six months behind on rent.

Barrett knows eviction could come next if a solution doesn’t materialize. But she has nowhere to go if it doesn’t. She hasn’t told her kids.

“I’m trying to keep it,” she said. “It’s all my kids have.”

In the fight for eviction protection, grassroots organizers and housing attorneys are doing whatever they can to stop cases from having to go to court, though in some places, they already have. During the pandemic, landlords have filed more than 162,000 evictions in 27 cities, Eviction Lab found, with the most filings in New York, Phoenix, Houston, Memphis and Fort Worth, Texas. And more cases are already in line to be processed depending on what the Biden-Harris administration decides when the extended federal eviction moratorium ends on January 31.

In Ohio, some courts have started using convention centers to process eviction claims and keep people socially distanced. Other states have gone to Zoom court, and the new format has introduced its own set of problems, including too few translators for non-English speakers, technology challenges and a widening information gap for tenants.

In Louisiana, Southeast Louisiana Legal Services attorneys have been going to court in person, taking COVID-19 tests every week. The number of eviction cases they’re handling is up 300 percent from last year.

Even with the moratorium, which only protects renters in cases where they miss payments, landlords have tried to evict people for other reasons, like too many people in one apartment or too much noise — issues that could be directly tied to the pandemic, said Laura Tuggle, director of Southeast Louisiana Legal Services.

And the CDC moratorium itself is not on autopilot. The onus is on tenants to submit a declaration to their landlord swearing that they’ve tried to obtain government assistance for rent or housing, earn less than $99,000 as a single person or $198,000 jointly, and lost income through layoffs or out-of-pocket medical expenses. Qualifying tenants must also promise under threat of perjury that without the moratorium, they would likely become homeless and that they are making efforts to make partial payments.

Landlords do not have to inform tenants about the declaration, and may also challenge the truthfulness of a tenant’s declaration in court.The CDC moratorium only stops evictions on the grounds of nonpayment; tenants can be put out if accused of damaging the property or violating building and health codes.

Nicole Paluzzi, a pro bono housing attorney in Charleston, South Carolina, estimates that seven out of ten times, her clients are women between the ages of 40 and 60, single with at least one child under the age of 18, and almost every one is Black. Among large cities in the United States, Eviction Lab ranked North Charleston as home to the most evictions per capita, with about 10 households put out every day.

Because Paluzzi’s child is medically vulnerable, she attends eviction hearings remotely. However, not all tenants can pay for stable internet or the technology that allows them to join hearings online. She reflected on a “heartbreaker of a case” involving a woman in her 50s, whose former spouse injured her so severely she’s under a conservatorship after suffering brain damage that makes it difficult to form new memories. When her landlord was diagnosed with cancer, the house she lived in for several years went up for sale. Ultimately, Paluzzi’s client was displaced following an end-of-lease term eviction. The ordeal played out over Zoom.

“It's heartbreaking as an attorney because you can't be there to support your client when they're getting that bad news,” Paluzzi said.

In Missouri, one of seven states that has gone the entire pandemic without an eviction moratorium at the state level, Kansas City organizers chained themselves to the doors of a downtown courthouse in protest of Circuit Court Judge David Byrn, who let a moratorium in Jackson County, which contains part of Kansas City, lapse on May 31. Landlords started taking tenants to court again, despite the CARES Act’s federal eviction moratorium in place at the time.

KC Tenants, a non-profit composed of tenants in Kansas City, counted more than 1,700 eviction filings after the local ban was lifted, according to an October report. In the three days in September between the CDC’s announcement of an upcoming moratorium and its enactment, landlords in Jackson County filed hundreds of eviction filings.

The judge, Byrn, then issued a court order that said in part that landlords and property owners could still proceed with evictions as long as they file a “verification form” with the court that asked landlords to tick a corresponding box for their reason for evicting a tenant.

Tara Raghuveer, founding director of KC Tenants, worked with the ACLU to file a lawsuit in September against Byrn and his court administrator, citing the ACLU’s research that found Missouri to be one of the states where landlords file against Black women double the rate of White people. A federal judge has since denied their request for a preliminary injunction, but a final ruling on the lawsuit is still pending.

“We were never under any illusion that a broken court system was going to deliver us justice — this is a tool in our belt,” Raghuveer said of the lawsuit. “We're also pretty clear that this system that's oppressing us is not going to be the one that is going to liberate us, which is why we didn't stop any of the direct action while we were suing the judge.”

Apart from the demonstrations, KC Tenants has joined virtual eviction hearings where organizers interrupted judges’ proceedings to support tenants at risk of losing their homes. Raghuveer estimates they’ve delayed upwards of 300 eviction hearings through physical and virtual disruptions in addition to providing at-risk tenants with the CDC declaration materials.

But now, Raghuveer says they are preparing for what happens when the federal moratoriums expire for good and the delayed hearings are on the docket again.

Looking to the future Biden-Harris administration, Raghuveer hopes to see the federal government avoid a 2008 housing crisis, and prioritize acquiring foreclosed properties to hold them off the private market and develop an ambitious social housing program instead. The nation already had millions unhoused before the pandemic made millions more housing insecure — people will need permanent places to live to rebuild their lives, she said.

Raghuveer isn’t alone. A report from The Justice Collaborative, a progressive think tank, makes the case that President-elect Joe Biden should go after a New Deal-like reform and focus on expanding public housing to also attack climate and energy crises, the racial wealth gap and housing insecurity.

In the interim, organizations are looking to support their own communities. The fundraising platform GoFundMe dedicated a portion of its website to help renters navigate asking for assistance. In New Orleans, a group is crowdsourcing donations for a rental assistance fund for more than 44,000 New Orleanians impacted by the loss of weekly federal unemployment benefits. The fundraiser has collected more than $79,000 of its $100,000 goal.

The insecurity is what keeps Scott on edge in New Orleans.

She was on the road to stability before all of this happened. When her son started college in June 2018, she enrolled in school, too, at Stevenson Academy of Hair Design.

The two of them were doing well — they had a plan. Jacé was a talented musician. He had attended Talladega College in Alabama on a music scholarship to play the mellophone. When he came back to New Orleans, he started recording music.

That’s where he was headed on November 24, 2019, poking his head out of the window of the car on a crisp night as Scott watched him pull out of the driveway with some friends.

The police reports later said Jacé and a friend had been play-fighting with guns until the friend got scared and shot. The bullet pierced Jacé’s neck.

In her apartment that night, Scott woke up. The dream had been so vivid. A vision of a church. A casket. A man asking about insurance.

Her pain has been suspended since that night. In its place, a singular focus: To keep moving forward, to achieve the things she told Jacé she would.

She recently got rid of her bed that she had set up in the would-be dining room. She refuses to sleep in Jacé’s lush bed — she said she doesn’t want to get too comfortable at night when she has work to do. So she lays her head on one of her orange leather couches in eyesight of her vision boards with her goals for 2020.

Get up. Pray. Talk to Jacé. Exercise. Stop smoking “cigs” — check, cold turkey. Work to get the bread — in progress.

In the now-emptied dining room, she practices hairstyles on mannequin heads, as a life-size cardboard cutout of her son stands watch. Scott wears two sets of earrings, a pair of gold studded “J’s”, and a dangling set with the name of her late son written in cursive, the other lobe featuring the name of his Jacé’s late father, who was shot and killed in 2007.

Earlier this month, Scott graduated from the hair academy. Since she lost her job, she’s applied to at least 80 positions by her count. She recently landed a job as a school bus driver, but she won’t see a paycheck until she completes training. Being around other people’s kids is painful, but the rent eats first.

The rent. The room. Jacé’s Talladega College hoodie strewn across his tightly made platform bed. The threat of eviction, more of those red slips now stuffed in kitchen drawers. The thought of his things in boxes. Of acknowledging what happened.

“My son’s spirit is still there,” she said. “I’m dealing with his room still there. I’m dealing with overwhelming bills. I have to deal with it every day — every night.”