We’re the only newsroom dedicated to writing about gender, politics and policy. Subscribe to our newsletter today.

In the most consequential election many Americans will ever live through, the idea of “electability” has loomed large.

During the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, six women sought to challenge the idea of electability, that indefinable quality that makes people believe a candidate is most likely to win a race. Ultimately, voters landed on choosing between two septuagenarian White men to lead the country for the next four years.

This Election Day, electability will not be about defining a candidate’s attributes, but rather, defining the electorate’s actions.

In 2020, women will decide who is electable.

Women make up the majority of the U.S. population, the majority of the workforce and the majority of the electorate. Yet less than a quarter of the seats in Congress are held by women. Only 7 percent of state legislators are women of color. There has never been a woman president of the United States. And for just the third time in history, voters have an opportunity to make a woman the vice president.

The past four years have marked an era in which women have shaped, and been shaped by, American politics.

In 2016, Democrat Hillary Clinton became the first woman to win the nomination of a major political party, but in the general election, despite winning the popular vote — receiving more votes than any candidate in the history of the Democratic Party — she fell short of becoming America’s first woman president in the Electoral College.

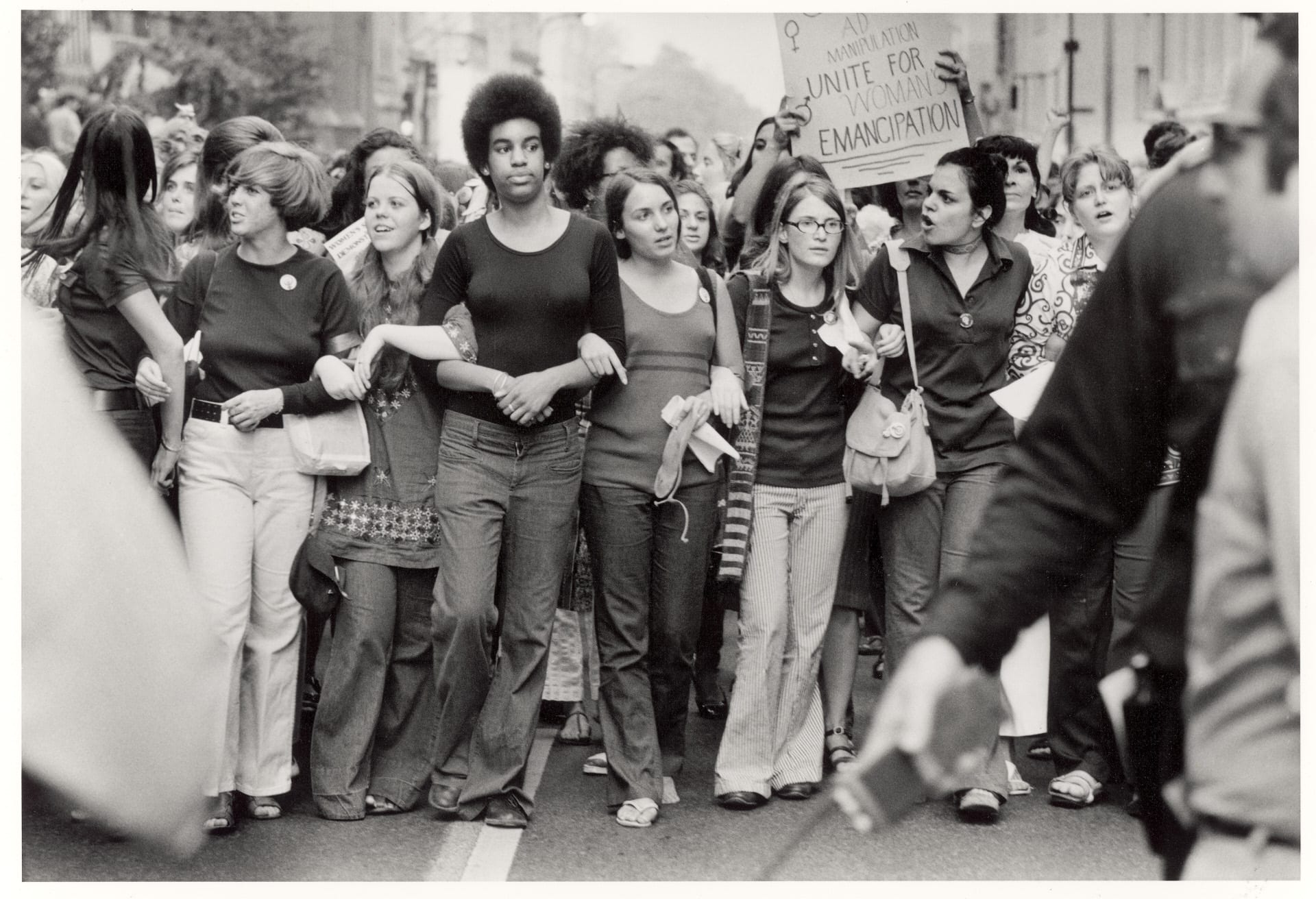

President Donald Trump’s victory unleashed anger and frustration among many women, culminating on the day after his inauguration in 2017 at the Women’s March, the largest single-day protest in U.S. history. The rally was initially conceived of by White women, but its agenda was shaped by and carried out largely by women of color.

Later that year, the #MeToo movement, started in 2006 by Tarana Burke, went viral as allegations of sexual harassment and assault against prominent men in media, entertainment and politics prompted survivors from across the country and around the world to share their stories and call for accountability and reforms.

Women’s political energy fueled the 2018 midterm elections, which saw record turnout for an off-presidential year, leading to 25 women U.S. senators and 102 women in the U.S. House — resulting in the most diverse Congress in American history.

The reckonings over systemic racial injustice and sexual violence against women are also political, and on the minds of women headed into the ballot box this year. Women’s activism and protest have continued, over issues including family separations and the nomination and confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

The result has been a coalition of White women and women of color who, largely in response to the rhetoric and policies of President Trump, are mostly voting Democratic.

“After 2016, there was a feeling among a lot of women that no one was coming to save us — not a party, not a candidate — that if we were going to actually build the powerful forces we needed to change what’s happening in this country, we needed to do hardcore self-reflection and organizing,” said Supermajority co-founder Cecile Richards.

“Women have been the activists, the phone bankers, the door knockers, the donors, the candidates and the voters,” she continued. “It’s not any subgroup; it is women writ large, led by women of color, as a force that’s going to change our fortunes on Tuesday. In many ways, the suffrage movement and its very troubled history has been an opportunity to learn from the mistakes of the past that we can never repeat.”

It’s “Trump with a capital ‘T’” who has driven the political action of many women since 2016, said Betsy Fischer Martin, executive director of the Women and Politics Institute at American University.

“Four years ago, women saw [the president’s] conduct during the campaign, but were willing to dismiss it or rationalize it, focusing on what he was going to do and wearing that red Republican jersey,” Martin said. “In the interim, you’ve seen women wake up to the fact that you can’t rationalize it because you’ve got the rhetoric, tone and his actual performance over the past four years.”

And then, 2020 happened.

This has been a year when women’s issues have been pushed to the fore of the country’s consciousness. Though the majority of deaths from COVID-19 have been men, women have borne the economic, mental health and caregiving impacts of the virus.

More than 865,000 women dropped out of the workforce in September alone during the country’s first female recession, unable to balance work and caregiving. Women have lost more than half the jobs in the pandemic, and Latina unemployment is at an all-time high.

“People are earning less money for the same work,” said Ai-jen Poo, director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA). “The economic reality right now is that the workers who lost their jobs and income and have been just struggling to put food on the table, keep the lights on and keep a roof over their heads … are dealing with all kinds of challenges that are falling on the shoulders of the people who have the least amount of power.”

In the final days ahead of the election, there has been no more urgent issue than the pandemic for women, whose election priorities were already health care and the economy. Recent polling has shown that likely voters who are women overwhelmingly trust former vice president and 2020 Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden to handle the response to coronavirus rather than Trump. Some Democratic-leaning women expressed outrage at the president’s own COVID-19 diagnosis in the final stages of the campaign.

“Women are trying to take care of their own families, and then they look up and see a president making fun of people who wear masks, holding these rallies,” Martin said. “There’s a big disconnect there.”

As a result, many women have been galvanized to cast their ballots and mobilize other women in states critical to the election to do the same. Of the nearly 100 million early votes already cast this cycle, more than half came from women in battleground states like Arizona, Florida, Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina and Texas.

“The creativity, the energy, the momentum is literally palpable,” said Poo, who noted NDWA volunteers have sent more than 6 million text messages to voters in key states. “We’re natural organizers and we’ve been using these skills we’ve developed to make sure we are organizing all of our networks.”

And this drive to the ballot box is happening against the backdrop of the centennial of women’s suffrage and the 55-year anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, two legislative feats that feel threatened — especially for Black and Brown women — amid concerns of voter suppression.

Women’s shared concerns have helped fuel a sense of shared fate across racial, geographic and economic lines, in many cases for the first time, said Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza.

“The last four years have been marked by women coming together and embracing our power,” said Garza. “This is … about the intersection between where folks are concentrated in the economy, what we’re experiencing in relationship to systemic racism and inequality, and the attacks on health care.”

Latina women, many of whom are essential workers coming home to multigenerational households vulnerable to coronavirus, are also poised to make a statement this year as a significant voting bloc motivated by the pandemic and the president’s rhetoric, said Maria Teresa Kumar, founder of Voto Latino.

“When [the president] was talking about Mexicans not sending our very best, he was talking about our husbands, our brothers, our sons. We took it very personally,” she said. “I want him to know it was young Latinas who stood up and fought against what his expectations were of us.”

The future of American politics will be decidedly female beyond 2020 — and possibly decidedly Democratic, said Morley Winograd, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute. Winograd declared earlier this year, along with political scientist Michael Hais, that “the gender realignment of American politics is the biggest change in party affiliation since the movement by loyal Democratic voters to the GOP in the “solid South” half a century ago.

“This is not a one-night stand; this is a permanent affiliation with the Democratic Party, and it doesn’t depend on women being the candidate,” said Winograd. “That’s really new and powerful. You can’t gerrymander women out of a district. This is really the most profound change in American politics in the last 50 years, and it isn’t over. We’re going to see a big impact [on Election Day], but it’s just the middle of this change.”

Both parties should understand that the ultimate definition of electability is about who women elect, that this constituency can no longer be treated as a special interest group — and women should not allow themselves to be treated as such either, said Supermajority’s Richards.

“The more women understand this and can really lean into that power, that’s when we can not only be the deciders at election time, but we can hold government accountable on the many issues that fall to the bottom of the list,” she said. “The election isn’t the end. That’s the day the door opens.”