We’re the only newsroom dedicated to writing about gender, politics and policy. Subscribe to our newsletter today.

“Excitement” does not even begin to capture Inez Brown’s feelings about Kamala Harris’ historic win. Brown, 55, was initiated into Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., at Howard University with Harris in the spring of 1986.

“I am incredibly proud of my line sister, friend, dedicated public servant and skilled politician, Vice President-elect Kamala Harris,” Brown said in an email to The 19th. “Her win is symbolic of hope for America, and serves to inspire every girl, teenager, young woman and grown woman to greatness.”

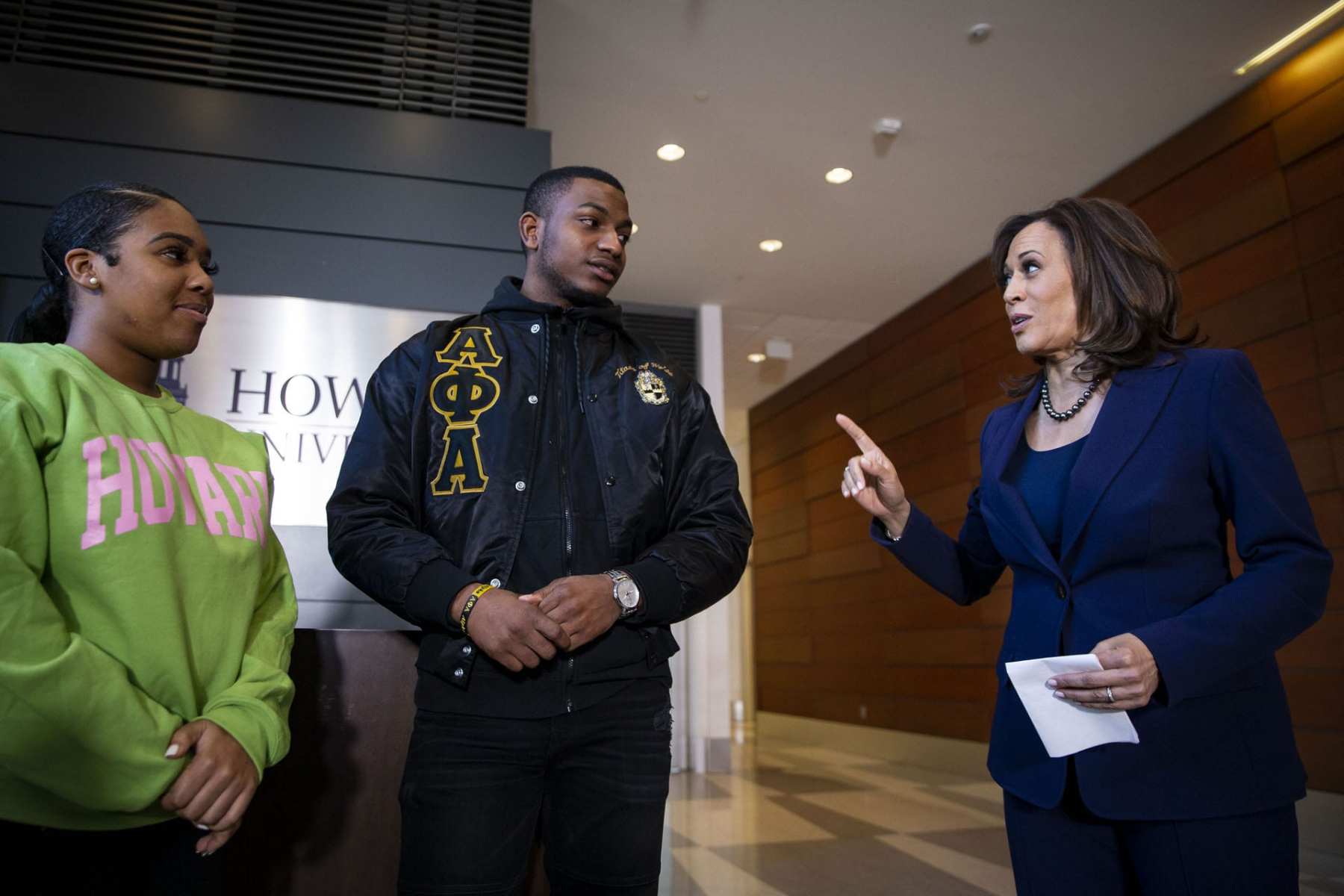

Harris, the first woman of color to be vice president, represents another milestone: She will be the first graduate of a historically Black university in the White House. Harris made her Howard University education a central part of both her own campaign for president and her time on the ticket with Biden. In accepting the vice presidential nomination, she nodded to her “HBCU brothers and sisters,” counting them as “family.”

Gabrielle Horton was working through her hangups with Harris when the senator became the Democratic Party’s nominee for vice president in August. Horton felt connected to Harris: Like her, Horton is a Black woman from California who chose a HBCU. Horton went to Spelman College in Atlanta and the vice president-elect graduated from Howard University in Washington, D.C., in 1986.

Still, Horton was concerned about Harris and Biden’s records on crime and law enforcement. But she is thankful that President Donald J. Trump will be limited to a single term.

“I’m still a Black girl from LA, who went to Spelman, who was brought into politics by the late Rep. John Lewis, so of course I’m in a mode of celebration,” Horton said. “We know the work continues. But I’m not there right now. Today, I’m enjoying Saturday.”

It’s difficult to describe the experience of an HBCU education. How do you convey what it feels like to come of age in the same dormitories and classrooms built to educate the formerly enslaved? Or to find your lifelong friends out of shared interests rather than as a way to survive four years as the overwhelming minority in White institutions built with slave labor? For many, matriculating through an HBCU marks the first and only opportunity to establish a multi-hyphenate identity outside of a racial caste system.

Branda Johnson, 28, wanted to attend an HBCU for as long as she could remember. But as she shared this dream with her peers in her hometown of Boston, no one understood why she would want to go to “one of those schools,” she said in a text.

“I remember people telling me I was making the wrong decision … and even asking silly, stupid questions like, ‘Did they even have classrooms.’”

She went to Hampton University in Virginia anyway, majoring in public relations. Harris making it to the White House makes her think back to all of those people who told her she was making a mistake — even if Harris attended “the other HU,” Johnson said, referring to the rivalry between Johnson’s alma mater and Harris’.

Often, HBCUs are not seen as models of the real world. How will graduates fare when brushing shoulders with White people once more? Horton is among the HBCU graduates who hope Harris’ rise puts such opinions to rest.

“We know what’s possible among us,” Horton said. “It’s cool that everybody is trying to catch up now. We knew what we had to offer. We knew the heights we were reaching all that time. People were just discounting us because we didn’t go to [predominantly White institutions] — what does that even mean?”

Three years ago, Trump shared a photo of him signing an executive order with dozens of HBCU college presidents surrounding his desk in the Oval Office. The Presidential Executive Order on the White House Initiative to Promote Excellence and Innovation at Historically Black Colleges and Universities effectively established a board of advisors for HBCUs. Throughout his presidency, Trump claimed he “saved” HBCUs, particularly after he signed the FUTURE Act in 2019, which automatically renewed federal funding for HBCUs, rather than going to Congress for approval each year. However, he did not increase funding noticeably compared to the Obama administration.

On the campaign trail, Biden and Harris promised to make HBCU funding a priority through funding an expansion of their digital infrastructure and issuing $18 billion in grants to make the schools more affordable for students.

As a current college student at Clark Atlanta University, an HBCU in Atlanta, Miranda Perez is relieved that she will be graduating into a Biden administration. She was a high school senior when Trump was elected, and decided she wasn’t comfortable going to a predominately White school during his presidency. Clark Atlanta’s motto — “Find a way or make one” — resonated with her as a Puerto Rican and first-generation college student, and she really liked the school’s mass communication program. She says attending the school was the best decision she’s ever made in her adult life.

The 21-year-old was in her room doing some homework when, one by one, her group chats for various classes started exploding with reactions to the election.

Perez is not visibly Black, and she’s encountered people who say she should reject that identity. But she doesn’t. Being at an HBCU, she’s had to defend her choice to attend a Black school, but she’s found a community among Caribbean and Latinx students.

Harris, the child of Jamaican and Indian immigrants, has also faced criticisms for not being “Black enough.” But Blackness isn’t a monolith, Perez said. She finds that a similar thing happened to President Barack Obama, who is biracial. But Obama is a man, Perez noted, who could cut his hair into a low-fade and avoid some of the backlash that comes along with being a light-skinned Black woman with straightened hair.

Perez does not question that a Black woman who chose Howard (coined “the Mecca”), and was initiated into Alpha Kappa Alpha’s first chapter, has Black interests at heart.

“In all of [Harris’] pictures at Howard she had a ‘fro,” Perez said. “Why would she go above and beyond to attend an HBCU for undergrad, stay involved in Black organizations to get into office and suddenly she’s not Black enough because she’s light skinned? Or because she’s multicultural and biracial, however people want to break it down?”

Brittany Foxhall, a Howard alumna and member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., felt that Harris’ ethnicity contributed to “a multi-pronged win.” It was a testament to the power of on-the-ground organizing, the power of the Black vote and how important it will be to see Harris in office, she said.

“It’s not just about her being a Black woman. It’s about her being more than that, the intersectionality of who she is,” she said. “It reaches far beyond just the Black community. But then on top of that, as an HBCU grad, it’s like we all feel seen. It legitimizes our experiences and our choices in deciding to get a degree from an HBCU.”

Foxhall wants to see HBCU support rolled into an agenda for Black America within the first 100 days of the Biden-Harris administration that also touches on police reform and financial and educational improvements. It’s only right, she said, considering that cities with Black strongholds ushered them into the White House.

Foxhall, who was poring over her law school coursework when her group chats started lighting up that the race had been called, has been questioned about her decision to attend Howard. People have said that an HBCU education won’t take her to the same places a White school would. No one can say that now with Harris in office, Foxhall said.

“It’s high time to recognize and acknowledge that HBCUs are producing the Black middle class. They are producing the majority of judges, politicians, doctors and lawyers and they deserve the acknowledgement in terms of what these institutions mean to furthering our people and not just within our community but in the country as a whole.”

Jazmine Freeman, 22, was in the middle of filling out her FAFSA for the upcoming school year when she saw the breaking news on Twitter. She screamed, laughed, cried a little and called her mother immediately. Both mother and daughter are members of Alpha Kappa Alpha. The two started planning what kind of new custom sorority gear they would have made for inauguration as her mother “skee-wee’d” on the phone, employing the sorority’s greeting call.

“It’s so hard to really say how I feel about this, because it’s just so mind-boggling,” Freeman said. “I can’t believe it. People are going to be discussing this election for the rest of their lives.”

As Freeman processed the news, she felt more anxious as people took to the Atlanta streets, honking their horns. She thought about the White militia groups who might also be there.

Unsurprising to Horton, a Spelman alumna, there is another HBCU graduate capturing headlines: fellow Spelman alumna Stacey Abrams. Although the votes in Georgia are still being counted, the state is on the verge of going blue for the first time since Bill Clinton ran for office in the 1990s. Horton is thinking of the Black women and queer organizers — “masterminds,” Horton branded them — who’ve been getting out the vote both quietly and ferociously, including Abrams.

After losing the Georgia governor’s race to Brian Kemp by less than 55,00 votes, Abrams started Fair Fight Action, taking the battle against voter suppression to 18 states. She has been widely credited as a driving force behind Georgia being in play for the Democrats this year.

“I am thrilled to see the way in which people have been supporting Stacey Abrams. I think in many ways she is the face of the many Black women and Black organizers that we’ll never know the names of, or hopefully we’ll get to know more about in the days to come,” Horton said. “But [Abrams] in so many ways embodies a lot of the work that’s been happening across the South. Of course a good Spelman woman had to help us deliver this. I’m just happy to see that. It makes me proud to be a product of Spelman.”