Kandice Ortega cleaned the tables and phones in building 503 with a sanitary pad. There were no fresh rags, but she didn’t want to live in filth — cleanliness had taken on a new, pressing importance.

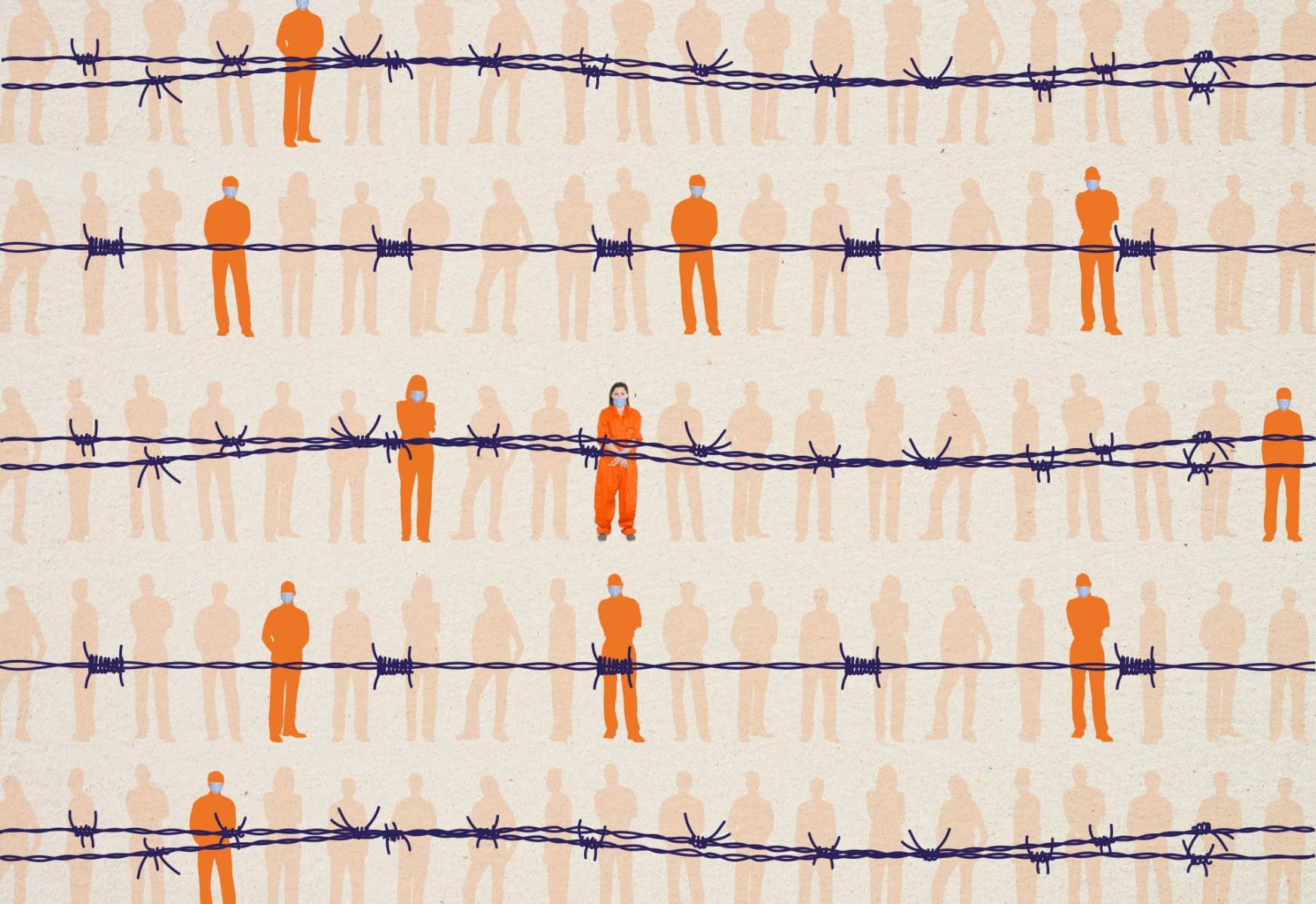

Like many, Ortega worried about getting COVID-19. But unlike much of the country, Ortega had few options to limit her exposure. She is incarcerated at the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF), the largest women’s prison in the world.

When CCWF officials began to limit activities and movement to safeguard against the coronavirus, building 503 was turned into a quarantine unit with 100 beds for isolation. Ortega was moved to 503 after her roommate tested positive for COVID in mid-July.

Ortega, however, said she never tested positive for the coronavirus. And after multiple negative COVID tests, she said she remained in the quarantine unit for weeks.

As she wiped down surfaces, Ortega couldn’t shake the feeling that cleaning the building she shared with COVID patients would inevitably infect her too. Would it come from the air vents? The seldom cleaned showers? The guards?

When the second-shift correctional officer came to check her cell for contraband, Ortega said he rummaged through her things without a face covering. She suspected that he was wearing the same gloves he wore among COVID patients. She was uncomfortable, but refusing searches could have led to disciplinary repercussions like losing her spot in the honor dorm, and possibly standing before the Board of Prisons to explain why she disobeyed a direct order from a correctional officer.

“On the streets they are asking for you not to have people over your house and to social distance,” Ortega said in an email to The 19th. “I am not given a choice in here. I am not allowed to say no.”

So, Ortega, out of options, did the only thing she could to keep the virus at bay: She unfolded menstrual products and started to clean.

“I am forced to make a choice on what’s more important, my freedom or my health,” Ortega said.

Via email, The 19th interviewed nine people incarcerated at CCWF. Eight of them told The 19th that CCWF was holding prisoners who had tested negative for the virus in 503, quarantining people who were COVID-19 negative in close proximity to those who had the virus. The ninth discussed lack of safety related to the virus in the prison but did not reference building 503.

Nearly half of the people interviewed live with pre-existing conditions — asthma, heart conditions, a compromised immune system — that put them at heightened risk for complications of COVID-19. All described dirty, unsafe conditions that left them wondering if their lives will end in prison.

In mid-August, after The 19th submitted questions to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) about its alleged practice of housing COVID-positive and negative people together, those incarcerated inside CCWF said administrators began sending people who had tested negative back to their assigned housing. All of the people The 19th interviewed are now out of 503. Lt. Gene Norman, a public information officer for the department, denied that people who had negative COVID tests were ever housed among sick people.

“When an inmate’s test [sic] have returned negative, they are released back into general population housing,” Norman said.

CDCR also maintains that it is following safety protocols, denying that prisoners are living in dirty or dangerous situations or that guards have not been wearing proper protective equipment like masks.

But in emails to The 19th, people who lived in 503 told a different story.

The coronavirus has rocked prisons nationwide. According to data from Oct. 9, in addition to 16 incarcerated people who’ve contracted the virus at CCWF, there have been 45 confirmed cases among the prison’s staff, and one death. Nearly 15,000 people incarcerated in California’s prison system had confirmed COVID-19 cases — the fourth-highest number of cases behind prisons in Texas, Florida and the entire federal system, according to an analysis by the Marshall Project and the Associated Press. All this comes despite early warnings from public health officials, who cautioned that prisons could become petri dishes for the disease.

In April, amid outbreaks, California released approximately 3,500 people serving non-violent sentences. And in July, more than 5,000 people with less than a year to serve were slated for release to “decompress the population to maximize space for physical distancing, and isolation/quarantine efforts.” This summer, California’s incarcerated population dropped below 100,000 for the first time in 30 years.

But people incarcerated at CCWF do not feel like the people in charge of their livelihood — guards, prison officials, all the way up to the governor’s office — have done enough to protect them.

In a July 28 letter to California Gov. Gavin Newsom, Elizabeth Lozano wrote that she was forced to attend a drug re-entry program that exposed her to the virus. (Newsom’s office did not respond to The 19th’s request for comment.)

“I understand we are in a pandemic however the way we were exposed is not OK,” she wrote. “I’m a mother hoping to one day be with my family, I’ve worked very hard on my rehabilitation to be treated as if I’m not human.”

Lozano thinks she was exposed sometime during the week of July 15, when CCWF resumed the Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment (ISUDT) program. At the time, the prison had suspended most other programs and jobs because of the pandemic. Lozano and others claim it was nonessential.

“It was mandatory to show up. We had to sign contracts. If we didn’t go, it was a disciplinary action which meant we would lose our date to go home,” Lozano said.

One ISUDT staff member exposed 38 prisoners to the virus, Lozano claims. Those 38 had contact with the entire yard — 650 prisoners. Lozano, who was among those directly exposed, was sent to building 503.

Between July 24 and August 19, three of CCWF’s four buildings were placed on a “modified program,” which limited movement in the building, according to Terry Thornton, deputy press secretary for CDCR. Thornton declined to speak to the source of the virus in CCWF or explicitly weigh in on the ISUDT program. Thornton told The 19th that in-person programming was being closely monitored, and could be paused or stopped at any time.

Lozano, 45, suffers from asthma, lupus, neuropathy, a heart condition and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, an inflammatory lung disease that makes it hard to breathe. She tested negative for COVID-19 three times in two weeks, but continued to be kept in the isolation unit. She said she was forced to use the same showers, breathe the same recycled air, touch the same surfaces and come into close contact with prisoners who had COVID-19 and the staff who had contact with them.

“I stopped showering in the showers completely out of fear,” Lozano wrote in an email. “Every day in this 503 building is a day of anxiety and fear, not just me but my peers who also are terrified of getting sick and death.”

Lozano has been eligible for parole since February 2019, according to state records. In August, her family launched a petition requesting her release.

It included a plea from her brother Richard: “Please don’t let this be a sentence where it will cost her life and never have a chance to be a mom to her son or experience a second chance at life.”

In response to the COVID-19 outbreak in San Quentin Prison outside of San Francisco, which has claimed 28 lives as of Oct. 9, the Amend program at University of California San Francisco and Berkeley’s School of Public Health issued an urgent public memo with recommendations to curb the spread of the disease. Among the strategies included were providing better ventilation through air-conditioning systems and opening doors and windows as much as possible, which has been proven to decrease the transmission of COVID-19.

“Note that the important aspect is air exchange, not the movement of air within the room,” the memo reads. “Fans that blow air around may help cool people, but they don’t decrease rebreathing aerosols unless they filter the air or increase air exchange.”

Those suggestions seemed to change little at 503.

When she was in 503, 32-year-old Laura Purviance spent all but two hours of the day in her cell — quarantine felt similar to solitary confinement, she told The 19th. Purviance claimed she was kept in 503 despite never receiving a COVID-19 test.

While there, Purviance noticed leaking pipes and partially collapsed sections of the ceiling, which she believed is because of a ventilation system in disrepair. In the hot prison, people were not wearing their masks appropriately, she said. She did her best to keep her distance, so despite the disciplinary risk, she packed up her meals, avoiding the cafeteria where there is “no physical distancing” and no place to wash or sanitize hands before meals.

“Staff continues to not wear masks nor physically distance themselves,” Purviance said in an email. “Some of my peers have asked their families to take out life insurance policies on us, that’s how unsafe it is to be in here with this pandemic going on.”

Prison officials told The 19th there are no issues with the ventilation system and no collapsed sections of the ceiling, “partially or otherwise” and that prisoners receive 90 minutes a day for telephone calls, laundry, showers, cell cleaning and other activities.

Purviance, though, is not the only person at CCWF who complained about faulty ventilation. Outside of 503, Stacey Dyer told The 19th that the ventilation system is so spotty that she and her four roommates — who all work cleaning hospital areas alongside prison staff — rely on fans. Dyer fears the fans make germs more capable of spreading around the hot room. It’s hard to find relief in the 90-degree, 25-square-foot room Dyer and her roommates share.

“We live, sleep, breathe the same air constantly,” Dyer said. “There is no such thing as social distancing in prison. It’s impossible.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long asked prisons to space people out, and at minimum have people sleep head-to-foot. But Dyer’s “bunkie” sleeps so close to her she can touch her arm while laying in bed.

“We are afraid because we know that it is only a matter of time before the COVID is spread, infecting every single woman here,” Dyer said.

For a month, Mychal Concepcion went without standing in the sun.

“I got to walk to the clinic because I had to get my T shot, and I had to do that twice,” he said on a phone call in early August, referring to his dose of testosterone. “That’s the only time I’ve been outside.”

Concepcion is a 50-year-old-transgender man who has spent 22 years in this women’s prison. California has the largest transgender prison population in the country, with 1,203 trans people incarcerated as of February 2019. Overwhelmingly, prisoners are housed according to their gender assigned at birth, like Concepcion, who estimates there are 30 to 40 trans men incarcerated at CCWF.

On July 24, Concepcion went into quarantine in 503. That meant no time in the yard to exercise, even though he has never contracted the virus. Now, he is back in his old cell after testing negative four times. He gets one hour every other day in the yard.

On other days, he prays, meditates and exercises in his room.

“I got to jog the other day when the air quality was a little better, I am grateful for that,” he wrote in an email. “All the smoke from the various fires was just sitting in this valley.”

The pandemic has been especially stressful for many trans people in prison. The virus has severely strained prison workforces across the nation, and in many cases reduced or cut off access to medical care. In June, trans prisoners at San Quentin started reporting that no one was getting gender-confirming hormone treatments.

In a letter obtained by The 19th, an administrator confirms that over the July 4 weekend, staff noticed that some hormone treatments had been delayed.

“San Quentin State Prison (SQ) recently experienced severe, short-term nursing staffing shortages due to an outbreak of COVID-19 among employees and patients,” the letter states, adding that the pandemic further strained nurses that were on the clock.

The following week, people on the outside alerted administrators to the fact that hormones were not being prescribed.

Although administrators said that the hiccup was due to extreme staffing shortages, trans prisoners claimed something more sinister: hormones had been deemed medically unnecessary by San Quentin staff during the pandemic.

Thornton, the spokesperson for the department, said that delay was due to staffing issues alone and that “audits showed there were no missed medications for patients at SQ who wished to accept them.”

Concepcion said that he did not have an interruption in getting his hormone therapy, but the virus has exacerbated power dynamics in the prison. Because he is trans, staff treat him like he’s disposable, he said, like it doesn’t matter if he contracts the virus. Staff misgender and demean him.

“I am an inmate, murderer, gang member, want-to-be man, offender, convict, and all the other names they call me under their breath or in their minds that I don’t hear,” he wrote. “Since I am not human it wouldn’t matter if I got it and died.”

One man, who asked only to be identified as Ashley, said his dorm room houses eight people, including him. Ashley is 31 and has asthma, and he said he can’t get supplies to keep himself safe. While the state allots each prisoner two bars of soap a month, it’s not enough during the pandemic, Ashley said. His family sends him money to buy extra soap. He doesn’t have any hand sanitizer.

“The staff is getting sick and not reporting it and still want to come to work,” he said.

He was tested for COVID-19, but never got the results back, he said.

The CDC has asked prisons and detention centers to provide free soap to incarcerated people. Many prisons and jails ban hand sanitizer for its alcohol content, despite the CDC asking institutions to consider relaxing these restrictions.

Norman, the CDCR spokesperson, paints a different picture of life inside CCWF. He said prisoners are given sanitizer and soap and that staff can request additional supplies throughout the month, if needed.

“Every housing unit receives normal monthly supplies of cleaning materials which include hospital-grade disinfectants, window cleaner, sanitizers, hard surface disinfectant wipes and other cleaning products and all CDCR institutions conduct deep-cleaning efforts in day rooms, showers and living areas,” he wrote in an email.

The pandemic has dramatically changed life for people like Ashley, who returned from court in March to a seven-person dorm and “modified program,” a limited lockdown due to the virus.

“We come out for an hour a day to use the phones and do laundry,” he said. “Every other day we can go outside for an hour by one hallway at a time.”

It took six COVID-19 tests, all of them negative, to get Ortega out of 503. She’s back in the honor dorm, but the weeks of quarantine stick with her.

“I am having a hard time adjusting since I’ve been back,” she wrote. “I’m not sleeping at all, I’m not really eating. I have a lot of anxiety and fear of getting sick or having to go back to 503 and live in those conditions.”

Ortega is not alone. After re-integrating into the general population, others shared lasting impacts of quarantine with The 19th.Concepcion has witnessed “a lot of signs of trauma” among those who’ve returned from 503. Lozano has seen a clinician a few times for PTSD since leaving 503 on Aug. 19.

“After being treated the way we were in 503 all of us have trauma and are like shell shock,” Lozano wrote in an email. “We’re experiencing trouble sleeping, anxiety, trouble eating and like waiting for something bad to happen. I think that’s from knowing that at any moment we can be housed there again.”

And still, some say guards are maskless and in groups. Several people reported that guards are searching people as they exit the chow hall, making sure they didn’t take food out with them. And there’s no social distancing in a pat down. The fear — of getting the virus, landing back in 503 — is ever present.

“God forbid you bring out your eggs from breakfast,” Ortega wrote. “It’s as if security has been breached.”