Corvo Leung doesn’t have a plan for November.

In the last week of July, the 24-year-old looked up the voter registration requirements for Washington, D.C.

“My ID currently has my name that I was given at birth along with the gender that I was given at birth, neither of which I am now,” they said.

Leung, who is genderqueer and doesn’t fit into the binary of male or female genders, was in the middle of a legal name change when the pandemic shuttered the D.C. Superior Court in March. Their April court date got pushed to June 25 before it was postponed indefinitely. They haven’t heard from the court since.

Leung, who moved to D.C. from California, needs to register to vote in their new city. D.C. doesn’t have strict voter ID laws, and Leung can register to vote using a bank statement or utility bill. They hope that means they won’t face obstacles at the polls, even if they can’t get an updated ID by November. Still, every time that Leung has pulled up the registration application, they face a new question.

“I’m still a little unclear as to which name to put while in the middle of the process,” they said.

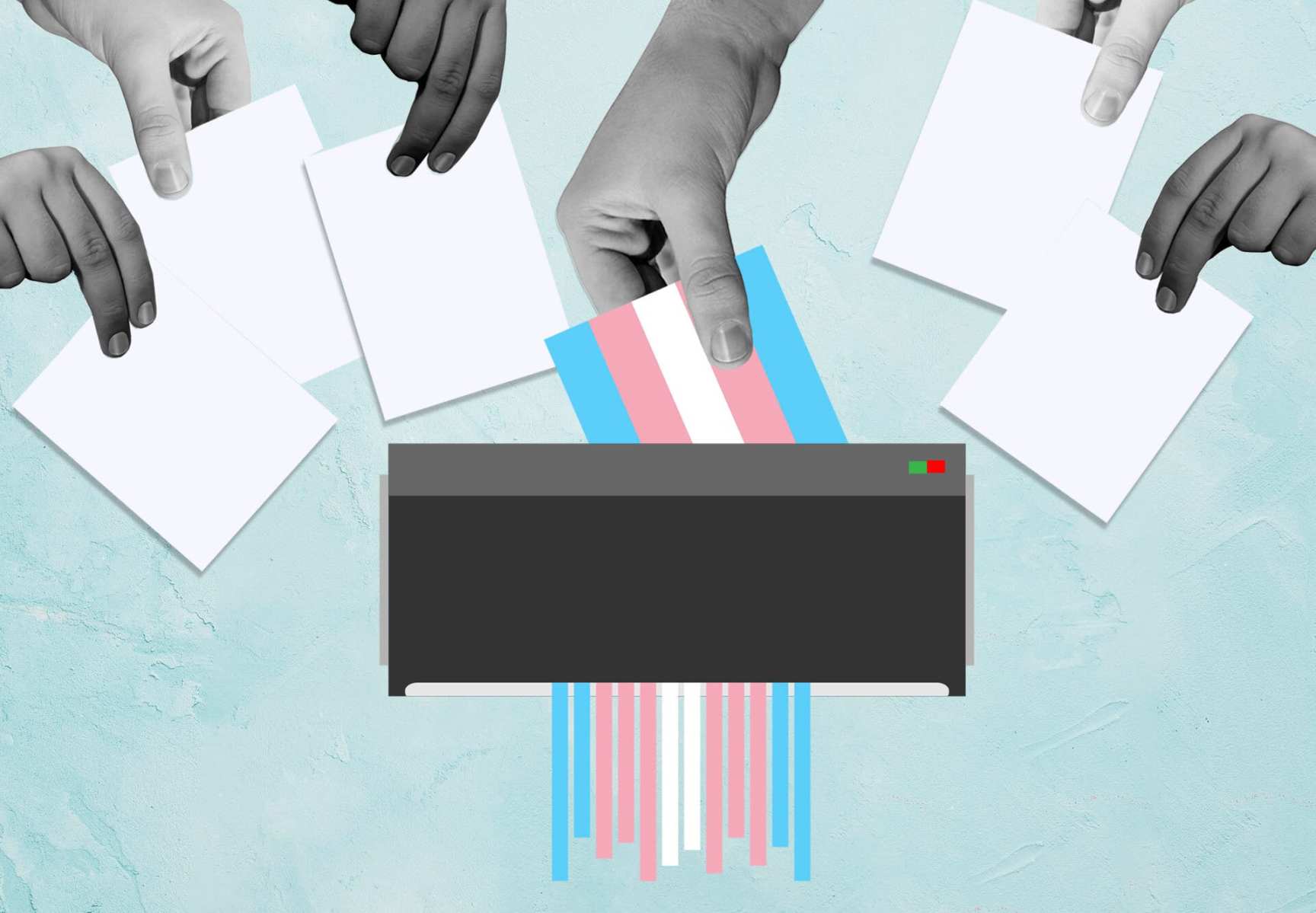

Hundreds of thousands of transgender voters will face similar hurdles this election season, advocates say. Even before coronavirus closed courts and DMVs across the country, trans voters faced the prospect of disenfranchisement in November; 35 states have voter ID laws on the books requiring voters to bring some form of identification with them to the polls.

Now, in many states, updating legal name and gender changes — one of the largest obstacles to voting for trans people — has become impossible.

Arli Christian, campaign strategist for the ACLU, has worked with several states and the federal government on updating ID policies to make them more trans-friendly.

“It’s hard to go in and get legal name changes,” said Christian. “Some people who are in the middle of the process of updating identification documents may have gotten stuck there, because agencies are closed … all of those barriers make it even harder for trans people during this pandemic to get their vote in.”

The problem with voting while trans

In February, before coronavirus locked down much of the country, the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law reported that 42 percent of eligible trans voters — 378,450 people — could be barred from casting a ballot in November because of ID laws. That’s because 46 percent of trans people don’t have identification that lists their correct name and gender, according to the National Center for Transgender Equality.

Christian attributes that reality to the many hurdles trans people face in obtaining a legal name change or gender marker update.

“It often means that trans people have to go in front of a judge to get a legal name change, that a trans person may have to go to various different types of medical providers to get documentation of who they are,” Christian said. “So it’s an expensive, confusing, burdensome process.”

She thought my name was fake.

Sade Viscaria

In 2018, a poll worker in Burlington, Vermont, refused to give a ballot to Sade Viscaria, a trans woman. Viscaria wanted to cast a ballot for the United States’ first transgender gubernatorial candidate on a major-party ticket, Christine Hallquist. Vermont doesn’t have restrictive voter ID laws (only first-time voters need to show ID), but the poll worker didn’t believe that Viscaria was female, as her ID indicated, and refused to issue her a ballot.

“She discriminated against me for being transgender and [accused] me of having a fake ID,” Viscaria said in 2018. “She thought my name was fake.”

Viscaria voted later in the day at another polling location, but the incident spurred a statewide investigation and national fears about trans voting access.

Those fears have prompted local and national LGBTQ+ organizations to encourage voters to arm themselves with backup identification and phone numbers for legal organizations on Election Day. Two years ago, the National Center for Transgender Equality Action Fund launched an website dedicated to combatting transgender voter disenfranchisement. The site offers a one-page checklist for trans voters on how to prepare for voting and a trans voter hotline.

Even in progressive California, long hailed as a beacon of trans inclusion, officials have expressed concerns over trans voter disenfranchisement. LGBTQ+ organization Equality California and Secretary of State Alex Padilla launched a statewide plan last year that requires all California poll workers to undergo training in accommodating transgender voters.

“Every eligible voter has a right to cast a ballot free from any unnecessary burdens or intimidation,” Padilla in a statement, noting that even though California law doesn’t require photo ID for voting, trans voters remain at risk of being turned away if their legal name doesn’t match their gender presentation.

Jody Herman, author of the Williams Institute study, said the pandemic presented an opportunity to make it easier for trans Americans to vote.

“If states increase access to voting by mail, that would be a benefit to trans voters, since they would not have to interact with poll workers or election officials if they vote by mail rather than at the polls,” Herman said.

Herman’s report estimates that 965,350 transgender adults will be eligible to vote in the 2020 elections — 892,400 trans people reside in states that historically don’t vote by mail. As coronavirus pushes more states to adopt mail-in voting, some trans people will be able to escape the scrutiny of poll workers trying to gauge their gender presentation against their gender markers.

However, of the 35 states with voter ID laws, 14 still don’t allow voting by mail without justification.

California policy now favors allowing a person to vote even if their gender presentation is incongruent with their ID or name. California, however, is the exception, not the rule. Although the pandemic has made voting more difficult for everyone, many trans people face the prospect of losing their voting rights.

The complication of Covid-19

Brianna Blackburn counts herself lucky in the mess of name changes during COVID-19. She filed for a legal name change in New Jersey in February, and even though her April court date was cancelled, she was still able to update her name in July.

“It was pretty easy, actually,” she said. “I did it all myself.”

Blackburn got in line the first day her local DMV reopened and waited with hundreds of other people from 3:00 a.m. until 9:00 a.m. when they opened.

“I was in the Army, so a lot of things were hurry up and wait,” she said. “I’m used to waiting. That didn’t really bother me.”

Other people are likely to have a much tougher time, experts say.

It is virtually impossible to update social security cards and passports right now because most offices are shut down.

Kanoa Arteaga

Kanoa Arteaga is the microgrants program director at Trans Lifeline, a crisis hotline for transgender people. He oversees a detailed database on the processes and fees for name and gender marker changes in every state and county. His organization distributes small grants to help trans people fund the costs of name and gender marker changes.

“The barriers that trans folks are facing right now are very much institutional,” Arteaga said. Those challenges have become “particularly perilous” during the pandemic, as complicated processes have become confusing or altogether unmanageable, he said.

In March, Trans Lifeline saw traffic to their grants page, which contains the database on ID changes by state, quadruple. In July, the site had 10 times its usual traffic. To advocates, that spike signals that trans people are running into barriers as they navigate name and gender change processes.

After transgender people complete a legal name change, the next obstacle is updating government issued identification cards. In many states, that can’t be done without amending a social security card, another system that has been upended by the pandemic.

“It is virtually impossible to update social security cards and passports right now because most offices are shut down,” Arteaga notes.

And at least 14 states also require that the applicant prove they have irreversibly changed gender by providing a doctor’s certification. In other words, a transgender person has to undergo surgery in order to vote.

“That’s a huge barrier,” said Christian. “It means that a good chunk of trans people are not able to go ahead and get updated documentation.”

Gender-related surgeries can range in cost from $15,000 to $100,000 for the uninsured, and many insurance companies do not cover the procedures. For those that do, the costs still generally top $600.

Gender-confirming surgeries for trans and nonbinary people who want them are not just a matter of fulfilling bureaucratic requirements. The American Medical Association has deemed gender-affirming healthcare as medically necessarily and essential in treating gender dysphoria.

Those procedures, however, have also been impacted by the pandemic.

“What I know is that those surgery dates are either being held in limbo or they’re being postponed indefinitely,” said Arteaga. “And so we’re sort of beholden to the same systems of gatekeeping resources to trans folks that are potentially life-saving.”

Not every transgender person wants to medically transition. Although trans people experience their bodies in myriad ways, some transition-related medical care can also cause infertility. That leaves many trans people unable to update their documents and, thus, unable to vote.

Since 2017, a growing number of states have adopted gender-neutral IDs, with “X” gender markers. Nineteen states and Washington, D.C., where Leung lives, issue IDs with the designation. Leung is eager to have an “X.”

“I was just like tasting the freedom of having my identity documents reflect who I actually am,” Leung said. That, like a lot of things, will have to wait.

Christian, who has helped many states adopt nonbinary IDs, also warns voters with nonbinary IDs might face confusion at the ballot.

“Many of these states have implemented an ‘X’ designation; however it’s available on their state ID, but it’s not available in other places,” Christian said. Notably, not all voter registrations reflect that their states issue nonbinary IDs.

“It’s not a legal problem, and you should not get in trouble for that,” they said. “However, it can cause administrative confusion and complication. It may cause an agent that you’re working with to question who you are … It’s unnecessary scrutiny to trans folks.”

The stakes have never been higher

LGBTQ+ advocates have stated outright that the outcome of the presidential election may be a matter of life and death for many, particularly for trans people of color.

On Monday, a day before it was set to go into effect, a federal judge halted a Trump administration rule that would have stripped health care protections for trans and nonbinary people from the Affordable Care Act. Trump administration policies have also aimed to dismantle transgender protections in schools, homeless shelters and employment.

Even before the pandemic hit, nearly a third of trans Americans lived in poverty and faced unemployment at three times the national rate, according to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. As the pandemic has left millions jobless, transgender people have been particularly hard-hit. When the general unemployment rate spiked at 14.7 percent in April, 19 percent of trans people reported losing their jobs, Human Rights Campaign reported.

In October 2018, The New York Times reported that the Trump administration had circulated a memo that defined gender as “immutable” and determined by genitalia at birth. For transgender, nonbinary and intersex Americans, that definition legally “defined them out of existence,” the Times noted.

This year is on track to be the most deadly for trans people ever recorded, with 26 transgender people already slain. Advocates say that crushing job losses, discrimination in housing and limited employment opportunities have forced many trans Americans into underground economies where they might face violence.

The Trump administration has fueled that crisis by breeding bias against trans people and then shutting down critical resources that protect them, advocates say. The National Center for Transgender Equality branded this “The Discrimination Administration.”

Trump’s apparent animosity for LGBTQ+ people seems to have ignited queer voter participation. NBC News reported that one in 10 super Tuesday voters identified as LGBT, a sharp jump from 2018 midterm elections, when LGBT voters made up 6 percent of the electorate.

How many of those voters fall under the “T” remains to be seen. Herman says that given the pandemic, it’s uncertain now how many trans voters will face disenfranchisement.

For five years, Blackburn voted in New Jersey under a name that didn’t fit her.

“It’s a little confusing for the people that are taking a vote,” she said. “But I think it’s been more confusing over the years since I’ve been on hormones and looking a lot more feminine than I used to.”

Now that her name has been updated, she doesn’t have to worry about the reaction she will get from a poll worker who is confused about her gender. When she got her new ID in July, she stared at it for a week. She already has her plan in place for November.

“I’m going to vote in person,” she said. She doesn’t mind waiting in line.