In the 2018 midterm elections, a historic number of women candidates drove the Democratic takeover of the U.S. House of Representatives. Heading into the 2020 elections, Republican women aimed to make it a bipartisan affair.

By some metrics, they have already succeeded.

There will be at least 243 women on U.S. House ballots across the country in November, including at least 74 Republican women, shattering the previous record of 53 Republican women set in 2004, according to the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) at Rutgers University. Some states have yet to hold primary elections delayed due to coronavirus, so these numbers will likely grow between now and November.

But there are political headwinds working against many of these Republican women. The nonpartisan Cook Political Report forecasts that Democrats will hold onto the House in November, and many of the Republican women are in districts where backlash to President Donald Trump led to historic Democratic gains in the House in 2018.

In at least 39 races, Republican women will be competing against Democratic women, setting a new record, according to CAWP data.

“The good news for Republicans is that they have recruited a record number of female candidates, it’s almost whiplash from what we saw in 2018,” said the Cook Political Report’s David Wasserman, who analyzes House races.

“The bad news is that most of these Republican women are unlikely to win,” he added.

There were 227 Republican women who filed to run for House seats in 2020, up from 120 in 2018. Just 52 Republican women made it onto general election ballots that year, compared to the 182 Democratic women (356 filed), who fueled their party’s House takeover that November, CAWP data shows.

The Republican lineup this year is reminiscent of the slate of Democratic women who broke barriers in 2018, when the first Muslim women and first Native American women were elected to Congress.

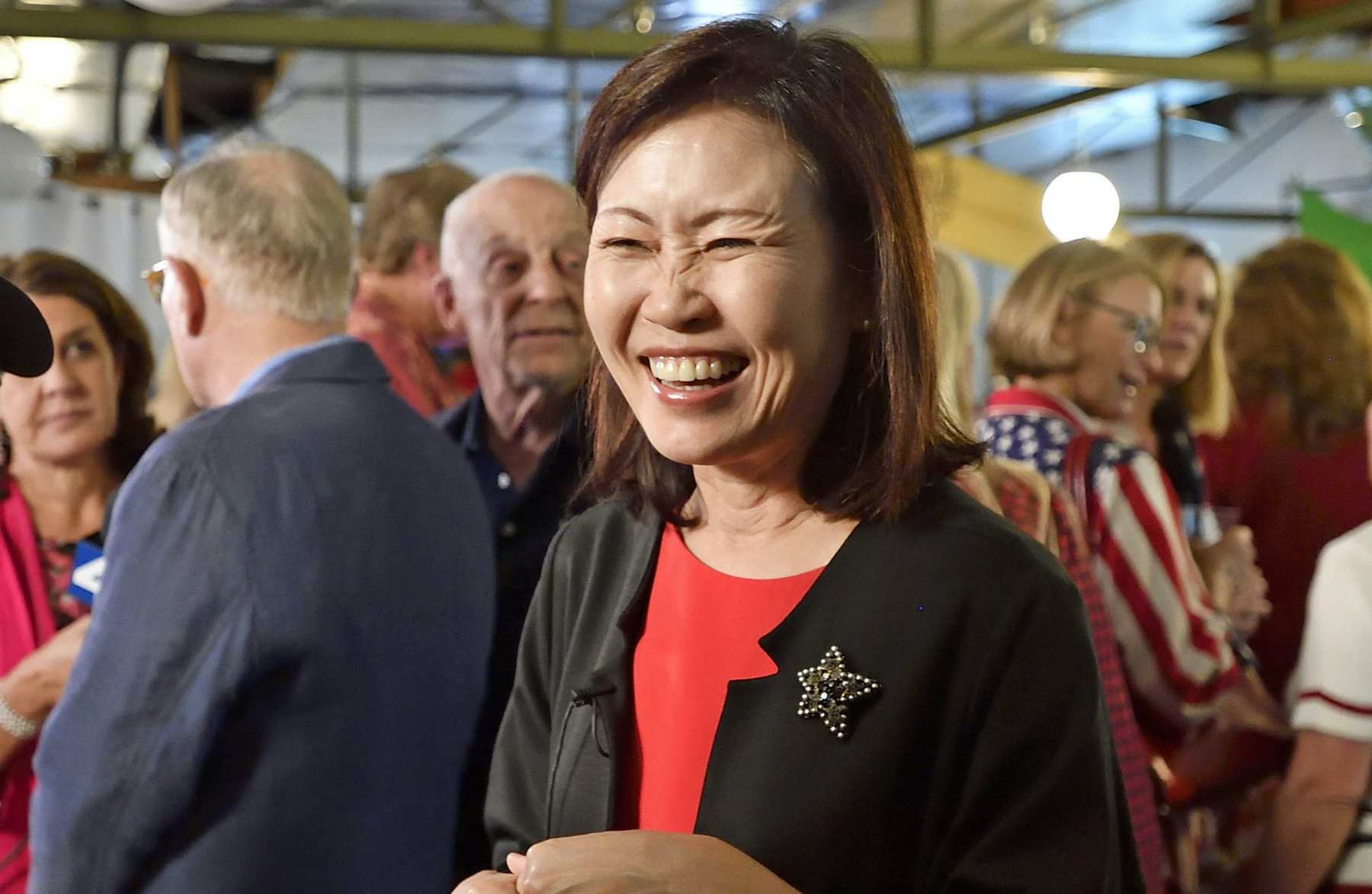

Among the Republican women who will be on House ballots this November are two candidates in Southern California — Michelle Steel and Young Kim — who would be the first Korean-American women elected to the House. Nancy Mace in South Carolina would be the first Republican woman to represent her state. Roughly a third are women of color.

Michael McAdams, spokesperson for the National Republican Congressional Committee, the arm of the party that supports House candidates, said: “In some of the most competitive seats across the country, House Republicans have strong female candidates.”

In the 28 races the Cook Political Report rates as “pure tossups,” there will be at least 10 Republican women candidates (and possibly more after states finish primary voting). This top tier of competitive races includes 15 seats currently held by Democrats and 11 currently held by Republicans.

Close races are also expected in 30 House districts currently represented by Democrats that Trump won in 2016, and in six districts currently represented by Republicans that Clinton won in 2016. (Some of these are also ranked as pure tossups.)

Of the Republican women who have won their primaries so far, roughly half will be competing in districts that are rated “solidly Democratic,” making their chances even slimmer, said CAWP’s Kelly Dittmar.

Dittmar believes that a contributing factor in this year’s surge in Republican women candidates are organizations that encouraged them to run for office after the 2018 elections, when their numbers in the House dwindled to 13. It was a wake-up call that prompted some to address the “historic disparity” in the support infrastructure for women in the two political parties.

“There was a lot more available to Democratic women in terms of training, targeted recruitment programs and financial support,” Dittmar said.

Shortly after just one new Republican woman was elected to the House in 2018, Rep. Elise Stefanik launched E-PAC to support top Republian women in their primary races. Stefanik was previously recruitment chair for the NRCC and though she recruited a record 100 women to run, many struggled to make it past their primaries, when the national party typically remains neutral.

There are currently 18 women on the NRCC’s roster of 36 candidates who have met metrics to be in their “Young Gun” program, which affords candidates access to additional support.

Previously, in late 2017, a group of strategists and donors founded Winning for Women, the Republican answer to EMILY’s List, which backs Democratic women who support abortion access.

Dittmar said the “extent to which these organizations and some individuals in the Republican Party identified the underrepresentation of Republican women as a problem in need of a solution” likely bolstered the ranks of Republican women filing to run in 2020.

But even Democrats have yet to achieve parity in the 435-seat House, where there are 101 women total, including 88 Democrats and 13 Republicans. That means women make up less than a quarter of the chamber, 38 percent of the Democratic Caucus and 7 percent of the House Republican Conference.

After Republican Rep. Ted Yoho called Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez a “fucking bitch” on the Capitol steps last month, reporters asked House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy whether Yoho’s insult — and a party meeting in which Republican men attacked Rep. Liz Cheney, the highest-ranking female House Republican, over her criticism of Trump — meant the party had a “woman problem.” McCarthy pointed to the record number of female candidates this year.

“There are more women running in the Republican Party for Congress than at any time in the history of this party. The record was 143, we’re well over 220. So if you want to measure it based upon that, I think we’re improving,” he said.

Local race, national dynamics

The House race in Indiana’s 5th District encapsulates many of the dynamics playing out in races across the country this year.

Republican Rep. Susan Brooks, who was first elected to the seat in 2012, announced in January 2019 that she would not seek re-election. Brooks, like Stefanik, has served as NRCC recruitment chair. Two women, Republican Victoria Spartz and Democrat Christina Hale, will be competing in November for her soon-to-be open seat.

Republicans have represented the 5th District since the early 1990s. Though Brooks won by nearly 14 points in 2018, the Cook Political Report has given it progressively more competitive ratings since she announced her retirement. The 5th District is now among the 26 races considered pure tossups.

The 5th District includes the north side of Indianapolis along with suburbs to the east and north such as Carmel, Nobelsville and Fishers. It is more than 80 percent White. More than 45 percent of its residents older than 25 years have at least an undergraduate college degree. It is the wealthiest congressional district in Indiana with a median annual household income of about $80,000, according to Census data.

Although they come from opposite sides of the political aisle, in a parallel universe with less partisan rancor, it does not take much imagination to picture Spartz and Hale working together to find common ground where they could legislate.

Spartz is a state senator. Hale is a former state representative. Both fought in crowded primaries and prevailed. In recent interviews, they both spoke of their commitment to work in a bipartisan manner and said they are running for the same reason: health care.

Spartz emigrated from the Ukraine after meeting her now husband on a train more than 20 years ago. She says she has seen firsthand the dangers of socialized medicine and believes individuals, not lawmakers, should make health care decisions. Her work on health care legislation in the Indiana Senate — in February the chamber approved a bill that would study changing Indiana’s Medicaid program to a block grant, among other provisions — made her realize she wanted to run for federal office.

Spartz prefers limited government. She wants pricing transparency in health care, thinks there would be more innovation if some CDC and FDA regulations were relaxed and believes that addressing the coronavirus pandemic could provide opportunities to test creative solutions such as telehealth.

“After working on that, and realizing that 85 percent of health care is controlled on the federal level, I thought about it and decided I needed to make my case,” Spartz said.

Spartz is a certified public accountant who has worked in “big four” firms handling the accounts of Fortune 500 companies. She has operated several businesses, including in the farming and real estate sector, along with her husband. She said she believes women bring “long-term thinking” to policymaking and may make “better long-term decisions.”

“When I worked in corporate America, we assessed the risk of companies, and if we had a CEO or CFO who was female, we would consider it to be less risky,” Spartz said.

Hale is a lifelong Indiana resident who worked her way through college while raising her now adult son as a single mother. She worked for the nonprofit Kiwanis International before becoming the second Latina elected to the Indiana General Assembly. In 2016, she joined Democrat John Gregg’s gubernatorial ticket as his pick for lieutenant but he lost to Republican Eric Holcomb in the same year that Trump won the state.

“After 2016, I couldn’t sit on the sidelines, I knew I had to stand up and do something about it, and so I got into this race,” Hale said.

“It’s the same reason why I ran for office the first time: looking around our state and talking to the people that live here, health care is a truly desperate need,” she said.

“I was a teenager when I got pregnant and I’m trying to raise this little kid and do right by him, and I just managed to ensure that he had health insurance but I didn’t always have coverage. For many years, I had no coverage, and it was really scary,” Hale added.

Hale supports the creation of a public option for individuals without private health insurance and greater transparency in prescription drug pricing. She noted that 20 counties in Indiana do not have an OB-GYN to provide critical health care.

Hale said in the statehouse she specialized in protecting vulnerable populations, particularly children, from sexual violence. As a freshman legislator she was able to find common ground with Republican State Rep. Ben Smaltz, who now chairs the party’s policy committee, to pass legislation that defined serious sexual offenses against minors that would result in a lifetime ban from being on school property.

“I find if you develop personal and professional trust with colleagues in your party, but most importantly across the aisle, that’s certainly how I got things done in the statehouse, and that’s what I want to do in Washington,” she said.