Eugene Robinson recovered from his double mastectomy on a hospital porch in Durham, North Carolina. It was August 1956, and as a Black child in the Jim Crow South, Robinson wasn’t allowed to heal next to White patients.

Sarah Robinson, Eugene’s mother, brought a daughter to the hospital. She returned home with a son. It was his third of four surgeries. Two of his nine siblings had undergone similar operations, but his relatives never talked about the fact that androgen insensitivity syndrome, a genetic intersex condition, ran in the family.

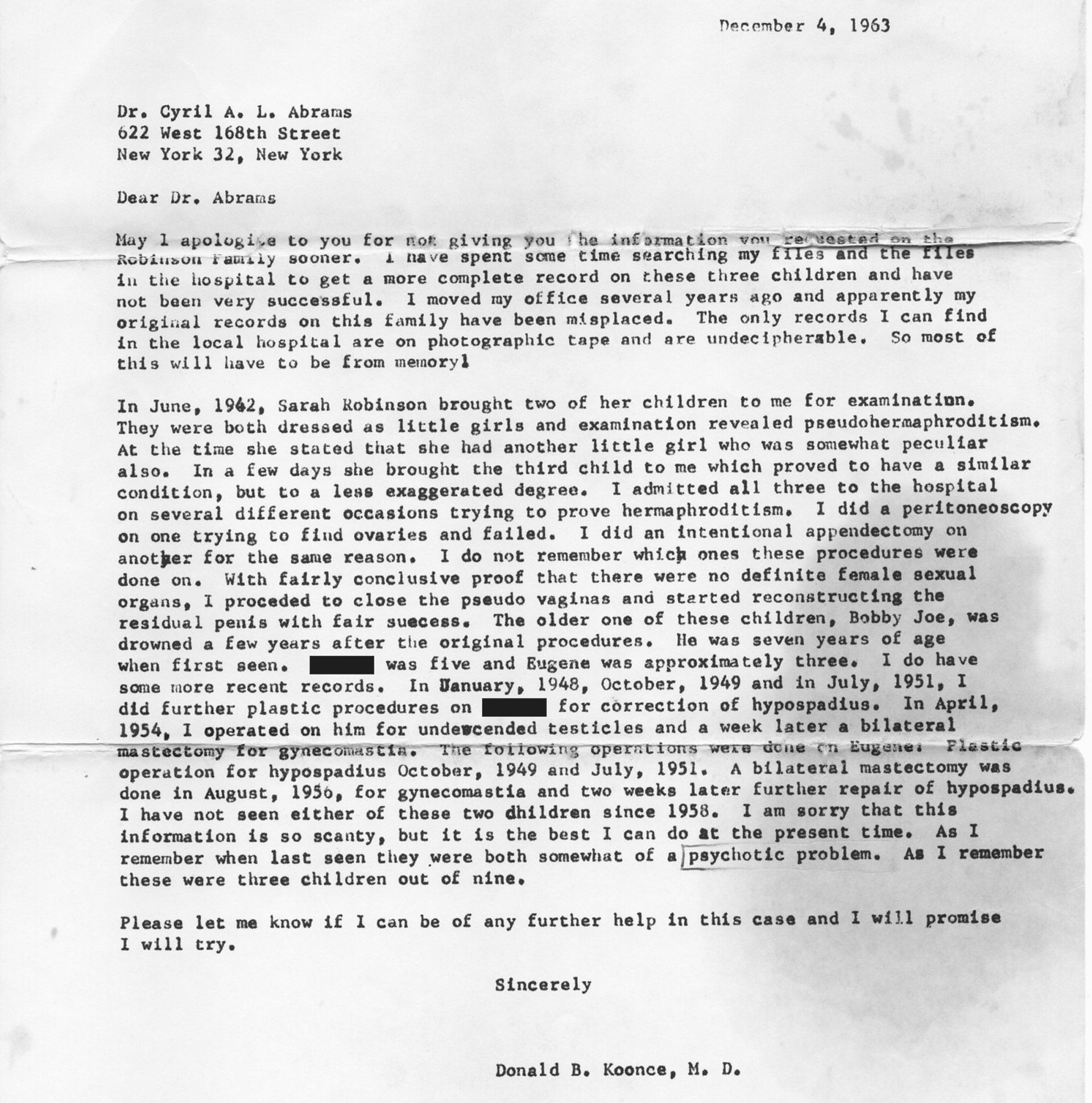

Nearly 65 years later, Sean Saifa Wall, 41, sifts through Robinson’s medical records, looking for answers about his uncle’s story that might shed light on his own. Wall, like Robinson, is intersex.

Intersex is an umbrella term for people with variations in sex characteristics that don’t fit neatly in the binary of male or female. Some intersex people are born with varying reproductive anatomy or sex traits — some develop them later in life. About 1.7 percent of people are born intersex, according to a 2000 report by Dr. Anne Fausto-Sterling.

Since the 1960s, medical convention has been that intersex variations should be “corrected,” often through a combination of painful surgeries and hormone therapy starting from infancy or before a child can consent. But on July 28, the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago became the first hospital in the United States to suspend the operations. The news comes after a three-year campaign against the hospital led by Wall and Pidgeon Pagonis, co-founders of the Intersex Justice Project.

Activists have been protesting intersex surgeries since 1996, when a group demonstrated outside the American Academy of Pediatrics’ convention in Boston. Since then, the UN has condemned the surgeries — which remain legal in almost every country in the world — as “irreversible” and unnecessary procedures that can cause “permanent infertility and lifelong pain, incontinence, loss of sexual sensation, and mental suffering.”

Wall knows that pain intimately.

Wall came out as gay at age 14. Then, he came out as transgender. In both cases, his mom “lost it,” he said. “She was like, ‘why do you want to wear men’s clothes, men’s underwear?’”

But Wall’s oldest aunt reminded his mom about his intersex uncle, now deceased. His aunt said “‘do you not remember playing with Queen Esther as a child?’”

“And my mom was like, ‘Who’s that?’ And she’s like “‘That’s Gene.’”

Wall says the memory “blew my mom’s mind” — for seven years she had a sister. Looking back, she did remember Esther.

Eight of his family members were intersex, Wall says. The more that Wall started to talk about himself, the more his family opened up about their own histories.

Up until the time he was 13, Wall’s mom resisted doctors’ insistence that he have surgery to remove undescended testes, he says. She saw his older intersex siblings suffer through their own operations and thought they were unnecessary.

“They told my mom that the testes were cancerous,” Wall said. So his mom agreed to the surgery. Wall never had cancer.

He had spent two years under the care of a doctor that he says studied him, asking him questions about whether or not hormones made him less gay. Still, it wasn’t until college, while doing a Yahoo internet search, that Wall pieced together that he is intersex.

“I was so angry,” he said. “I was like, ‘Oh, this is not fair. It’s not right. I didn’t talk about it for a while. I would tell people here and there, but I didn’t talk about it publicly because I had so much shame.”

When he was 25, he started taking testosterone, something he wanted to do as a trans person to confirm his gender. But he wasn’t metabolizing the testosterone the way most people on the hormone do.

I would tell people here and there, but I didn’t talk about it publicly because I had so much shame.

Sean Saifa Wall

“I think I felt really suicidal,” he said, referring to people constantly misgendering him. “But I knew that if I took my own life, that no one would ever know what happened to me, and no one would ever know my side of the story.”

That’s when Wall decided to start organizing for intersex rights.

For 19 years, Lurie patient Pidgeon Pagonis also believed they had survived ovarian cancer. The surgeries and exams started before Pagonis could remember, at 6 months old. They had another operation when they were 3 or 4 years old, and another when they were 10.

“Since I was like 11 they would always just lift my shirt off, touch my chest and then pull my pants down and look at my vulva area,” Pagonis recalls. “And then they’d ask me questions like, ‘How are you? How are your grades?’”

Pagonis thought that because of the cancer, they would never be able to have a baby. In truth, Pagonis never had cancer. Years of intersex surgeries to make their body conform to the idea of the female sex had left them unable to feel most sexual sensation.

They spent 18 years in and out of Lurie for surgeries, hormones and exams. Doctors would ask Pagonis if they had questions. Pagonis wanted to know why they were experiencing puberty differently than other kids.

“I didn’t know I had a vaginoplasty, and I didn’t know I was intersex,” Pagonis said. “I did not know I had a castration, and I did not know I had a clitorectomy at that point. I thought I survived cancer.”

Pagonis attended college practically in the shadow of the hospital at DePaul University, watching doctors come and go as they studied for finals. It wasn’t until they learned about intersex issues at DePaul that they realized that all those visits to Lurie hadn’t been about cancer at all.

“I just thought these were my doctors that I had to go to because I had cancer when I was a kid,” Pagonis said. “And also, I was so unlucky that I had this ‘urethra problem.’”

No other major U.S. hospital has ever stated that they don’t perform intersex surgeries, so Lurie was far from the only institution performing such procedures. However, Lurie has enjoyed a sterling reputation among LGBTQ+ people since 2013, when it opened one of the first pediatric gender clinics in the nation under the leadership of Dr. Robert Garofalo, a nationally-renowned expert in transgender health. Under Garofalo’s leadership in the Gender & Sex Development Program, Lurie became the first hospital in the United States to adopt a trans-inclusive policy for its young patients.

That prestige made Lurie a prime target for a campaign to end intersex surgeries. Intersex activists have long pointed to a disconnect between the gender-affirming care for trans and non-binary youth at the hospital and surgeries done on intersex children without their knowledge or consent.

“The truth of the matter is they are very distinct and separate populations in many ways,” said Garofalo. “But there are areas where there are some overlaps.”

And those cast a pall on the gender clinic as calls to end the surgeries overwhelmed its social media channels.

The Intersex Justice Project — Pagonis and Wall’s organization of intersex activists of color — led its first protests against Lurie in 2017 and again in 2018, when the Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome-Differences of Sex Development Support Group held its conference in Chicago. About 70 people showed up to protest outside Lurie. Since that time, Lurie has been the target of a relentless campaign to end the surgeries, and protests outside the hospital have only grown.

In July, “Pose” star Indya Moore excoriated the hospital for using their image to promote LGBTQ+ inclusion. “You cannot stand W/ trans ppl & step ON intersex ppl!” Moore wrote on Twitter. The tweet set off a firestorm of bad press for the hospital as an old petition against the surgeries at Lurie racked up 45,000 signatures.

“Since I was like 11 they would always just lift my shirt off, touch my chest and then pull my pants down and look at my vulva area. And then they’d ask me questions like, ‘How are you? How are your grades?'”

Pidgeon Pagonis

Garofalo said the hospital has long been revising its polices on intersex care, but it had never apologized for the harm those surgeries had caused.

“I mean, the truth of the matter is that it has been uncomfortable for me at times,” conceded Garofalo, who does not oversee intersex care at the hospital.

On July 28, the same day the hospital announced it was suspending the surgeries, the hospital apologized.

“We empathize with intersex individuals who were harmed by the treatment that they received according to the historic standard of care and we apologize and are truly sorry,” the hospital stated in a letter signed by President and CEO Dr. Thomas Shanley. “When it comes to surgery, we are committed to reexamining our approach.”

A number of staffers within Lurie pushed for an end to the surgeries, most notably transgender research coordinator Dr. Ellie Kim, who publicly criticized the practice.

“I really owe Ellie a debt of gratitude for really stepping forward and not being shy about her thoughts on the matter,” Garofalo said. “And to that extent, I’m really proud to be where I’m at.”

Lurie’s end to intersex surgeries marks a watershed moment for intersex rights. Lurie is ranked among the top pediatric hospitals in the nation, and intersex rights activists hope that other hospitals follow suit.

But for advocates like Wall, the campaign has also taken a deep toll. Pagonis and Wall garnered support and educated the public by sharing intimate personal stories. It’s largely considered disrespectful for reporters to ask transgender people about their surgeries or genitalia. Intersex activists don’t have that luxury yet, says Hans Lindahl, director of communications for youth intersex organization InterAct.

“Something that we say a lot is that we have not yet had our Laverne Cox moment,” said Lindahl. “We’re still so under the purview of being medicalized that I think there’s a pressure that we almost have to tell these stories at this point in our movement in order to get people to listen.”

For Pagonis and Wall, that has meant revealing details about their own traumas, sexual experiences, anatomy and family histories.

And largely lost in this moment is the history of intersex surgery itself. Intersex operations were born out of gynecology, a practice developed by James Marion Sims, who performed brutal experiments on enslaved Black women without anesthesia. Although intersex surgeries were popularized in the 1960s, doctors had been doing them for years before, as Wall’s family history shows.

Wall says his family was already harassed as a Black family in the segregated South. But a Black family with three kids whose sex characteristics varied meant they were tormented endlessly.

“So for me, my intersex story comes out of this legacy that’s rooted in the South, that’s rooted in North Carolina,” Wall said. “By the time this intersex variation appeared in my family, there was knowledge and awareness of it, but people didn’t talk about it, because there was shame and stigma and secrecy.”