This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

This story was co-published with The Washington Post.

Bernice Scott estimates that she logged 30 miles, knocked on 50 doors and made 25 calls each day for “a solid two months” ahead of South Carolina’s Feb. 29 primary, campaigning for Joe Biden in a state that sent him on his road to the nomination.

She says she’s resting now, ahead of the general election push, but on Friday had already checked in by phone from her home in Hopkins, S.C., with about 10 prospective voters.

“I want you to tell me how many people you registered to vote,” she said. “We’ve got to have an agenda. I’m telling people: Write up five things you’d like to see.”

Scott wants her rural Black community to get the services and resources it deserves and expects Biden to do what he has pledged.

“That’s what I want, for him to be fair and do what’s right by the people, and help people as a whole,” she said. “I want to have access to the White House.”

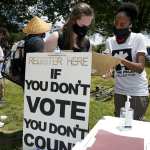

As the country is shaken by protests against racial injustice and a president whose racist remarks are contributing to his low approval ratings, Black women are not just the country’s most consistent voters — they could be among the most coveted. Headed into November, several Black women voters, organizers and activists say this could be the year they are finally valued — not just for their output, but for their input.

This election cycle is different, said Evette Dionne, author of “Lifting As We Climb: Black Women’s Battle for the Ballot Box.”

“A large part of that has to do with the literal moment we’re in, where you have a pandemic on top of this fight in the streets,” Dionne said. “Democratic politicians have long paid lip service to the idea that Black women are their base. It seems they’re taking it seriously, for once.”

Black women are only about 7 percent of the population but tend to vote at higher rates than other groups, voting at or above 60 percent in the past five presidential cycles. They are also the Democratic Party’s most loyal voters: In 2016, 94 percent of Black women voted for Democrat Hillary Clinton — the highest rate of any group, including Black men and nearly double that of White women.

They turn out at the polls, organizing their community, their church, their sorority, their families — and bring with them a sense of an American history that has often excluded them from power. Black women fought twice as hard for the vote — first with the women’s suffrage movement and then during the civil rights movement, which led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that finally gave them equal access.

Black women have long understood this country’s founding principles and set a high bar for America to live up to its ideals, said historian Martha S. Jones, author of the upcoming book, “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.”

“Black women are believers in a vision that lifts politics out of racism, out of sexism,” Jones said. “Where Black women have arrived in 2020 is a clearly discernible capacity to influence, to shape, to move and to make things happen in American politics. That is not being owed. That is taking and exercising power. There are companion forces in this moment that are propelling Black women to the fore.”

Since 2016, Black women have helped usher in the most diverse Congress in U.S. history. Their numbers grew in 2018 to 25, a record high. Black women are also serving in record numbers as mayors and have come within striking distance of becoming governor for the first time in the country’s history. In 2020, several Black women are in serious conversation for the second-highest office in the land.

Black Voters Matter co-founder LaTosha Brown, who grew up in Selma, Ala., home of “Bloody Sunday” and site of one of the major battles for voting rights in America, said that it is not just that Black women are owed — it is that America needs Black women, including as vice president.

“We have been unwavering in our fight against patriarchy and racism,” said Brown, who now lives in Atlanta. “Who else sits squarely at the intersection of racism and sexism? A Black woman is reflective of the future of America. A White male is reflective of the past and the way we’ve been doing things. Given where we are historically, politically and socially, a Black woman being in a position of power sends a particular kind of message that the country wants to move forward.”

In this moment, Black women seem to be both at the center of American politics and at the crossroads of society.

Black women were pivotal during the 2020 primary election, shifting the entire field in South Carolina, when record turnout in the first primary state with a substantial Black population propelled a languishing Joe Biden to victory, giving the former vice president the momentum to become the earliest presumptive nominee in recent history. Even with the most diverse field in Democratic presidential politics, Black women consolidated around Biden, saying they knew him and appreciated his service alongside Barack Obama.

Their choice was also a pragmatic one. Black voters, especially Black women, overwhelmingly rejected Donald Trump in 2016, and many are squarely focused on defeating him in 2020.

For many, racism is on the ballot, and their decision in the primary was based on a calculation of whom the majority of the electorate would likely be most comfortable with — and likely to support — as a general election candidate.

“Black women are sophisticated voters,” said Brown. “We’ve never had the luxury of having the person on the White horse to come save us. We’ve always had to be very practical around what our needs are, for ourselves and for our families. We vote because we recognize it’s about us and reducing harm in our community.”

Dawntoya Thomason, a stay-at-home mother of three living in Atlanta, voted in the Georgia primary and will vote in November with the main goal of ousting Trump. She said she was disappointed that the diverse field of Democratic candidates produced a White male nominee but added that the focus now must be on holding Biden accountable for his record and for how he will govern on behalf of the Black women voters he will need for victory.

“We are always the ones that get the brunt of everything, and we’re the last on the totem pole to get the things we’re voting these people into office for,” said Thomason, 38, who said her top issues include police brutality, health care, workplace discrimination and education.

“Black women lose sleep at night over injustice,” she continued. “I don’t want 2020 to come and go, where we’ve raised all this hell, and for Joe Biden to get into office and we don’t turn the heat up. I don’t want him to feel like he can rest if he becomes president.”

Amid what many voters regard as the most consequential presidential election in a generation, the focus is not just on Biden, but on whom he will choose as his running mate — and whether that will be a Black woman in particular.

Among the names often mentioned are Sen. Kamala D. Harris of California, the only Black woman who ran for president in 2020; Rep. Val Demings of Florida, whose profile rose during the impeachment hearings this year; Congressional Black Caucus Chair Karen Bass; former national security adviser Susan E. Rice; 2018 Georgia Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams; and Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, an early Biden surrogate. And Biden made a campaign pledge to pick a Black female nominee for the Supreme Court if he is elected and such an opportunity arises.

While many Black women are calling for Biden to select a Black woman as his running mate, there is also polling that shows this is not as much a priority for them as someone who will govern in their interest. But now that the election has come down to a contest between two White men, Black women say they expect a return on their investment and are looking to elect candidates who will turn their priorities into policy.

Adrianne Shropshire, executive director of BlackPAC, said she worries that symbolism could get in the way of what Black women are ultimately calling for.

“We have, in this moment, crystal clarity about what the underlying and fundamental problems are in this country,” Shropshire said. “Simply acknowledging Black women in this moment and saying there is this deep bench of Black women who could run our country is insufficient, because we’re not actually changing the things that are impeding Black women and their families and their communities from being able to live out their full potential in what is supposed to be an ever-evolving perfect union.”

Shropshire’s organization has polled Black voters and said Black women consistently point to racism, the economy and health care as their priorities, followed by education, housing, police reform and the environment. She said Black women are demanding that candidates run on addressing systemic racism.

“If you are not really grappling with and at least attempting to understand the demands that are coming from movements led by Black women, you actually dismiss the Black women who … move people to the polls,” she said.

In the dual pandemics of the coronavirus and racism, as Black women weigh how to vote safely in November, they are also focused on what’s at stake, Brown said.

“They want to see something different, they want to see change,” she said. “This ain’t going to be a regular election cycle; that ain’t where they are. We have cared for this nation consistently, and our vote is an extension of that.”