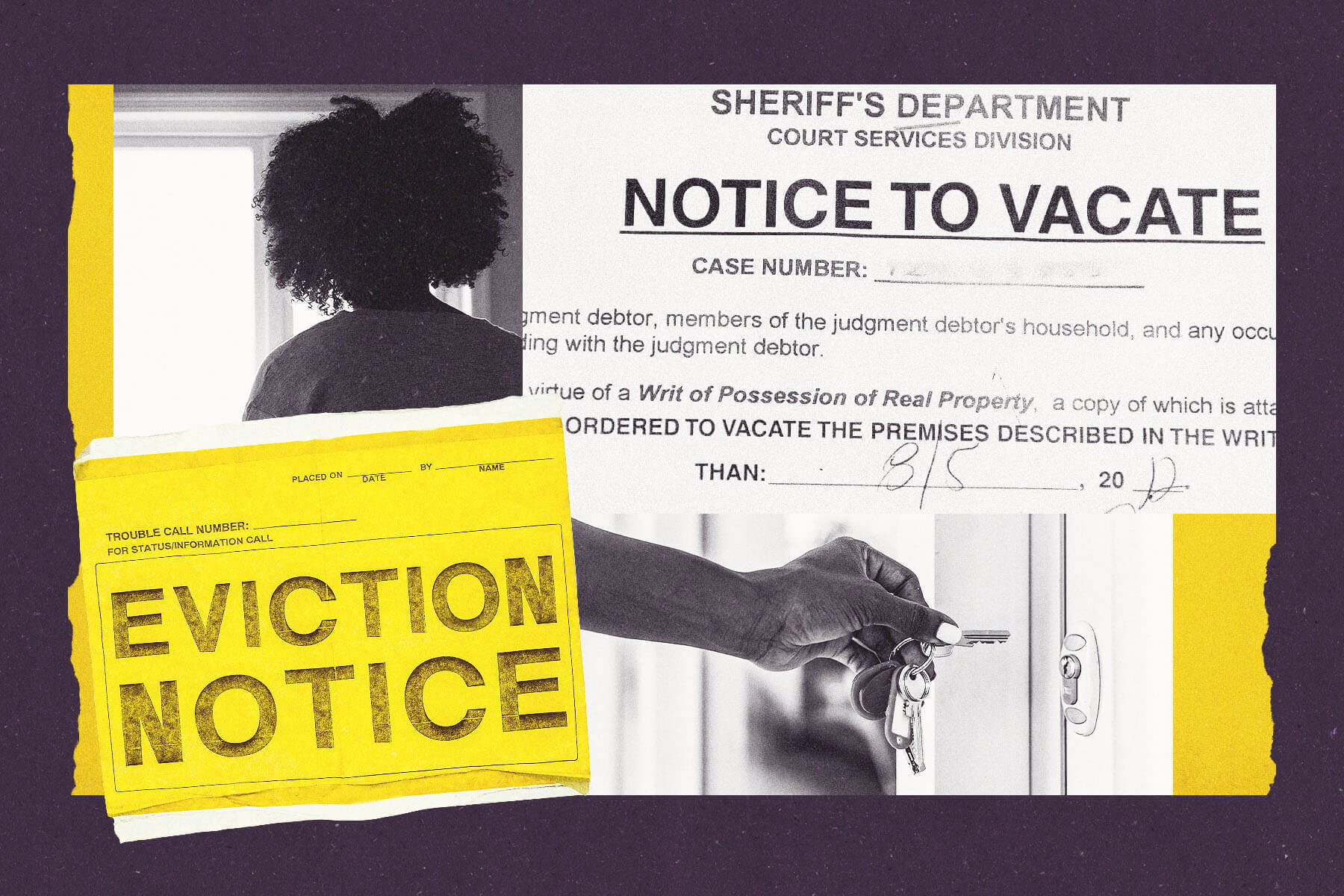

Black mothers are more likely to face eviction and housing discrimination, which has lasting impacts on their mental and physical health — as well as that of their neighbors, a new report says.

A series of studies of more than 1,400 Black women in the Detroit area also found that half of the women had experienced an eviction and that Black mothers who live in neighborhoods with increased numbers of evictions face a 68 percent higher risk of premature birth, a leading cause of infant death.

The findings come from the SECURE Study — Social Epidemiology to Combat Unjust Residential Evictions — founded in 2020 and led by Shawnita Sealy-Jefferson, an associate professor of social epidemiology at Ohio State University. Through the series of reports, Sealy-Jefferson hopes to increase the amount of research on housing inequities and how they impact the mental, physical and emotional well-being of the Black community.

“A lot of the evictions that we document that are illegal are extremely violent,” she told The 19th. “Watching other people experience that is also a source of trauma. It’s not just the people that are directly being impacted by eviction, but their neighbors.”

Over five years, Sealy-Jefferson, in partnership with a multigenerational advisory board composed of Black female activists, community members and leaders, gathered data from Black women who lived in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties. Participants completed a one hour-long survey, and the research team conducted 16 focus group interviews and 55 in-depth, one-on-one interviews with respondents who have experienced illegal, or non-court-ordered, evictions.

In 2020, the ACLU reported that from 2012 to 2016, Black women renters received eviction filings at least twice the rate of White renters across 17 states. While similar studies show that Black women are disproportionately affected by evictions, Sealy-Jefferson says little research has shown how they can affect Black women’s health.

Without a wider recognition of this systemic issue and its long-term effects, she said, the problem will continue and affect future generations.

“I will never find it acceptable that my daughter will grow up and have a higher chance of getting evicted from her home than her White colleague just because she’s a Black tenant,” Sealy-Jefferson said. “I know that if we don’t try to do something about this problem, it’s going to be our daughters’ problem.”

So far, the SECURE Study has released two reports using previously and newly collected data; one published in the Journal of Urban Health that shows the impact of evictions at the individual level, and another, published in the American Journal of Epidemiology, that analyzes the neighborhood impact of evictions.

“It’s not just the individual people who are experiencing an eviction,” Sealy-Jefferson told The 19th. Neighbors and children see them as well, compounding the impact in communities where evictions are prevalent.

Furthermore, 60 percent of participants reported high rates of adverse childhood experiences, or “potentially traumatic events” that can occur during the first 17 years of an individual’s life, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Globally, only 13 percent of people experience four or more of these events during childhood.

Twenty-five percent of the Black women surveyed over the five-year study experienced evictions as children, and were 12 to 17 percent more likely to report poor health.

Participants who experienced an eviction during childhood or those who were illegally evicted were 34 to 37 percent more likely to report worse health outcomes compared with other participants their age.

Sealy-Jefferson said eviction is not generally included in the adverse childhood experience measure.

“Why wouldn’t eviction during childhood be considered an adverse childhood experience? It’s very traumatic,” she said. “We suggest and make the recommendation that eviction during childhood needs to be one of the things that you include in the scale.”

In the next phase of the study, Sealy-Jefferson wants to engage the community to see which issues she and her colleagues should focus on next. Her report also lists action steps landlords, tenants and their neighbors should take to mitigate the issues that exist in their neighborhoods.

“I want this research to be for action,” she said. “I want to work with the community to determine what is the most pressing research they need in order to advocate for themselves and organize the next revolutions so that all humans have the right to stable, safe and affordable housing.”

Correction: This article has been updated to clarify that the findings were published in multiple reports.