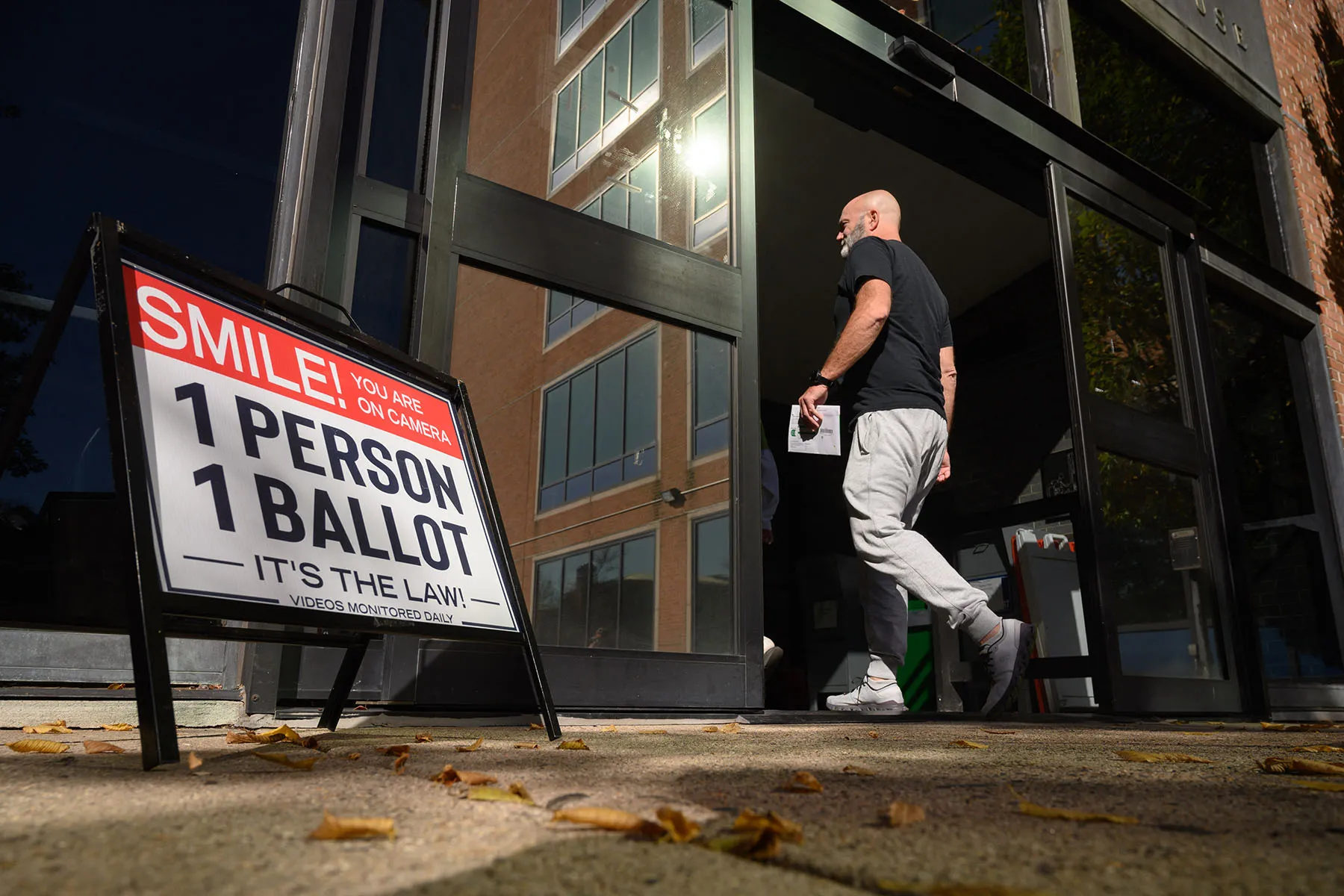

PHILADELPHIA — On a recent weekday in late October, Lisa Deeley walked around a ballot processing facility in northeast Philadelphia to show — step by meticulous step — what election workers intend to do with the hundreds of thousands of ballots that are expected to arrive at the site for the November 5 election: Receive, sort, review, extract, flatten, scan and store.

The hum of the vote processing machinery at times drowned out Deeley’s voice — and those of the other election officials — as they gave a group of journalists a tour of the facility.

“Philadelphians should just be assured of this: Voting is safe and secure, and your vote is safe and secure,” said Deeley, a Philadelphia city commissioner. “Every eligible vote that’s cast will be counted.”

Back in 2020, Deeley and her colleagues grappled with running an election amid a global pandemic, a sitting president who sowed mistrust about alleged fraud and a new vote-by-mail law that slowed down the vote-counting process in the most populous city in Pennsylvania. Four years later, Deeley is feeling more prepared.

“Everything was getting thrown at us and we could have never anticipated the level of threats, mis- and disinformation, all of that,” she told The 19th. “But now we know.”

And yet with just days to go until a historic presidential election, Deeley and her colleagues in the election workforce are grappling with a barrage of disinformation online about widespread voter fraud — of which there is no proof.

A leading figure in spreading and amplifying election disinformation is former President Donald Trump, who has claimed in recent days that fraudulent votes are being cast in Pennsylvania.

-

Read Next:

“I don’t know why Pennsylvania, amongst all the swing states, has become more of an epicenter, at least to date,” said David Becker, an election law expert and executive director of the Center for Election Innovation & Research (CEIR), during a call this week with reporters. “The only objective fact that I can look at is if memory serves, it has the most electoral voters of all the seven swing states. And so that would be a natural target.”

Voting experts say the disinformation campaign does not only seek to sow mistrust in the 2024 elections and the subsequent results. It also raises hard questions about the post-election sustainability of bad actors attacking a predominantly women-led workforce whose members have warned for years of concerns over their safety.

“The falsehoods about the election process and about people who run elections have increased and amplified and led to increased threats, harassment and intimidation,” said Carah Ong Whaley, vice president of election protection at Issue One, an organization that has advocated for more federal funding to strengthen U.S. elections. “The ways in which we are seeing states and localities have to respond — with hardened security and the kinds of protections that they need, whether it’s panic buttons or Narcan — it does feel like we’re in a heightened state.”

At the processing facility in Philadelphia, an election worker sat at a specialized desk with equipment that repeatedly sliced open envelopes with placeholder mail-in ballots placed in placeholder secret envelopes. (State law does not allow the pre-canvassing of actual ballots until 7 a.m. on Election Day). The worker then stacked the envelopes for additional retrieval at another machine.

The speed with which the pieces of equipment sprang into action is what gives Deeley confidence that 2024 will be different from 2020.

Back then, Deeley, her city commissioner colleagues and other election workers handled vote-counting during the primary and general elections in a process that took days. The national attention to the work was tense.

“We had never voted by mail before and then suddenly we had hundreds of mail-in ballots. We didn’t have any of this. We had none of this,” she said, pointing to some of the equipment.

Around the country, including in battleground states like Arizona and Michigan, election officials have opened up their ballot processing sites to help dispel the narrative that nefarious activity could happen behind closed doors this election.

But the transparency efforts, some even mandated by law, can still generate tension.

Ong Whaley with Issue One noted an incident last month in Indiana, where a longtime election official led accuracy testing on a county voting machine. Members of the public were encouraged to watch the testing and ask questions.

“She took them through the process, showing them how the process worked. As they were at the end of the process, they were off by two ballots. She knew exactly which two ballots were missing,” Ong Whaley said. “She knew the results were off, but couldn’t figure out what had happened. But as this was happening, people pulled out their iPhones and started streaming online.”

The narrative that emerged was that the machines can’t be trusted.

“It was this really harrowing experience that put her in tears,” Ong Whaley said.

Later, according to Ong Whaley, officials reviewed security camera footage that showed a member of the public had taken the two ballots.

“It clearly had been a setup and this really impacted this poor clerk. So I think there’s more stories this time around,” she said. “It’s more widespread. It’s not just in states that are key to the electoral outcome.”

Ong Whaley said she later emailed the election official to thank her for her work. The email subject, according to Ong Whaley, read, “Thank you for your service.” The worker responded by emphasizing that her staff was prepared to run a secure election.

“It’s the confidence message,” Ong Whaley said of the clerk’s response. “Which, looking at that now, is similar to things I’ve heard working with other communities. You know, don’t let the trauma define you. We’ve heard from election officials: talk about our resilience, show that we’re ready to pound sand — even though this is happening.”

Kim Wyman, a senior fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former Republican Secretary of State in Washington, has been monitoring election security issues for months. This week, some incidents sprang up: Drop boxes in Portland, Oregon, and Vancouver, Washington, were destroyed after being set on fire. Just a handful of ballots in Oregon were damaged because of a fire suppressant inside the ballot box; hundreds were damaged in Vancouver, but officials are reaching out to potentially affected voters. Authorities believe the incidents are related.

“On the downside, we’re seeing the activity we were anticipating,” Wyman said in a separate press briefing this week. “But the good news is election officials are prepared.”

Last month, a video began circulating online that purported to show someone destroying mail-in ballots in Bucks County, about 45 miles north of Philadelphia.

The video was fake, according to local election officials. Federal officials also weighed in, blaming Russian actors for manufacturing and amplifying the video. They also warned that they expected Russia “to create and release additional media content that seeks to undermine trust in the integrity of the election and divide Americans.”

Nina Jankowicz, co-founder and CEO of The American Sunlight Project, an advocacy group aimed at fighting disinformation, told reporters during the same briefing as Wyman that in 2020, some social media platforms took down election disinformation or added fact-checking or context to posts.

That has now changed. Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter, in particular, has made the popular site “a veritable firehose,” according to Jankowicz. The billionaire investor, who has endorsed Trump and has appeared with him at campaign events, is spreading disinformation and has directed people to an account deluged with rumors and conspiracy theories about the 2024 election. Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, and Google, which owns YouTube, have also rolled back some of their labeling and content moderation, a move that critics warn ultimately amplifies disinformation.

“In general, the safeguards have fallen off when it comes to disinformation at the platforms and in some cases in the research community,” Jankowicz said. “There’s a lot of folks still doing this work, but it’s become extremely risky. Trust and safety teams have been decimated, and the folks that are still there are doing really Yeoman’s work but it is like putting a bandaid on a bullet hole.”

This week, on social media and at a campaign rally, Trump pointed to the Pennsylvania counties of Lancaster and York, where election officials had announced a review of potentially fraudulent voter registration applications. Other conspiracy theories with a Pennsylvania dateline have been shared since then.

Pennsylvania Secretary of State Al Schmidt said county and state election officials have run through tabletop exercises to try to understand what sort of challenges they might face during the election, including disinformation about voter registrations

“There’s no shortage of preparation for all that,” he said.

Schmidt, a Republican who previously served as a city commissioner for Philadelphia, is not new to addressing disinformation: In 2020, he was among the officials who responded to unfounded claims by Trump at the time that 8,000 dead people had voted in Philadelphia.

Schmidt, who is now holding frequent news briefings that include addressing purported voting issues, said officials are going into Tuesday with “the benefit of having gone through 2020 to make sure that everyone is as prepared as they possibly can be.” That includes more communication with law enforcement.

“If there are any challenges, everyone knows what everybody else’s responsibilities are. And we have open lines of communication with one another.”

And in the final days of the election, litigation could play a central role.

This week, the Pennsylvania Democratic Party filed a lawsuit against the Erie County Board of Elections, alleging that election officials have failed to send mail-in ballots to between 10,000 and 20,000 voters. County officials have acknowledged the delay, and a judge ordered them to extend hours at polling sites to help voters who might need to cancel a ballot in order to receive a new one.

Trump and the Republican National Committee also filed a lawsuit this week challenging reports that election officials at some early voting sites in Bucks County were turning voters away from long lines. A judge later extended the early voting window. The Republican National Committee cheered the decision, which spotlighted an unusual form of early voting in Pennsylvania known as “on-demand voting.” The process, which can take several minutes per voter, created the long lines that were shared on social media to claim disenfranchisement.

And on Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an emergency appeal from the Republican National Committee and the state Republican Party, instead leaving in place the state Supreme Court’s order that Pennsylvania voters who make errors on the return packet to their mail-in ballots can cast a provisional ballot on Election Day that will be counted.

Witold “Vic” Walczak, legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, said the organization is monitoring ongoing litigation and the potential for more ahead of Election Day. In recent days, an effort to challenge more than 200 mail-in ballot applications in Chester County, which encompasses communities just outside Philadelphia, was denied. Other challenges have been reported. The national ACLU office and the Pennsylvania affiliate sent a letter earlier this week to local officials warning that such mass challenges violate federal and state law.

Walczak said his biggest concern about the election is if the race in Pennsylvania is so close, it’s decided within the margin of what he called improperly disqualified ballots.

“That would just be a travesty,” he said. “For an election to have integrity, it’s not just about making sure that fraudulent ballots are not counted. It also is about making sure that all eligible voters who want to cast a ballot can do so and have it counted. This should not be complicated, but unfortunately, in Pennsylvania, it has become unbelievably complicated.”

Fortunately, the actual infrastructure is not impacted by rampant disinformation, according to Jankowicz.

“The hardware is safe and secure, and the people who are out there making the nuts and bolts of democracy work, …I’m in awe of them, their commitment and their courage,” Jankowicz said.

Voters should be prepared for further spikes of election-related disinformation activity, “both online and possibly in person” according to Wyman. “But again, election officials have been planning with law enforcement to deal with these circumstances and they’re ready so let’s all just keep hoping that it goes to plan and that voters get to vote, and it’s a safe environment for everyone.”

In some cases, election officials are trying to respond to the flood of disinformation by going to the source. In Michigan, Democratic Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson has been publicly challenging Musk over the election disinformation he is posting.

“Friends: we are in the middle of a battle over the future of our democracy,” she later wrote on X. “Voting ends in less than a week. Expect bad actors to take minor issues and use them to fuel baseless conspiracy theories in order to further their own agenda. Don’t buy into their attempts to create chaos, confusion and fear.”

In Georgia, when Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger this week released a statement debunking a video that purported to show illegal voting by ineligible immigrants, he asked Musk directly “and the leadership of other social media platforms to take this down.”

“This is obviously fake and part of a disinformation effort,” he added, claiming Russian troll farms were likely behind the effort.

Jankowicz has advice for members of the public who are seeing potentially polarizing election content across their social media platforms.

“If you feel like something’s off, if you feel like something is too good to be true, if you feel yourself getting emotional, you’re probably getting manipulated,” she said. “The most engaging content, particularly right now, in this moment, is the most enraging content online, and that’s a good indication to take some space, to be a little bit more deliberate about how you consume content, to do a little bit of lateral reading. I don’t want to say fact-checking, but see how others are reporting that. See if you can source that crazy video you just saw on X or whatever. And if you can’t, it’s probably a good idea not to share it.”

Deeley in Philadelphia has a busy schedule over the next few days, attending events aimed at encouraging people to vote. Her goal is to answer questions — and to correct disinformation — about the voting process.

“The next few days are going to be grueling and exhausting because I’m trying to get everywhere,” she said with a smile. “I try to keep going because it’s important. I have a real, true, honest-to-goodness passion for this work.”

When Election Day finally does arrive, “we go into the bubble. We are here and we’ll be in here for however long we need to be.”

To check your voter registration status or to get more information about registering to vote, text 19thnews to 26797.