Your trusted source for contextualizing Election 2024 news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

For most of her life, Julianne Webber had been a very conservative voter — “just left of MAGA,” by her own estimation. Then she welcomed a second child, just as her marriage was falling apart, and became a single mother in 2019. It changed everything, including her politics.

When most of the parenting responsibilities were solely on her plate, it astounded her how just about everyone expected her to still do it all. Care for her two kids. Shuttle them to and fro. Maintain a full-time job and keep the grocery lists and do all the cleaning. Her to-do list as a parent was so long it put a CVS receipt to shame.

Day care in those early years cost her more than $125,000 total in Austin, Texas, and after that came other expenses — school and braces and extracurriculars. She rented a house in an upper-middle class neighborhood so her kids could go to a good school. But on a single income, that made paying bills — much less saving to buy a home or for her kids’ college tuition — a stretch.

“People really do just think moms are just supposed to figure it all out and their lives are supposed to go on really smoothly while they never think about what it means to raise kids,” Webber said. “I was one of those married White women who thought I was in the safe zone because we had money and I was in the church, and I thought I was this super charitable person. Now I really believe governments should help people.”

That realization caused her politics to seesaw, but she still didn’t feel quite at home in the Democratic party. Neither Republicans nor Democrats have ever done a good job of speaking to the needs of parents, and for Webber, it was glaring.

This presidential election cycle, Democratic nominee Kamala Harris has talked about offering downpayment support to first-time home buyers and creating a child tax credit for parents with newborns, all policies Webber supports, but not policies that would support her.

“I feel completely unseen,” she said.

Parents, single or otherwise, have rarely been centered in political discourse even though the issues they care about are largely economic — a perennial top concern for voters — and bipartisan. If campaigns tried to engage voters by speaking to those needs directly, they could energize a group that comprises 40 percent of households across America and spans the political spectrum.

There are signs this election cycle, when care and the cost of raising children has been discussed more than ever, could be when that starts to shift.

Parents are a critical voting bloc that we are sleeping on.”

Ailen Arreaza, executive director of ParentsTogether

“Parents are a critical voting bloc that we are sleeping on,” said Ailen Arreaza, the executive director of ParentsTogether, a national nonprofit that works to engage parents politically. When ParentsTogether surveyed voters in nine battleground states in late 2023, most ranked their identity as a parent as the most important to them, higher than their gender, race or career.

“When we think about voting blocs, we think about suburban White women, but the thing is nobody actually describes themselves as a ‘suburban White woman,’ but a lot of those women, the first thing they tell you about themselves is, ‘I’m a mom,’” Arreaza said. “The parental identity is such a powerful identity that makes such a difference in the decisions people make.”

The cost of being a parent knows no party. And when those costs balloon — as they have over the past four years for everything from child care, to summer camp, to grocery expenses — they become the prism through which many parents view their personal finances. Candidates have rarely validated that connection.

“People think about the economy and they don’t connect the dots between child care and paid leave and the child tax credit and the economy and what that means for me, for my pocket,” Arreaza said.

Take the exorbitant expense of child care: “Normal people don’t think about their daily life in political terms — similarly with child care. ‘Man, child care is so expensive’: A lot of people don’t necessarily think of it as a policy failure that needs to be addressed,” said Patrick T. Brown, a fellow at the conservative think tank the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

And so, conventionally, child care hasn’t been an issue that has been talked about much at all on a national stage or swayed votes, even though it is one of the largest expenses parents incur. The cost is so high it has led women to leave their jobs to care for their kids because those paychecks would have gone entirely to paying for child care.

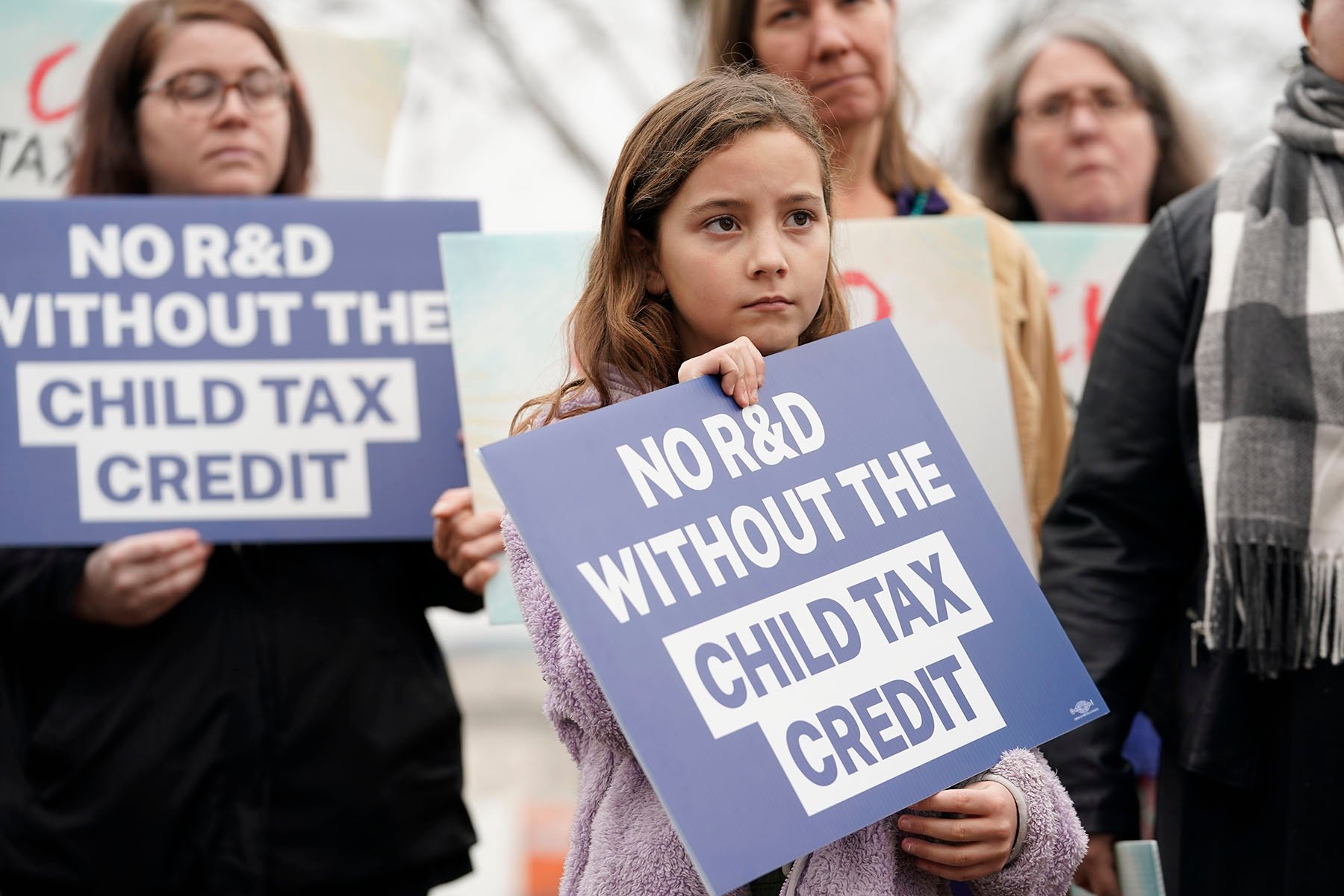

But this election cycle, family policies have more prominently shown up in both presidential campaigns. After Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, proposed a $5,000 child tax credit, up from the current $2,000 credit, Harris came out with a $6,000 child tax credit proposal in addition to upping the $2,000 credit to as much as $3,600. At an economic forum in September that focused primarily on taxes and tariffs, Trump was asked about child care. Vance’s comments on childlessness and grandparents raising kids have been some of the most talked about in the runup to November 5. And the topic came up in two debates this cycle, largely at the insistence of moms.

Reshma Saujani, the CEO and founder of Moms First, an organization that pushes for child care and other family policies, gathered signatures from more than 15,000 moms to petition for child care to be discussed in the debates. Moms First even worked to reach moms at CNN, encouraging them to email their bosses so that the child care question was included in the June debate between Trump and President Joe Biden, Saujani told The 19th. Then, given the opportunity to ask Trump one question at the economic forum, she again decided to push him on child care. By the time the vice presidential debate rolled around in October, the question was raised by the two mothers who served as moderators — CBS News’ Norah O’Donnell and Margaret Brennan — and Harris’ running mate Tim Walz and Vance spent nearly eight minutes discussing the subject.

Prior to this election cycle, child care has only ever come up in passing in presidential campaigns. In a 2004 debate, then-Sen. John Kerry mentioned he’d like to “raise the child care credit by $1,000 for families to help them be able to take care of their kids.” In 2008, then-Sen. John McCain called Head Start, the federally funded child care program for very low-income families, a system “that cries out for accountability and transparency and adequate funding.” In 2012, then-President Barack Obama said child care and the child tax credit “are not just women’s issues,” but economic ones.

By 2016, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and Trump both touched on the topic briefly, with Trump adding that “as far as child care is concerned and so many other things, I think Hillary and I agree on that. We probably disagree a little bit as to numbers and amounts and what we’re going to do.” And all of that leads to the moment earlier this month, when during the vice presidential debate, Vance conceded that “we’re going to have to spend more money” to improve child care, a statement that marks a definitive break with where Republicans have historically been on the subject and shows that the parties have finally started to converge on tackling it.

They are recognizing that you have to talk to moms and you have to talk about child care as an economic issue.”

Reshma Saujani, CEO and founder of Moms First

“They are recognizing that you have to talk to moms and you have to talk about child care as an economic issue,” said Saujani, who called the success of Moms First’s campaign on child care the greatest professional accomplishment of her career. “Something has shifted. I think now the thing will be this: Regardless of the outcome, do we finish the fight?”

There is still a long way to go on how candidates talk about child care. Trump’s rambling non-answer to the child care question at the economic forum barely included “concepts of a plan” he offered for other topics. And Walz framed his answer to the paid leave and child care question during the vice presidential debate almost entirely as a business issue, failing to mention that his state has been one of the few to implement expansive paid leave and child care policies.

Neither Republicans nor Democrats have figured out how to run on these policies, experts said — in most cases, they’re barely even crawling.

Republicans, who have generally positioned themselves as the family party, have done well on the messaging but are short on substance, Brown said. And Democrats have been heavy-handed on the policies — often to the tune of millions and billions — that stand little chance of passing in any divided Congress. Biden failed to pass a $400 billion-plus child care, paid leave and child tax credit package through a split Congress in 2022.

What is remarkable, Brown said, is how much both presidential campaigns this cycle agree on many of these subjects where they haven’t before. “I don’t think Sen. Vance and I are that far apart,” Walz said during the vice presidential debate. It suggests there is room there to pass policies that many Americans support. Polls consistently show that Republican and Democratic voters are largely in agreement that they’d like to see more federal investment in child care, paid leave and the child tax credit.

In state and local races, there’s a similar shift to addressing parents as a voting bloc as more parents, especially moms, are running for elected office — and winning — than ever before. The Vote Mama Foundation, which does research on representation of moms in politics, has found that many of those candidates are building their campaigns around issues affecting parents. This year in Texas, Republican House candidate Hillary Hickland is running as a mom of four who is an “advocate for her children and families.” In Arizona, Democratic House candidate Stephanie Simacek describes herself as “a teacher, a mother” working to build “stronger families and brighter futures for Arizona.”

That’s why in Austin, Webber has put more of her focus on organizing events for local candidates she believes could have a more direct impact on her life.

“Part of what I’m trying to do in my own life and involvement is to try to get people to talk about this. I’m trying to be the loud single parent in the room everywhere I go these days,” she said.

In the presidential race, she’ll be casting her vote for Harris this year — not because of her policies on the economy or parents, but other things like climate and reproductive rights.

There was a moment when she thought Harris might sway her as a parent voter. During a September economic speech in Pittsburgh, Harris said, “I want Americans and families to be able to not just get by but be able to get ahead.” It brought tears to Webber’s eyes, because it spoke to her deepest desire as a parent — to thrive.

But what Webber still didn’t hear was “the ‘how’ for me and my situation in her policies,” she said. “I feel about 50 steps behind. I am struggling to figure everything out for my kids and I could use help but I don’t know where to find that. I don’t know if I think it’s going to change fast enough for me and that feels lonely.”

The path to treating parents as a voting bloc begins with legislators who are parents themselves.

Allie Phillips knows that. When she introduces herself to voters as she knocks on doors in Montgomery County, Tennessee, she often leads with her identity as a mom. Before she was running for a seat in the state House representing her home of Clarksville, she was an in-home child care provider and once a single parent. She talks about that, too. And she talks about her abortion, about having to leave Tennessee, where abortions are illegal, for a medically-necessary procedure in 2023 after she learned halfway through her pregnancy that her fetus would be unable to live outside the womb. It was a baby she loved and wanted, who already had a name: Miley Rose.

“My experience as a single mom … growing up in a family that didn’t have a lot of money, I have firsthand experience of these struggles, because I live them, and I still live through them,” said Phillips, who is running as a Democrat in a Republican stronghold. “When I talk to other moms, we discuss the cost of raising kids — from child care to basic needs — and it’s a challenge that I’m consistently hearing from people, especially here in Clarksville.”

The top complaint from many parents in her area is finding reliable and affordable child care, and Phillips knows how those struggles can cascade across a community. Many of the parents whose children she cared for struggled to pay when they had to miss work because their child was sick, and most day cares require those payments even when a child misses in order to keep their spot. If parents can’t pay, they lose their child care and their ability to work.

“My race offers a voice for working moms who feel like they’ve been overlooked, because we have,” Phillips said. “I feel like this year more and more women, especially moms, are paying attention to politics.”

Representation of moms in state legislatures has increased nearly 50 percent in just two years, according to the Vote Mama Foundation. Six years ago, almost no state allowed candidates to use campaign funds to pay for child care — now 36 do. Still, only 8 percent of all state legislators this year are mothers with minor children, and few candidates are yet tapping into using funds on care.

Tennessee ranks nearly at the bottom in terms of representation, with only two moms of young children in the state Senate. There are none in the House. If elected, Phillips would be the only one.

When moms have a seat at the table, we bring a perspective that is often missing — and desperately missing.”

Allie Phillips, candidate for TN State House 75

“When moms have a seat at the table, we bring a perspective that is often missing — and desperately missing. Right now in Tennessee, that perspective isn’t even in the House at all,” Phillips said.

She supports universal pre-K for 4-year-olds in Tennessee, a bill that failed to pass in the state earlier this year, as well as expanded state support to lower the cost of child care and a mandatory state paid parental and medical leave policy.

Over the past several years, it’s been that desire for parents’ needs to be recognized in legislation that has fueled a surge in mothers running for elected office, from school board and city council seats all the way up to Congress. Candidates who have lived the struggles parents face can make the needed connection missing from political discourse, about how those issues are matters of economic policy, said Sarah Hague, Vote Mama’s chief program officer.

“When you have a working class person — especially a mom — running for office, that translation is natural because their lived experience is informing their policy platforms,” Hague said. “So often these issues are seen as women’s issues — paid family leave, maternal health care, child care — and they’re fundamentally economic issues. It’s a shared concern that unites parents across the political spectrum. This will be a crucial issue driving voter sentiment in the upcoming election.”

Living on a military base in Alaska, Samantha Deddo has seen how so many of the challenges parents face cut across party lines. They’re the kinds of things people of any background can agree on. The kinds of things that can push people to vote.

Deddo grew up in a conservative family in South Florida before relocating to Alaska with her husband, who is an active-duty service member. These days, she leans more Democrat, but still votes split ticket, just as enthusiastically casting her vote for both Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski and Democratic Rep. Mary Peltola.

Alaskans have issues they care about that affect them uniquely, particularly around the environment and the oil industry, but they also face one of the most severe child care shortages in the nation.

“I think Alaskans are the one demographic that really have more things that bring them together than pull them apart … and I think being a parent almost makes everyone feel a little more human, because you can relate to late nights, the growing pains,” said Deddo, who lives in Anchorage and works for an e-commerce company. “When you are a working mother and you’re talking to other working mothers, definitely the cost of child care — I think it can be something that can actually unify people.”

Deddo wasn’t able to get her daughter into a child care center until she was a year old, even though she’d been on a waiting list from the time the baby was 10 weeks old. Another military spouse who had previous child care experience agreed to care for her daughter until a spot opened up, for $2,400 a month.

This election, child care is one of the top issues she’s thinking about going to the polls, along with maternity and paternity leave, the cost of living and housing and the child tax credit. That’s what she votes on, Deddo said. She’ll be casting her ballot for Harris.

Deddo believes the pandemic woke many up to the struggles of parenting — whether they had a child or not.

“People are making enough noise around child care and being a parent and what we need, and I don’t think that’s going to go away,” Deddo said. “They are going to have to start doing something.”

Arreaza, too, believes the time that has passed since the last election cycle has helped parents see what is possible if they advocate for their needs. The child tax credit was temporarily increased to its highest level ever, delivering monthly checks to parents and cutting the child poverty rate in half before Congress failed to make that expansion permanent and the child poverty rate rose back up. A separate bill passed in 2021 included the largest-ever, one-time allotment for child care — $39 billion — which helped stave off mass day care closures and increased mothers’ labor force participation rate by 2 to 3 percentage points, according to a study by the White House Council of Economic Advisors.

The world that I dream of is a world in which parents recognize that this is what we deserve.”

Ailen Arreaza, executive director of ParentsTogether

Parents now know that passing those kinds of policies is possible, Arreaza said.

“There’s so much shame that exists with parenting, and when we talk to parents about this at ParentsTogether we often hear them say things like, ‘Well I had kids, I know it’s my decision to have kids so now it’s my problem to solve,’” she said. “The world that I dream of is a world in which parents recognize that this is what we deserve.”

And if they demand it, candidates will have to start listening. “In 2028,” she said, “can this just be the status quo?”