This column first appeared in The Amendment, a biweekly newsletter by Errin Haines, The 19th’s editor-at-large. Subscribe today to get early access to future Election 2024 analysis.

Patricia Dean of Tucson, Arizona, has been canvassing for Vice President Kamala Harris all month, knocking on doors throughout her community. She’s also planning to talk to her brother and a friend to try to persuade them to vote for Harris.

“I don’t want to sit at home after the election and say, “I sure do wish I had done something to help her get elected,” said Dean, 59. “I feel like I’m doing everything in my little way to get the word out.”

Virginia Lamp has voted for former President Donald Trump twice and plans to do the same again this fall. She said she’s worried that “the Democrats might pull something” and concerned about political violence after a second assassination attempt against Trump in Florida last weekend.

The 60-year-old Republican has been praying about the outcome of the election and talking to neighbors in Savannah, Georgia, through her church, at her local food bank, at the convenience store, about the issues on their minds and the importance of voting.

“I’m not telling people how to vote, but telling them to vote and talking to them about the state of the country,” Lamp said. “People have to make up their minds for themselves. Otherwise, they’ll come back and blame you if it doesn’t go their way, and that’s going to cause even more violence than what we have now.”

Barbara Bennett, 70, said her husband, son, daughter and son-in-law are all on the same page and plan to vote for Harris. But she’s already dreading Thanksgiving, after confirming her suspicions that her sister is likely supporting Trump — or at the least, may not vote at all this year.

“She’s not saying it, but she’s got an excuse for everything Trump does or says,” Bennett said. “I tried to say, ‘hey, this is not about a policy, this is about democracy. This is a binary choice here.’ She just isn’t listening.”

After their phone conversations descended into shouting matches, the sisters mainly text now. But about a week ago, Bennett said she decided she was done trying to change her sister’s mind about the election.

“I gave up. She’s my closest living relative, so it was worth a try.”

With 47 days to go, we have officially entered the dark phase of the presidential campaign.

In the past two months, Trump has survived two assassination attempts — and has blamed Harris and President Joe Biden for the increasingly violent political climate. As the Democratic presidential candidate, Harris has been the subject of racist and misogynist attacks, online and from her opponent and other Republican surrogates.

And Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, is currently tripling down on his demonization of a community of Haitian migrants legally living and working in Springfield, Ohio, spreading a racist hoax he knows to be false in what he claims is an effort to raise concerns about illegal migration. But neither man is burdened by facts: Trump continues to tell the lie that the 2020 election was stolen and that the 2024 election could be rigged.

Dean, Lamp and Bennett were among the respondents to the latest 19th News/SurveyMonkey poll who said that they were engaging in democracy by talking to friends and family about the election — something 7 in 10 registered voters said they were doing. According to the poll, 90 percent of registered voters say they’re planning on voting in November.

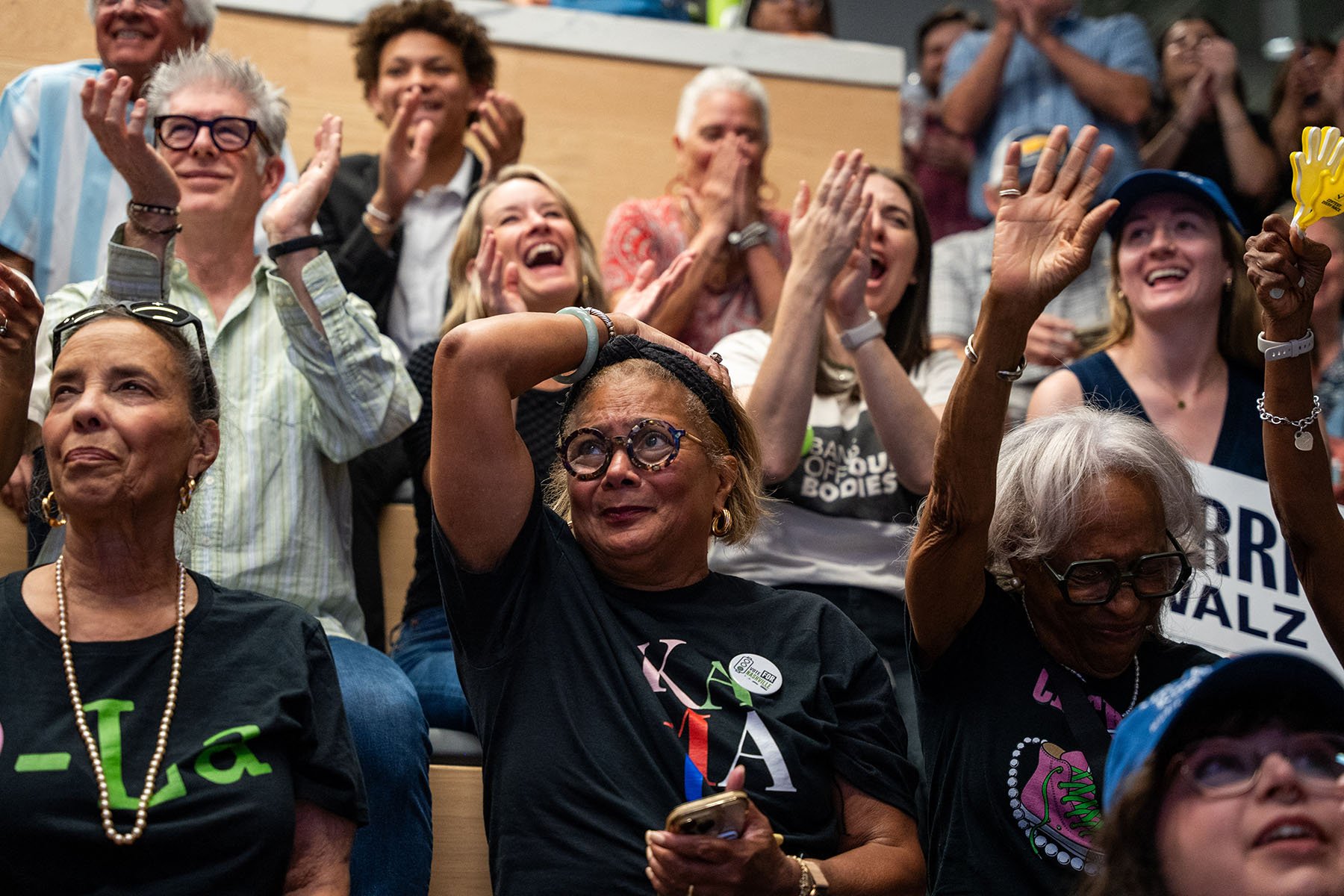

Many Americans, regardless of political ideology, came into the 2024 election worried about the future of democracy and feeling like the stakes are existential for them or someone in their lives. Amid the atmosphere of joy that has marked Harris’ candidacy and the excitement among Trump supporters for their candidate’s potential return to the White House, there is also fear — of the unknown, the uncertain and the unprecedented in our politics. We have been here before, and if the past is prologue, we can expect worse in the coming weeks.

Former First Lady Michelle Obama warned us about this exactly a month ago. In her speech at the Democratic National Convention, she said: “Now, unfortunately, we know what comes next. We know folks are going to do everything they can to distort her truth. … Let us not forget what we are up against.”

In communities across the country, Americans are doing something — what Michelle Obama urged people to do in the face of lies, dread and what can feel like the uphill battle of the home stretch of what will likely again be a close election. For some, it’s a way beyond voting to help them process their concerns; for others, it’s a thing they’re doing despite their feelings, because the election feels that consequential.

After the debate between Harris and Trump, Dean said she felt joyful and energized, but she described this week as “a little rough” after seeing big Trump banners back in her neighborhood. For her, they’re literally signs of “the ugly stuff” she saw in 2016 and 2020.

“I know it’ll just be a matter of time before the men in the big trucks with the flags will be driving around on the weekends,” Dean said. “It was ugly then and it’s going to be ugly now. But I have faith … I believed that Biden was going to win and he won. I believed Trump was going to win in 2016 and he did. I’m hoping I’m right again and Harris is going to come through. It’s really important that we don’t put such a dangerous man back into the White House.”

The majority of registered voters agree that the outcome of the 2024 election will determine the future of democracy in America — 67 percent strongly agree and 21 percent somewhat agree, according to our poll with SurveyMonkey. Partisans are more likely than Independents to think so, and Democrats (76 percent) even more likely to strongly agree than Republicans (65 percent). Registered voters who are 65 years old or older — who favor Harris in this election — are also more likely than younger voters to say the election could determine the future of democracy.

Harris is making the case for freedom, a distinction from Biden’s pitch that the election was about the threat to democracy posed by Trump. But she has also criticized Trump’s divisive approach and rhetoric — vowing to be a dictator, but only for a day, and telling evangelical supporters that they won’t have to vote again in future elections — as dangerous.

“When you have that kind of microphone in front of you, you really ought to understand at a very deep level how much your words have meaning,” Harris told a panel of Black journalists in Philadelphia earlier this week when asked about his comments on Springfield.

“When you are bestowed with a microphone that is that big, there is a profound responsibility that comes with that, that is an extension of what should not be lost in this moment, this concept of the public trust … You cannot be entrusted with standing behind the seal of the president of the United States of America engaging in that hateful rhetoric that, as usual, is designed to divide us as a country, is designed to have people pointing fingers at each other.”

There is still time for the politics of division to play out in this election. They are predictable, particularly for a candidate who has been running for president for the better part of a decade. We know him and what he is willing to do to win — he has told us and shown us repeatedly. What the country’s response will be could determine not just an election, but whether and how we move forward as a nation.