In early May, as the National Audubon Society hosted its 21st annual Women in Conservation event at a swanky restaurant in Manhattan, CEO Elizabeth Gray handed out awards named after writer and conservationist Rachel Carson to recognize the next generation of women environmental leaders and activists.

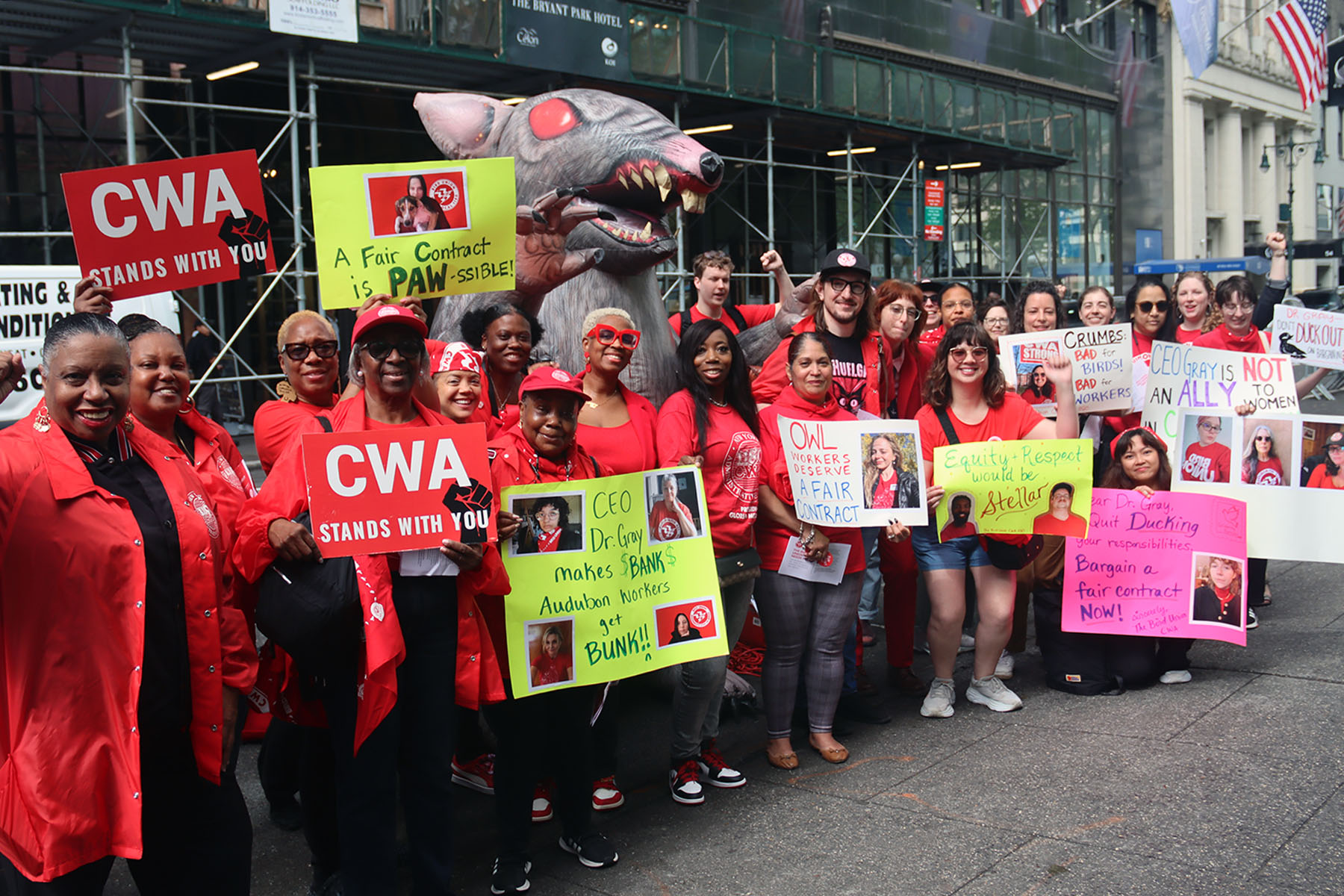

But outside the event, a couple dozen of Audubon’s women staffers had gathered for a protest related to their own environmental careers. Equipped with megaphones and wearing red union t-shirts, they held up hand-drawn signs that said things like, “CEO Gray is not an ally to women in conservation (ask her about parental leave).” Others opted for bird puns: “Owl workers deserve a fair contract.”

Their union — called the Bird Union-CWA, part of the Communications Workers of America — has been in contract negotiations with Audubon for over two years. Workers voted to unionize in September 2021 following a series of disastrous events. In 2020, during the early days of the pandemic, the national conservation organization laid off over 100 workers. Later that year, an investigation by Politico described a toxic workplace culture for women and people of color and the resignation of two diversity, equity and inclusion staff members.

Soon after, an internal audit — launched by the society’s board in response to the Politico reporting and conducted by the law firm Morgan Lewis — found evidence supporting the magazine’s allegation that Audubon had “a culture of retaliation, fear and antagonism toward women and people of color.” Witnesses told the auditors that women had gotten negative performance reviews or were passed over for raises after asking for more resources. Women also pointed out significant pay disparities between themselves and men, the audit concluded.

Now, nearly three years later, union members say pay disparities remain and that union members are being left out of new benefits offered to non-union staffers like expanded paid parental leave. Meanwhile, the contract negotiations drag on.

“We are really asking for the very basic things that would allow us to survive at this organization and hopefully one day thrive,” said Sarah Friedman, a digital advertising and engagement manager with Audubon who is on the union’s organizing committee. “We want to reach a fair contract and make Audubon a better place to work and fix these problems like pay inequity.”

The union’s membership fluctuates seasonally between 252 and 260 full-time employees and accounts for a little less than a third of all staff at the Audubon Society. It primarily represents people who have jobs in conservation and science work and roles in development, finance, IT, HR and marketing. It does not include managers or executives.

In May, the union released a report about pay inequities at Audubon based on wage data provided by the organization. The analysis found that among union members, women systemically made less than men, with women of color earning the least. In a job category that includes development, finance and marketing, for example, White men made almost 13 percent more than White women and 16 percent more than women of color. The difference in pay is similar in the job category that includes employees who do conservation and science work.

Christopher Thomas, a staff representative with CWA Local 1180, which represents the Bird Union, said that in the bargaining process, the union has sought to create pay equity across gender and race and bring transparency to how compensation works at the organization. The union is advocating for an annual 4 percent increase across the board, he said. The union is also asking for 12 weeks of paid parental leave.

“We support across-the-board increases, and we do so because there is a mountain of historic evidence that describes that merit-based pay increases are very susceptible to bias, corruption and favoritism,” said Thomas. “We have met management half way and have included that a portion of increase be tied to merit in a number of different proposals.”

Maxine Griffin Somerville, Audubon’s chief people and culture officer, said in a statement that the union’s report is incomplete because it did not account for the salaries of non-union employees. “It also does not account for important factors that impact compensation nor does it represent the compensation proposals that are being negotiated between Audubon and the Union right now,” she said.

Thomas said the union would welcome the data to do a pay analysis for all workers at Audubon, but needs the organization to provide it. In the meantime, union members say that discretionary raises, which are based on performance reviews and come with no guaranteed annual cost of living adjustments, lead to pay disparities over time.

Krysten Zummo, who was hired as a grassland ecologist at Audubon a year ago, said that she and a male colleague who were hired for the same job were both asked to complete self-evaluations and rank themselves on a tier that would determine their raises. Zummo ranked herself in the middle tier because she had only worked at the organization for a few months and felt that she hadn’t yet proven her worth. She later learned that the coworker, who had started a month later, gave himself the highest ranking.

At Audubon, Zummo said, these lower rankings directly influence what raise they are eligible for. “This is kind of how it all starts with the pay gap, the gender disparity especially,” she said. She believes a better system is one where raises are given equally to all as cost-of-living increases rather than based on merit.

A spokesperson for Audubon declined to comment on the existing pay raise system or provide details on efforts that have or are being made to address pay inequity, citing ongoing bargaining with the union.

In an emailed statement, Somerville wrote that the organization has made significant investments in compensation for all staff, including updating the way decisions are made so that they are “based fully on the job requirements and blind to individual candidates.”

The union is also fighting to increase paid parental leave. In 2021, that was just two weeks. Last year, Audubon enhanced its benefits package for non-union employees, who now receive six weeks of parental leave. But it didn’t change it for union members.

In October, the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint, finding that the Audubon Society had “bargained in bad faith or violated the rights of their union employees” in four different cases brought by the union. National labor law bars discriminating against employees as a way to encourage or discourage union membership – and rolling out benefits to Audubon employees that weren’t offered to union members violated that law, the board concluded.

The limited paid parental leave time affects union members who are thinking of starting families, said Friedman, who has worked at the organization for 10 years and been involved in the union since the start.

“I turn 34 in a couple of weeks. My husband and I aren’t sure if we want to have kids, but a major reason we are putting off the decision is because I work at Audubon,” she said. “I could never imagine having a child while working here under these policies.”

In her statement to The 19th, Sommerville pointed to a new strategic plan adopted last year to implement equity, diversity, inclusion and belonging at the nonprofit. The organization also announced a commitment of $25 million to the work; she declined to provide details.

She also said that Audubon has made changes in the executive leadership team, with women now making up a greater proportion of leadership than in the past.

“Our entire leadership team is wholly committed to this work so that Audubon is a best-in-class workplace where all staff thrive regardless of gender, race, age or ability,” she wrote.

The Bird Union’s effort is part of a broader trend in environmental organizations, with Greenpeace USA forming a union in 2020 and Defenders of Wildlife following in 2021. Reflected in that shift is a desire to see gender equity in a field that, like so many others, was historically led by White men. More women now lead these nongovernmental organizations, according to Green 2.0’s transparency report card, which analyzes employee data from environmental groups.

During an interview late last month, Thomas, the staff rep for the Bird Union, said that in recent weeks, the organization has shown signs of being more receptive to requests put forward by the union. Because of that, he’s hopeful both sides will be able to reach a deal soon.

“I think they want there to be a contract at Audubon and everyone to be able to focus on the work at Audubon,” he said. “It is also a signal for the other environmental organizations that it is really in everyone’s best interest to get to a deal and have everyone focus on the mission.”