It was 1781 when a 14-year-old girl made her debut as an opera soloist in Saint-Domingue, the former French colony now called Haiti. She was a free person of color, the first person of African descent to star as the soloist in a French opera, and soon became the main woman opera singer in Port-au-Prince. Yet, for the first four years of her career, she was only ever referred to as the “young person” in newspaper announcements.

It wasn’t until her ailing employer wrote in his will that she be paid her back wages that her name — Minette — first appeared in a written document. For more than two decades, the prima donna was publicly known by first name only. Shortly before her death, however, an advertisement in New Orleans displayed her full name: Minette Ferrand.

Ferrand, a star in her time, left the scantest of paper trails; other Black women musicians left even less, according to Givonna Joseph, a 67-year-old Black opera singer based in New Orleans. Joseph, who also teaches at Loyola College of Music in New Orleans, said it’s especially hard to find women’s contributions in historical documents because of the way their names were typically listed in recital programs or concert flyers. Oftentimes, they would read “Mademoiselle” with a first name only or a first initial and last name — as was custom in polite Creole society then.

“That leaves you with little to no information about these women, not adequate enough to find who they were and what they were actually doing,” Joseph said.

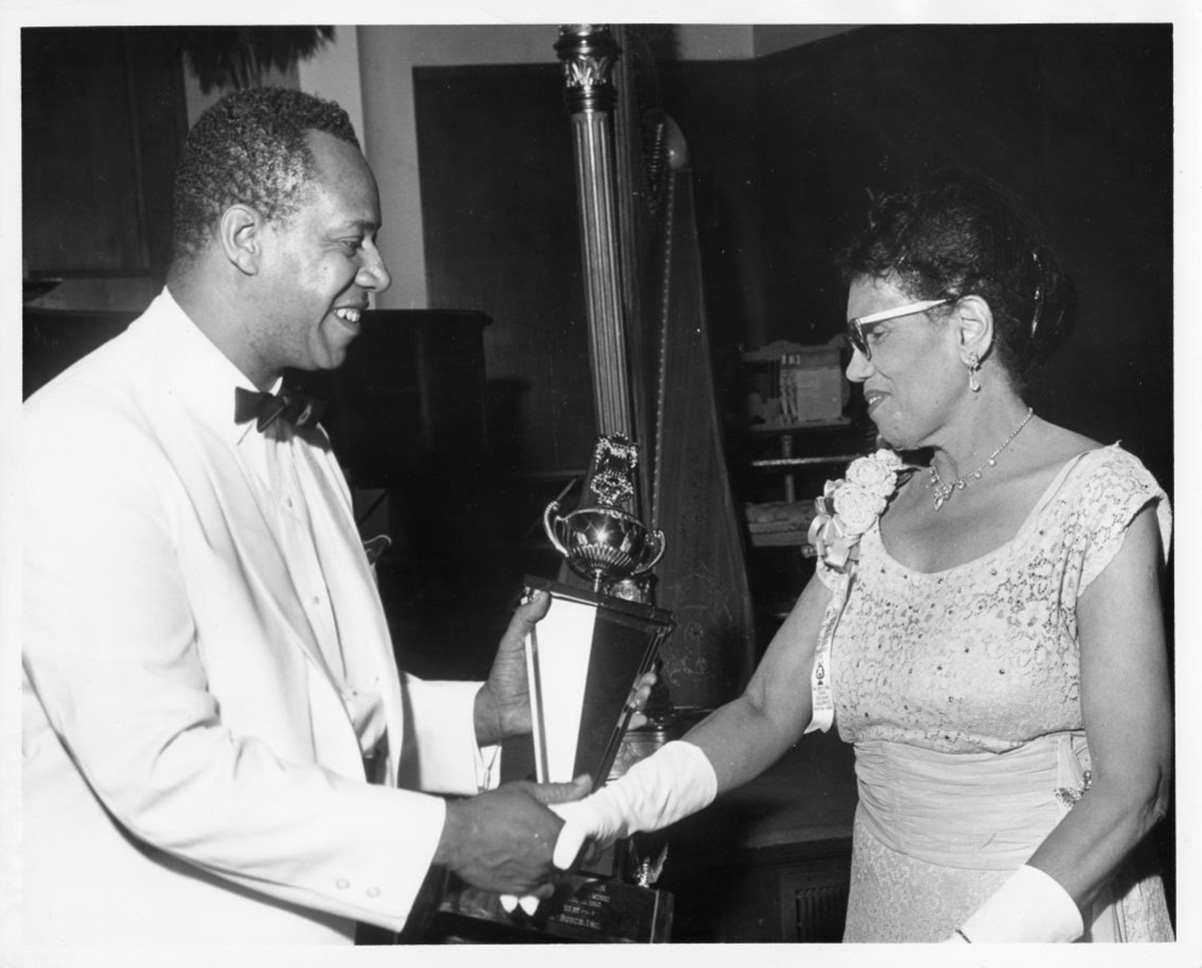

She and her daughter, also an opera singer, founded OperaCréole in 2011 to unearth and highlight the hundreds of years of hidden or lost musical contributions of Black classical musicians and composers. They join a modern movement to preserve, recognize and perform some of these forgotten works — a growing list of repertoire that includes operas, symphonies and choral compositions.

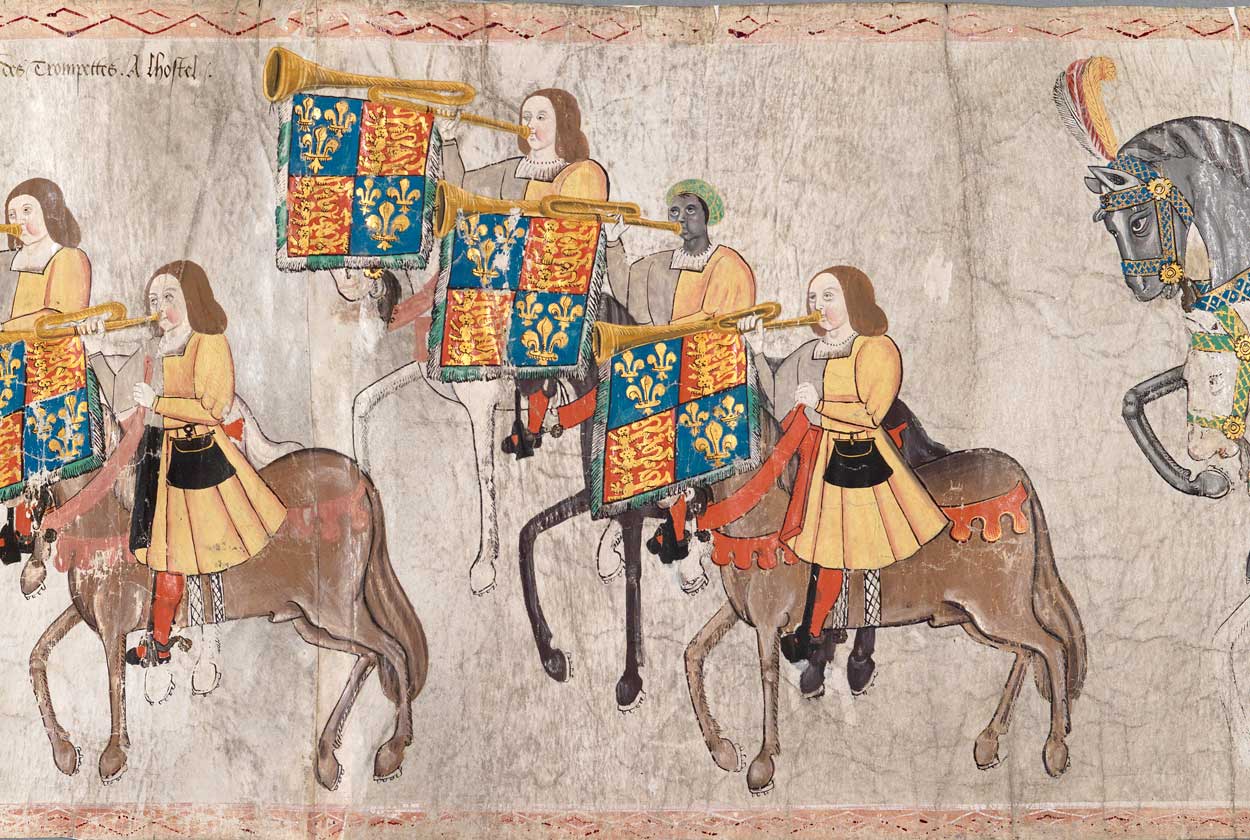

Joseph’s history class covers 500 years of musicians and composers of African descent, starting with John Blanke, who was Black and the royal trumpeter in the courts of King Henry VII and Henry VIII. Surviving paintings of him, dated to the early 1500s, show that he had dark skin; they are the only evidence of a Black person in court during the Tudor era. Joseph said she wants her students to learn about the past to inspire them to think of what’s possible for their futures.

“Not everybody’s a history buff,” Joseph said. “But I try to tell these stories in a way that I hope will let someone know a little bit more about who they are and who they can be. Too often in our history, women are told you can’t do this or you shouldn’t do that.”

Joseph said people are always amazed when they meet her, asking: “Wait, you’re a Black opera singer?”

“Opera has never been White,” Joseph said. “It’s been sold that way, and those composers were smashed down in historical records. It’s never been just a thing for White Europeans. When I talk to young people about these composers who were doing extraordinary work in the middle of slavery, in the middle of having every excuse you could possibly have not to excel, I play their songs, say their names and tell their stories.”

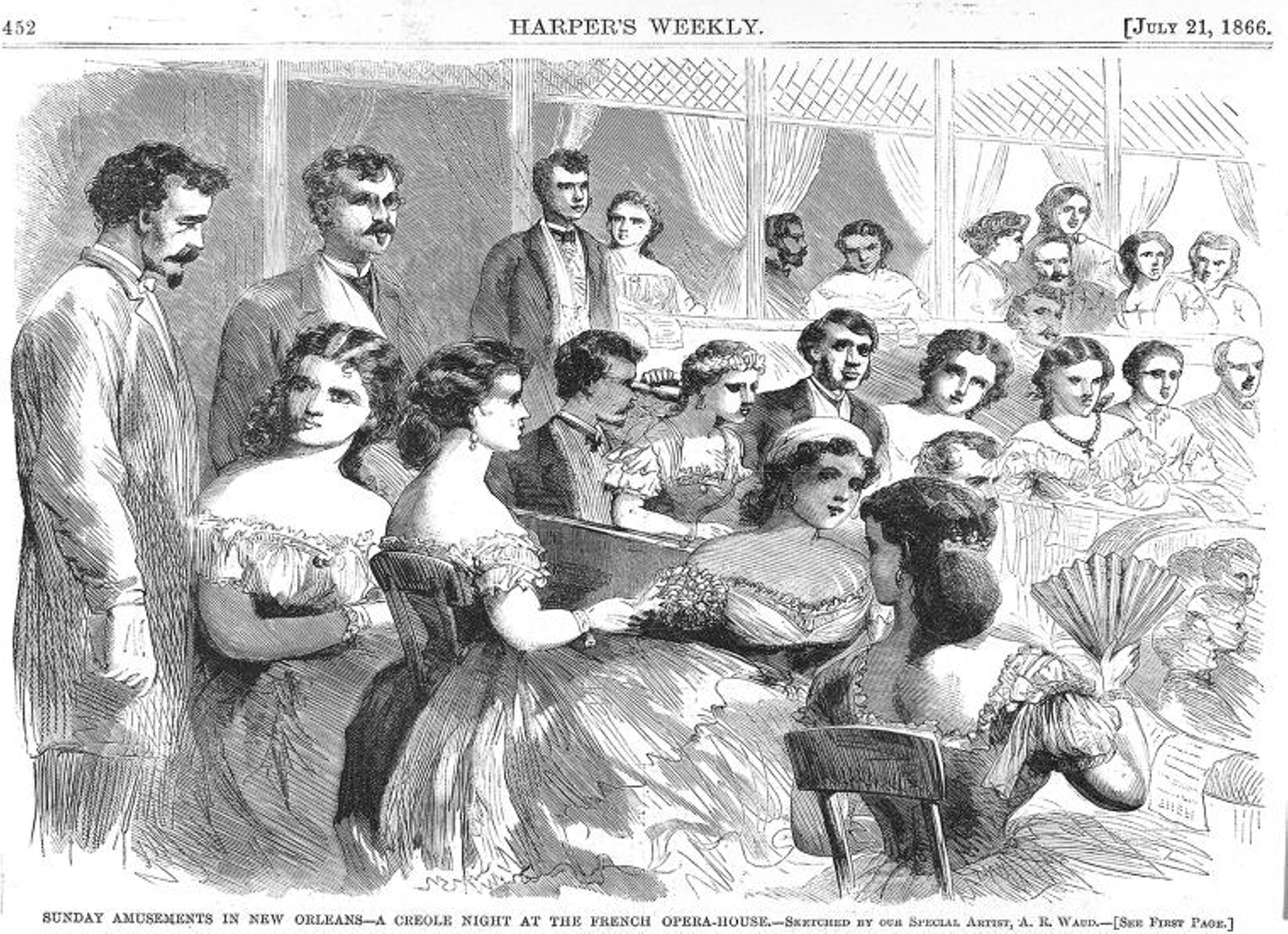

In the late 18th century, New Orleans was the first city in the United States to have a full opera season. Between 1796 and 1919, the city — which came to be known as the “Opera Capital of North America” — had five opera houses, often with multiple operating at the same time. Works by predominantly White European men had their American premieres at the French Opera House in New Orleans.

However, Joseph said there was also a significant interracial network of classical musicians and composers in the city — including and extending beyond opera — whose work largely remains hidden from public memory. To explain how this happened, Joseph pointed to racial tensions and violence during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War and then Jim Crow laws that mandated racial segregation in the South. As a result, Black people’s works were often put in drawers, filed away or in some cases burned.

Joseph said that it seemed like around the world, somebody kept making a decision to silence certain people’s story.

“It’s unfortunate that there has been — over our history as a culture, as a country, as a world — someone that has felt that in order to be on the top, they have to push everybody else down,” Joseph said. “You shouldn’t have to bury somebody else’s story in order for your story to excel, and we’re still learning that today. It’s especially frustrating for me with an opera company run by two Black women – it’s harder to find the works written by our own gender.”

Some stories persist, though many classical works have been lost — including operas, symphonies and other compositions.

The only Black woman composer known to be active in New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century was Sister Marie Seraphine. She moved to Louisiana from Puerto Rico and joined the Colored Sisters of the Holy Family when she was 17. Her superiors quickly recognized her musical talent. She was enrolled in a Catholic music school, open to only White students at the time, and learned to play the piano, organ, strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion. Widely known as the “Convent Maestro,” the nun went on to direct the orchestra at St. Mary’s Academy, taught music to orphans and established a boy’s band before passing away in 1932.

About 30 years after her death, Sister Marie Seraphine’s convent relocated, and all of her compositions were lost except one.

Around the same time, in 1926, Camille Nickerson, an Afro-Creole woman, began teaching at the School of Music at Howard University in Washington D.C. While earning her master’s degree, Nickerson spent a year collecting, transcribing and creating arrangements of Afro-Creole folk songs.

Her compositions ultimately moved Creole folk songs into the classical lexicon, which is how much Indigenous music spread around the world and influenced other classical works, Joseph said.

Most of Nickerson’s unpublished arrangements for voice, piano and choir — some of which were popular in the mid-20th century — have been lost, have gone out of print or are difficult to track down.

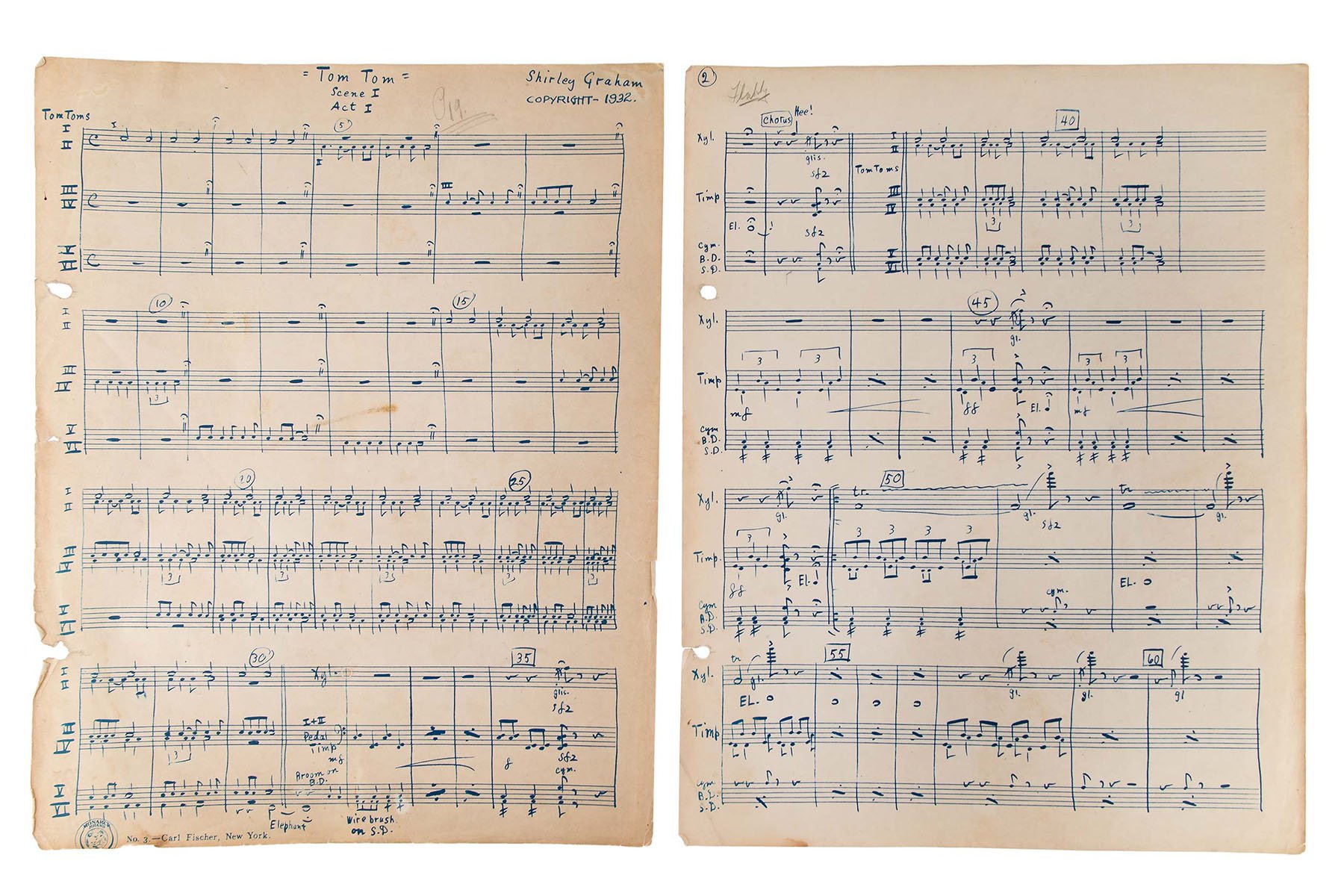

But Black women never stopped composing. The first Black woman to write and produce an opera with an all-Black cast was Shirley Graham Du Bois, the second wife to W.E.B. Du Bois. The three-act, 16-scene opera was called “Tom-Toms: An Epic of Music and The Negro,” featured an all-Black cast and orchestra and opened at Cleveland Stadium in 1932.

“I’m the happiest girl of my race,” Du Bois wrote in a 1932 article published by The Black Dispatch newspaper. She went on to say that it was her childhood dream to see “an opera by a Negro and with an all-Negro cast, telling the story of Africans and tracing their life and music.”

Ten thousand people came on opening night. The next performance drew 15,000. However, the opera’s two-day premiere was also its swan song; it closed after its second show. There were hopes that the show might continue to Madison Square Garden, but it never happened due to the state of the stock market, which continued to hit record lows during the Great Depression. Despite its popularity, it slowly faded from public memory as Du Bois’ interests shifted to more political leanings. The opera seemed to disappear until a score was found among Du Bois’ papers in 2018 by a Yale doctoral student studying American and African American studies.

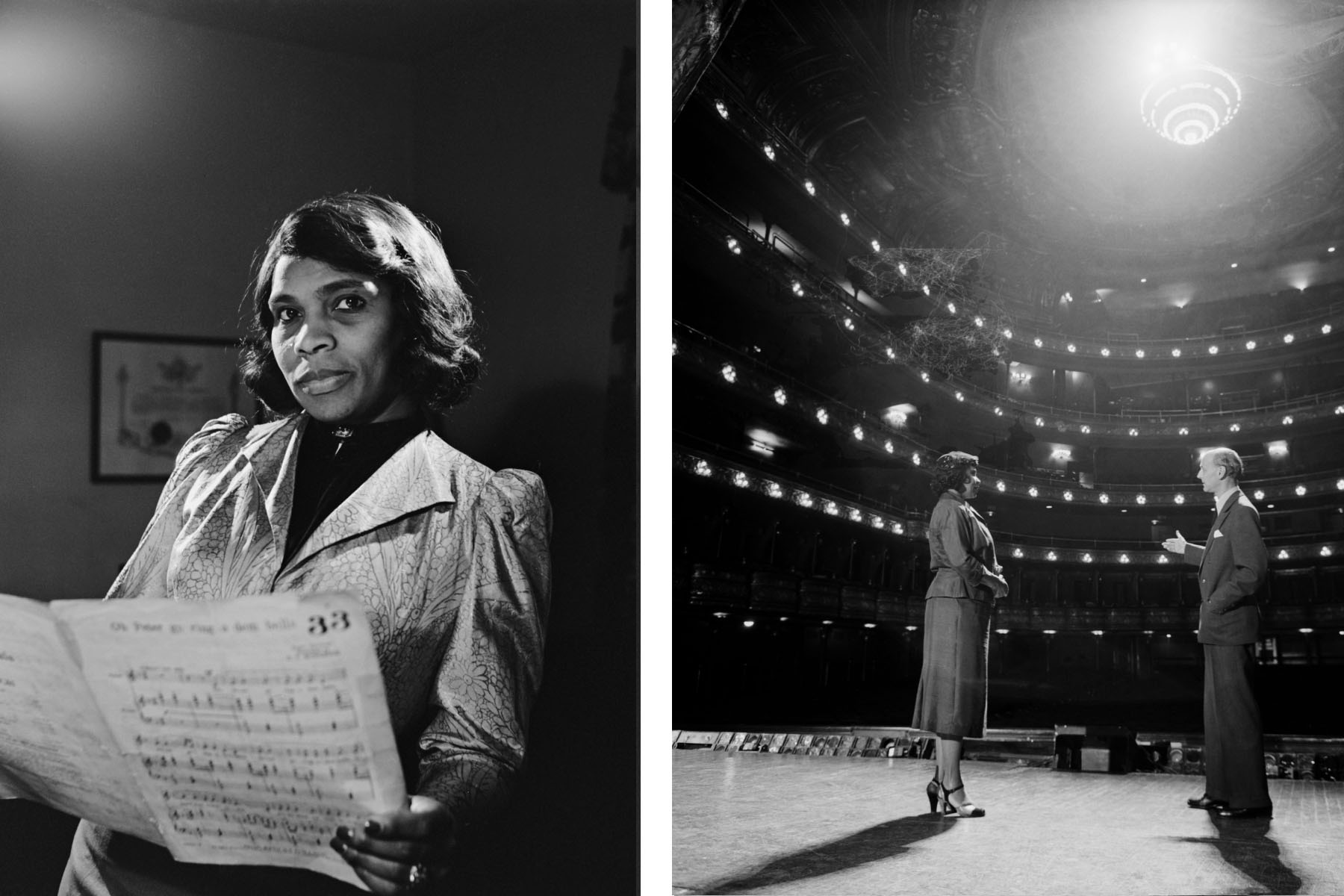

Also in 1932, Marian Anderson, considered one of the finest American contraltos of her time, made her debut in London. She continued to successfully tour throughout Europe for the next few years, even appearing before the monarchs of Sweden, Norway, Denmark and England. However, Anderson remained less known in her own country, where many concert venues were closed to her due to segregation. Most famously, the Daughters of the American Revolution denied her the right to sing at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., in 1939 — a move that caused an outraged First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to resign from the organization. Instead, with backing from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the secretary of the interior, Anderson performed a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The performance drew 75,000 people.

Sixteen years later, Anderson became the first Black singer to perform as a member of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

Joseph said it’s important to highlight Black women’s contributions to a genre that is often misrepresented and misunderstood.

“Opera is portrayed as this very hoity-toity, uppity thing — that you have to have three degrees to understand,” Joseph said. “But it’s messy. Think of soap operas: They decided at one point when television was a new thing that they wanted to have stories to get women attached to, so they could sell them soap powder. All of those stories are just like opera stories. It’s people making bad decisions set to beautiful music.”

Joseph said only allowing certain stories to make it to the stage has a significant impact on what stories are told in the future.

“We have all these ideas about the way women are talked about in history, which limits who girls grow up to think that they are, the full expanse of who they are,” Joseph said. “And there’s this idea that because you’re Black, you’re supposed to fit in a certain box, but the box was made by somebody else.”