WAUKEGAN, Ill. — On a November afternoon inside Robert Abbott Middle School, six eighth grade girls quickly filed into a small but colorful classroom and seated themselves in a circle.

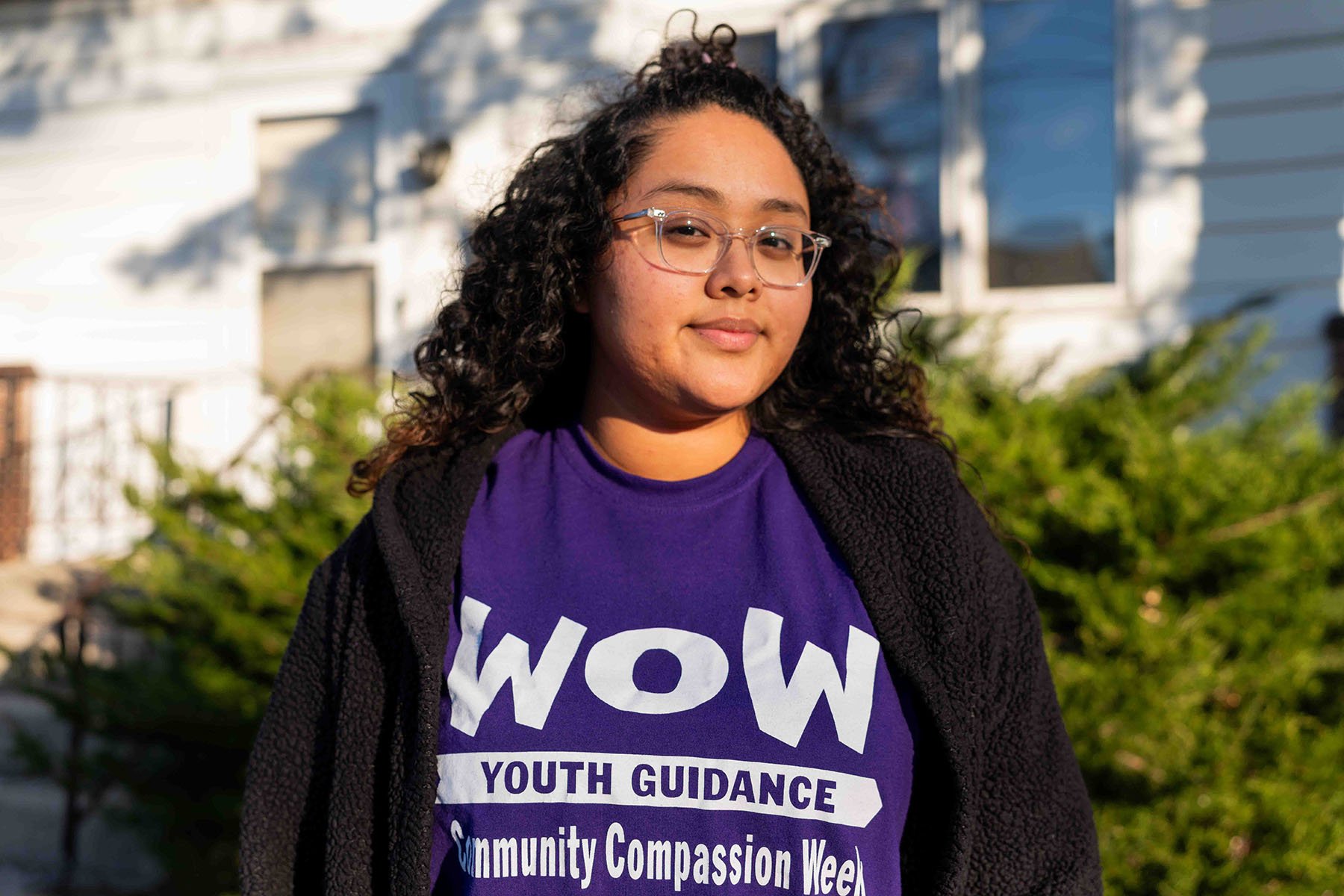

Yuli Paez-Naranjo, a Working on Womanhood counselor, sported a purple WOW T-shirt as she led the group in a discussion about how values can inform decisions.

“Do you ever feel like two little angels are sitting on each of your shoulders, one whispering good things to you, the other whispering bad things?” Paez-Naranjo asked the girls. The students nodded and giggled.

At the 50-minute WOW circle, girls have a chance to set aside the pressures of the school day, laugh with and listen to one another, and work through personal problems. The weekly meeting is the centerpiece of individual and group therapy that WOW offers throughout the school year to Black and Latina girls, and to students of all races who identify as female or nonbinary, in grades 6 to 12.

Created in 2011 by Black and Latinx social workers at the nonprofit organization Youth Guidance, WOW’s goal is to build a healthy sense of self-awareness, confidence and resilience in a population that is often underserved by mental health programs. Youth Guidance offers WOW to about 350 students in Waukegan Community Unit School District 60, which serves an industrial town of about 88,000 located about 30 miles north of Chicago. Just over 93 percent of the district’s 13,600 students are Black or Latinx, and about 67 percent are classified as low income.

The program also serves public school students in Chicago, Boston, Kansas City and Dallas. WOW counselors work with school-based behavioral health teams, administrators and teachers to identify students with high stress levels who might benefit from the program.

Recent research shows that WOW works: At a time when teen girls’ mental health is in crisis, a 2023 University of Chicago Education Lab randomized control trial found that WOW reduced PTSD symptoms among Chicago Public Schools participants by 22 percent and decreased their anxiety and depression.

Multiple hurdles, including funding, counselor burnout and distrust of mental health programs stand in the way of getting WOW to more students. But one way the program overcomes impediments is by bringing the program to the place students spend most of their time — school.

Paez-Naranjo, who is so well-liked among Abbott students that even kids who aren’t in the program seek her out, posed a question to the group.

“Let’s talk about positive and negative consequences of certain decisions. How about fighting?” she asked.

“The only positive outcome is you may find out how strong you are,” said Deanna Palacio, one of the girls.

“Why fight when you can talk it out?” asked another student, Ka’Neya Lehn.

“Right? What’s the point?” said a third girl, Ana Ortiz.

A baseline study of over 2,000 girls in Chicago’s public schools, conducted by the University of Chicago Education Lab team, found “staggeringly high” rates of trauma exposure: Nearly one third of the participating young women had witnessed someone being violently assaulted or killed, and almost half lost someone close to them through violent or sudden death. Some 38 percent of girls in this group showed signs of PTSD, double the rate of service members returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Paez-Naranjo and fellow WOW counselor Te’Ericka Kimbrough, who works at Waukegan Alternative/Optional Educational Center, have supported students who have suffered sexual assault. Some participants in their circles are teen parents. Others are trying to resist negative peer pressure. Still others are in families that are struggling financially.

Compared to other students, Black and Latinx students have a harder time getting mental health support in school. In-school mental health support targeted to girls, especially evidence-based, sustained programs like WOW, is scarce or nonexistent in many public schools.

Even scarcer is mental health support from providers who can give culturally responsive care. Only 5 percent of U.S. mental health providers are Latinx. Just 4 percent are Black. WOW intentionally links students with counselors who share their race and ethnicity.

Sally Nuamah, associate professor of urban politics in human development and social policy at Northwestern University, said the tendency of adults to view Black youth as more adult-like than their White peers can shroud the mental health needs of Black children. In addition, the girls’ own positive behavior can mask their needs: In a study of the WOW program, participants were found to have strong school attendance and at least a B average, even as more than a third showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

“They are perceived as resilient and possessing grit,” Nuamah said. “This obscures the real mental health needs of students of color and perpetuates institutionally racist policies because these students are not perceived as needing the same resources.”

Nacole Milbrook, Youth Guidance chief program officer, said WOW was developed to address often overlooked needs among Latina and Black girls. “Girls have been left out [of mental health support initiatives], mainly because they are not making trouble,” she said.

The nonprofit is working to figure out just what parts of the program work best. End-of-school-year participant surveys, which use measures similar to those used in the Education Lab study, suggest that the relationships developed between WOW counselors and participants are a key reason the program is effective.

“Our theory of change is that WOW works because … [students] are attending this incredibly powerful support group every week and this support person is there every day in the school for them,” said Laurel Crown, Youth Guidance’s senior research and evaluation manager.

WOW counselors are “systemically engaged” in the schools where they are based, said Fabiola Rosiles-Duran, WOW program supervisor for Waukegan. They stay informed about whole-school dynamics by being part of behavioral health team and all-staff meetings.

Counselors Kimbrough and Paez-Naranjo added that daily access to teachers and staff provides wraparound support for their students. The counselors’ presence also helps them respond to acute situations immediately and follow up on student progress each school day.

“If I need extra support with a student, I can lean on the school behavioral health team,” Kimbrough said. She added that if she has a student in crisis, being able to see that student regularly helps her know if their interventions are working.

Providing intensive support to students every school day can be emotionally taxing for WOW counselors. Youth Guidance provides group training and individual support to help counselors maintain their own emotional health.

During their first year on the job, counselors participate in three hours of curriculum training each month plus three days of refresher courses. Many training activities mirror those the counselors will later use with their students.

WOW leaders also check in every weekday to offer support to the counselors. Those new to WOW also attend a two-day, three-night retreat that “helps counselors and staff figure out what’s happening within ourselves,” said Ngozi Harris, Youth Guidance director of program and staff development, “so we have the fuel to do this work.”

One study found that the multiple layers of support WOW offers students and staff, at a cost of about $2,300 per participant, are cost-effective. Still, that can amount to a significant portion of a district’s or school’s annual budget.

But Jason Nault, Waukegan CUSD 60’s associate superintendent of equity, innovation and accountability, said WOW is well worth the cost. Earlier this year, the district’s Board of Education approved a two-year extension of its contract with WOW and its counterpart for male students, Becoming a Man, at a cost of $4.2 million.

Nault said data Youth Guidance collects at the end of each school year shows WOW students are less depressed and anxious, more self-confident and have less post-traumatic stress.

“WOW provides our students with a safe place to work through some of the issues they face,” Nault said, and also gives them real-life skills and strategies they can apply to challenging situations.

Yet multiple implementation challenges exist for WOW and other school-based student support programs.

The work of counselors is isolating and can lead to psychological burnout, said Inger Burnett-Zeigler, associate professor of psychology at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

“There is significant and chronic and traumatic stress the WOW counselors experience,” she said. The WOW counselors themselves meet regularly for training and circles to build their own emotional health, and Burnett-Zeigler is working with WOW to develop and test an evidence-based mindfulness intervention for counselors.

“Counselor well-being is important in and of itself,” said Burnett-Zeigler. It also can support youth outcomes, she said.

Another barrier experienced by programs like WOW is that, according to research, Latinx and Black families are more reluctant to seek out mental health support and treatment than other ethnic and racial groups. The WOW program works to build trust not only with the students, but with their parents and family members.

“Families of color have a tendency to not name mental health issues as mental health issues,” said Milbrook, the chief program officer for the organization that oversees WOW. “Seeking treatment still has a stigma, even for children.”

Milbrook said the school-based setting is key for destigmatizing both mental health conditions and treatment.

“Being in school and participating in the groups with other students, understanding that you’re not the only person dealing with these same problems, and talking about them in ways that don’t feel like their idea of traditional therapy” all help, she said.

Also essential, Milbrook added, is fostering a sense of belonging. “We give the participants WOW T-shirts, and now they can walk around the school identifying as Working on Womanhood girls,” she said. “All of a sudden, nobody is ashamed to be in this group.”

Deanna, the Abbott eighth grader, added that the sense of belonging WOW fosters has helped her feel less lonely.

“You feel heard and understood here,” she said.

Although the school setting presents advantages for WOW, it can also involve implementation challenges. Youth Guidance’s Harris said that both WOW staff and school staff want positive outcomes for WOW students, but WOW’s healing-centered approach might conflict with a school’s discipline policy. So, school staff might initially be wary of program staff and counselors.

Schools also sometimes underestimate the expertise of the counselors, and sometimes even ask them to take on tasks like cafeteria monitoring that are not their responsibility.

“It takes a year of building relationships, really being intentional about how to collaborate with the school,” Harris said. “Until that trust is built, you are an outsider.”

Paying for the program is another challenge. Although Waukegan CUSD 60 covers all program costs, most districts do not. Youth Guidance relies primarily on philanthropic support to pay for its programs.

Youth Guidance is less likely to tap into public funding sources like Medicaid because the public assistance program’s cumbersome processes can lead to higher program costs and even threaten the trust WOW builds with students and their families.

For example, WOW counselors often make numerous phone calls to parents, or visit them at home. It’s time well spent, Milbrook said, but it’s not financially productive. Counselors can only bill their time to Medicaid after a parent signs a consent form.

Despite some of these implementation challenges, WOW leaders and counselors consider the Waukegan WOW program a success.

“As a whole [group], I’ve seen a decrease in anger and fights,” said Paez-Naranjo, the Abbott Middle School WOW counselor.

The lessons on mindfulness during WOW circles at Abbott have helped Ana Ortiz build confidence in her emerging identity as a young woman. She, like her other classmates in the program, returned for a second year after starting WOW as seventh graders.

“Before I came here, I was not finding myself at all,” Ana said. “I wanted to know, how is it, being a woman? I wanted to know what other girls’ opinions and perspectives were.”

Paez-Naranjo said she has seen Ana’s growth since last school year.

“Ana has stepped out of her comfort zone a lot more. She feels more confident to share intimate details about her life and is willing to support anyone in need,” said Paez-Naranjo.

“And she is so much more smiley,” Paez-Naranjo added. “You can see her smile from a mile away.”

Later, on her way out of the Wednesday Abbott WOW circle, Ana turned back to offer a final take on how WOW has helped her.

“It makes me feel free in here,” she said, flashing one of those smiles. “I understand better about myself.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Recommended for you

From the Collection