Your trusted source for contextualizing the news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

Kathryn Edin had just published a book on America’s poorest people when she was asked if she’d be interested in turning her research lens on poor places. When she did, Edin — a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University — was surprised at what she found.

She had long studied poverty in urban areas, but the poorest places in this country were actually rural, with long histories of power imbalances, corruption and an eroding social infrastructure that has kept poor people poor for generations. Many people think of rural America as predominantly White, but the poorest places in the nation are rural communities of color — and women are often the most disadvantaged.

“It was almost like a conversion experience,” Edin said. “Social science has been realizing slowly that where you grew up is as important for your life chances as your genes, your behavior, the quality of health care you receive. Place is hugely determinative — it determines to a large extent how things turned out for us. And I think as an individualistic culture, we really strain to believe that.”

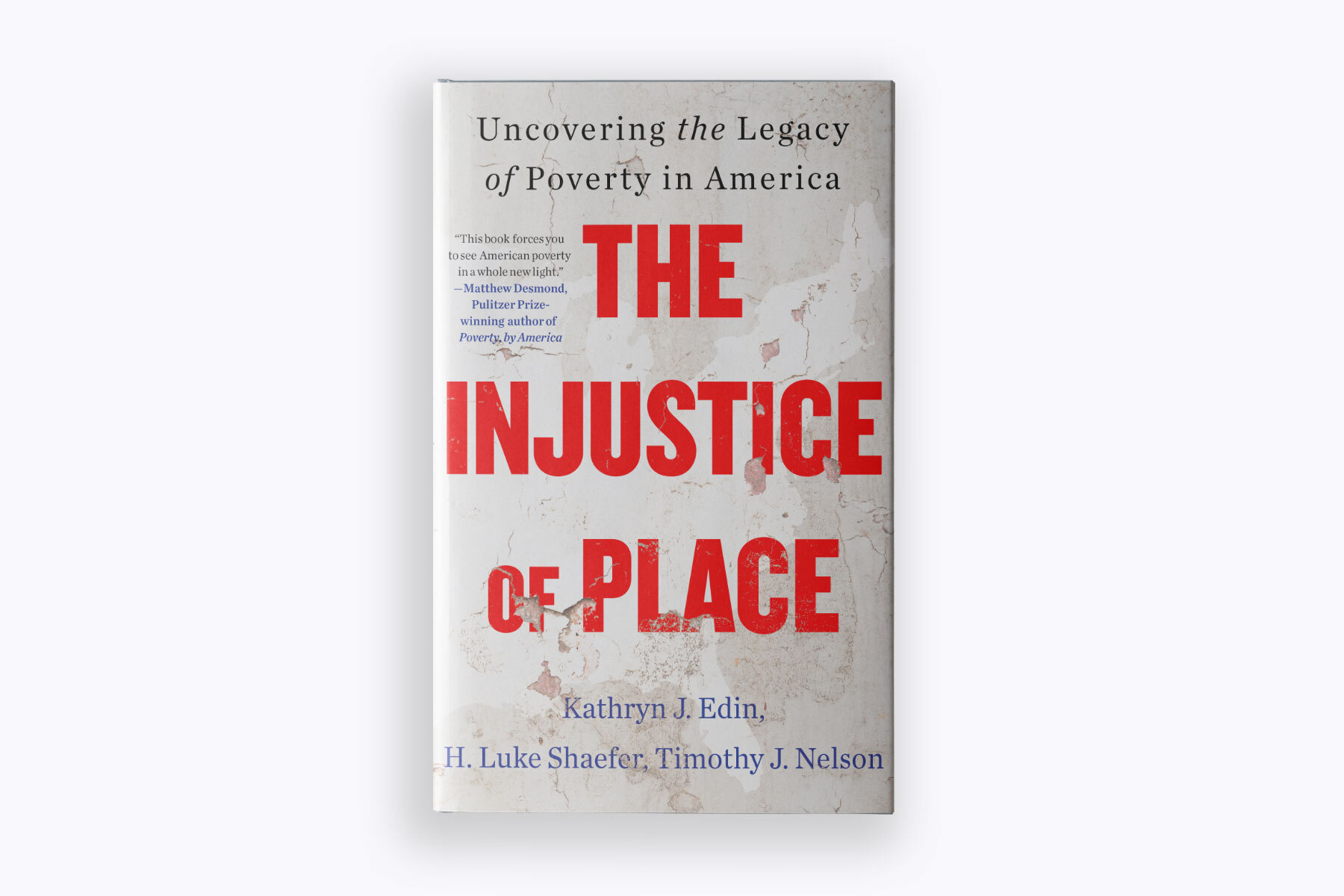

In their new book, “The Injustice of Place,” released on August 8, the authors — Edin; Luke Shaefer, professor of public policy at the University of Michigan; and Timothy Nelson, a sociology lecturer at Princeton University — found that the poorest places in the United States fall into three primarily rural regions: Latinx-majority South Texas, Appalachia and the vast Cotton Belt of the American South.

The researchers created a new measure of poverty in U.S. communities called the Index of Deep Disadvantage, a holistic view of people’s lives that takes into account cyclical, cumulative and structural measures of poverty. They found that those in disadvantaged areas face unequal schooling, structural racism embedded in government programs, the collapse of infrastructure and entrenched public corruption — and can generally expect to die a decade earlier than Americans in more advantaged places.

The 19th talked to the book’s authors about how they identified the poorest places, what those places had in common, how poverty is perpetuated across generations and potential policy solutions.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Mariel Padilla: What factors did you consider when identifying the poorest places, and why?

Kathryn Edin: We started with cyclical measures that go up and down with the business cycle, such as income-based measures and the poverty line. Then we chose two health measures, called cumulative measures because the experience of being disadvantaged gets under your skin and prior experiences wear on your body. We chose one at the beginning of life, low birth weight, and one at the end, life expectancy. And then we wanted a structural measure of poverty because some places just have more opportunity than others. So we used the measure of intergenerational mobility: If a kid is born poor, what are that child’s chances of making it to the middle class?

Luke Shaefer: The amount of data that we have on communities — from CDC life expectancy data to social mobility rankings taken from IRS tax records — is much greater than it’s ever been before, so we have information down to the county level and for the 500 largest cities. We put all of it into a machine learning analysis tool to rank every county, and then traveled to about 75 percent of the poorest 200 places.

-

Read Next:

Where are the most disadvantaged places in the United States, and what do these locations have in common?

Edin: It really was stunning when we put all of these indicators together and then put all the rankings on a map. That was when we knew we had a story because these places were not random. They were not cities for the most part; they were these kind of forgotten rural regions, almost all in the 14 Southern states.

Shaefer: The book really tries to link the stories of these places together: You have Eastern Kentucky, which is predominantly White in the Cotton Belt; the Tobacco Belt, which are predominantly Black; and then South Texas, predominantly those of Mexican-American descent. What really struck us is that each place had its own unique facets, but in many ways the stories were linked.

Edin: As we began digging into the histories of these places and embedded our graduate students to live in these places, we soon realized that everything was the world capital of something. Greenwood, Mississippi, was the cotton capital of the world; Crystal City, Texas, was the spinach capital of the world; Manchester, Kentucky., had been the salt capital of the northeastern United States before becoming a major coal mining region; and Marion County, South Carolina, had been the tobacco capital of that region. What we realized is that all of these places had been grounded in a small group of White elite who established a single industry and then began exploiting, either through slavery or other practices, huge numbers of poorly paid, barely surviving laborers to create vast wealth.

-

Read Next:

What were you most surprised by?

Shaefer: This work was just endless surprises for me. First, I think like a lot of Americans I didn’t really understand rural America. I thought these areas were predominantly White, but when you get into the most disadvantaged areas, many of them are predominantly Black American, Mexican American and Native nations. I also didn’t expect to write about many of the themes we ended up highlighting in the book, from violence to the opioid epidemic. Working with Kathy has made me realize that we often don’t even know the right questions to ask until we go out and talk to people and get embedded in communities.

Timothy Nelson: The importance of place and the legacy of history is much stronger than people think, and that’s the biggest thing we took away from this. We tend to think in individualistic terms in our society, but the role of context in these places is the most important lesson that we’d like to share with readers.

What perpetuates poverty?

Edin: We began to refer to these disadvantaged places of sprawling inequities between “the haves” and “the have nots” as internal colonies. After these dominant industries had their heydays in the 1920s, they were brought down in the 1960s by automation and foreign competition.

By doing our ethnography embedding in these communities, we were able to identify a variety of mechanisms that led to the perpetuation of disadvantage: One was a highly separate and grossly unequal system of education that started when children were valued as laborers first before they were students. Second, there’s been a collapse of social infrastructure, such as movie theaters, roller rinks and bowling alleys. These institutions really catch people when they fall and build social bonds within a community. Third, there’s violence that we found was rooted in a lack of opportunity and low social mobility. Then there’s the problem of corruption from those original elite families whose descendents continued to skim and exploit every resource that remained in ways detrimental to ordinary citizens. And finally, there’s systemic racism in government policy that we really saw in Marion County, South Carolina, for example, in the face of repeated flooding after multiple hurricanes. White citizens were actually better off than Black citizens because of government policy.

Shaefer: In a statistical model, I can predict, with a ton of precision, today’s poverty rate in a place in America based on a small set of factors from 100 to 200 years ago — including the level of segregation, the number of lynchings and the number of people enslaved. When you can sort of tell what’s happening in a place today based on things that happened hundreds of years ago, you really have to give up the notion that somebody growing up there today is somehow responsible for everything going on there.

In your research, did you look at how gender intersects with poverty and place?

Edin: Historically, in every place except Appalachia, women and children were working in the fields too. This is one of the reasons the school year was only five months long because the children were needed. Today, poverty and disadvantage has manifested in family structure, and so there has been a feminization of poverty: lots of single moms and kids living with a crumbling safety net. In some ways, the story for women and children is even worse now than it was when these great internal colonies ruled these regions.

Looking to the future, what kinds of solutions does your research point to? How can policymakers and community leaders help the most disadvantaged in the country?

Edin: Oftentimes, we funnel money through local government and local elites, and that’s a very risky thing to do in these places because it’s going to line the pockets of “the haves” and not trickle down to “the have nots.” We probably need more approaches that can be captured at the community level, like the child tax credit. Corruption is a huge problem, and we have to be vigorous and smart.

Shaefer: Policies that target people directly can do the most good, but there are also things that we have to confront. We need to elucidate what’s going on in a way that sort of breaks our assumptions. When people think of communities, they often think of them as entities that are working together with a set of goals or things they want to be about. But really much more, places have been a sort of fight or contestation between the people in control and everybody else. And this explains why a lot of the stuff we’ve tried to do as a country falls flat because we usually give money to community leaders — many who aren’t looking out for people in their communities. We need to do a lot more to try to train people who want to lead in their communities and help them break the cycle.

Edin: We also need a reinvigorated debate on separate but unequal education. We are as segregated today as we were prior to Brown v. Board of Education, and we’re not reckoning with it. It’s not in the public conversation, it’s like we’ve given up.

Shaefer: I think there’s also a strong case to be made for place-based reparations in this book. I think the citizens of each of these deeply disadvantaged places have a case to be made there.

Edin: Communities also need spaces where people can actually come together and form social bonds to prevent something like the opioid crisis. The diagnosis people in Central Appalachia gave us was that people were getting on drugs because there’s nothing to do, and we found really good evidence that that’s true. When the social infrastructure collapses, overdoses increase. So clearly, there’s this key recipe that the government is completely deaf to. It’s as life and death as physical infrastructure.