For the first 139 years of their existence, the federal courts were presided over exclusively by White men.

Article III judges, so named after the section in the Constitution outlining the creation of the Supreme Court and other courts with jurisdiction over the whole country, now encompass 870 seats in district, appellate and other courts. The judiciary’s size increased significantly over the 20th century, and with it came a slow shift in the demographics of nominees. The U.S. Customs Court, now known as the Court of International Trade, welcomed both the first woman federal judge as well as the first judge of color. President Calvin Coolidge nominated Genevieve Rose Cline, a White woman, in 1928. Irvin Mollison, a Black man, was nominated by President Harry S. Truman to the same court in 1945.

However, while the U.S. Customs Court had federal jurisdiction, it was technically a tribunal and didn’t have all the judicial power of an Article III court until 1956. The first woman to be appointed explicitly to an Article III court was Florence Allen, a White woman, who was nominated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and joined the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit in 1934. William Henry Hastie, a Black man, was the first person of color to be explicitly nominated to an Article III federal court, named by President Harry S. Truman in 1950.

President Joe Biden has nominated a historic number of women and people of color to the federal bench. According to Balls & Strikes, as of today, only four of the 83 judges he has nominated to Article III courts have been White men. Many of these nominees await confirmation from the Senate — including Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson, whose Senate confirmation hearings start today.

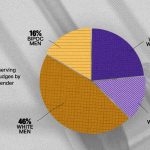

Even as the courts have grown more diverse, representation still lags. Right now, 71 percent of active Article III judges are White, compared with the 61 percent of Americans who identified themselves as White on the 2022 Census. Women make up just over a third of federal judges. Representation has tangible benefits — research has shown the benefits of increasing judicial race and gender diversity, including heightening trust within minority populations and addressing gender bias in courtrooms.

-

More from The 19th

- Ketanji Brown Jackson will be the first Black woman justice. Here’s how she will change the Supreme Court.

- Black women’s qualifications have long been questioned. Ketanji Brown Jackson’s allies were prepared.

- Four Black women became classmates, roommates and lifelong sisters. One of them is now a historic nominee for the Supreme Court.

The Federal Judicial Center collects biographical data for all Article III judges, and it makes clear that a recent influx of diverse nominees is still a drop in the bucket of the history of the federal courts. Five percent of active Article III judges today are Asian American or Pacific Islander, but throughout history only 1 percent of total judges have identified themselves as Asian American or Pacific Islander. Likewise, women make up 35 percent of active federal judges but only 13 percent of the historical total. Less than 2 percent of federal judges have been Black women. And this analysis focuses on only race and gender — there are few LGBTQ+ and disabled judges, for example. Additionally, many courts are not representative of the specific geographic populations within their jurisdiction.

One way to analyze the diversity of the federal bench is through the lens of descriptive representation, which looks to replicate population demographics within a representative group — so if 61 percent of Americans identify as White, then 61 percent of the federal judiciary should be White. But this approach doesn’t take into account time. Visualizing the demographics of federal judges by their first year of service on Article III courts shows how long White men exclusively ran America’s justice system. Take a look at the chart below to get a sense of just how long — and prepare to scroll for a while.