Mia Gingerich needed October 11. It might have seemed like an arbitrary deadline, but to Gingerich it was a way to honor her community — something formal to keep her accountable.

“I knew I couldn’t go through that day and not go through with what I had committed myself to do,” the Washington, D.C., resident said.

That date was National Coming Out Day 2020, an observance started by two activists in 1988 to celebrate queer identities and emphasize the power of LGBTQ+ visibility as politically transformative.

She wrote a Facebook post. “Today I would like to share a part of myself with those who do not already know,” it started. “The fear of sharing this is not easily managed, no more than the discomfort and sorrow of not sharing it would be, and so I will just say it.”

She was transgender, she told them. She changed her profile photo and updated her name, a terrifying and freeing feeling, she said. Most everyone who really mattered to Gingerich already knew she was trans. It was the old high school friends, and the distant relatives she never kept up with — the people peripherally in her life through Facebook — who needed to be informed. They overwhelmed her with acceptance and joy.

Gingerich is among millions of LGBTQ+ Americans who have participated in National Coming Out Day (NCOD). The observance is celebrated every October 11 by major LGBTQ+ rights groups, with social media posts, stories and in-person events.

“It is especially important during our current climate of LGBTQ+ issues as anti-LGBTQ lawmakers continue to add fuel to the anti-LGBTQ forest fire, which is resulting in stress among not only LGBTQ+ adults but LGBTQ+ youth as well, who already have an increased risk of suicidal behavior around their gender and/or sexualities,” Serena Sonoma, communications coordinator at the LGBTQ+ media advocacy organization GLAAD, wrote in an email to The 19th.

But as queer people gained the right to marry and increasing protections from discrimination, the day is increasingly fraught. Some resent the concept of “coming out” at all, saying that over-normalizes heterosexuality. Others find the day to be an agonizing exercise for those unable to be out as LGBTQ+.

Still, for many, the day holds deep personal and political importance. And its history would preview painful battles that LGBTQ+ people would continue to confront.

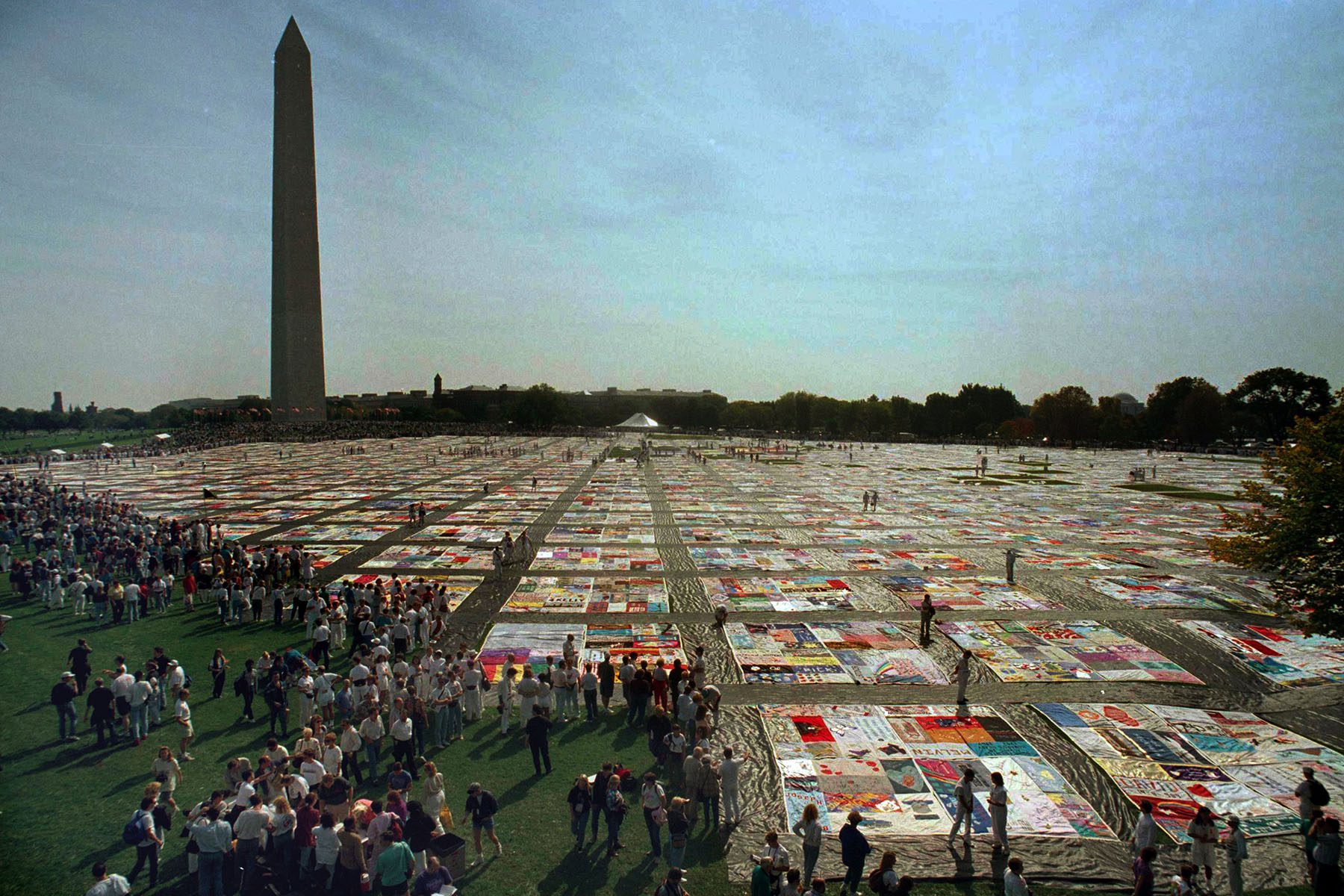

NCOD can trace its roots back to October 11, 1987, the date of the March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. The march, held between October 8-13, was the second queer march on the Capitol. This one aimed to draw attention to the federal government’s inaction in confronting the AIDS crisis and the Supreme Court’s 1986 ruling upholding Georgia’s anti-gay sodomy law. Protesters flooded Washington, D.C., over those five days and demanded legal recognition for gay and lesbian couples, funding for AIDS research, the abolition of sodomy laws and an end to the U.S. support of South African apartheid.

The march marked the unveiling of the AIDS memorial quilt, a massive patchwork honoring those lost to the virus, and at the time an unprecedented show of support for gay rights: More than half a million people showed up to demand their rights that fall.

Two activists— Rob Eichberg and Jean O’Leary — recognized the power of that momentum.

Eric Marcus, founder and host of the Making Gay History podcast, said the two had absorbed marketing best practices from others in the movement like Frank Kameny, who co-founded the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay rights organizations, and led some of the first LGBTQ+ rights protests in the nation.

“They figured out how to create something that was of benefit to gay and lesbian people in terms of their lives, and also had the potential to benefit the movement by creating visibility,” Marcus said.

So in 1988, on the one year anniversary, they organized the first National Coming Out Day, which quickly gained national prominence.

Getting to that moment of promoting visibility for the broad queer community in 1988 was not easy. O’Leary got her start in 1971, organizing with the Gay Activists Alliance, where she found that lesbians were being barred from leadership.

“The men actually treated women like surrogate mothers, lovers, sisters,” O’Leary told Marcus in a 1989 interview that later aired on his podcast. “The woman’s role should be respected.”

Appalled, she formed Lesbian Feminist Liberation in 1973. But that group would nearly fracture the movement for queer liberation when it decided to bar “drag queens,” the only terminology used at the time for transgender women, in Pride.

“In those days, it was like, well, here’s a man dressing up as a woman and wearing all the things that we’re trying to break free of,” O’Leary told Marcus.

That year, at the conclusion of Pride, trans activist Sylvia Rivera took the stage and blasted the exclusion in a now famous speech.

“You all tell me, go and hide my tail between my legs,” she said. “I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment. For gay liberation and you all treat me this way?”

At the time, O’Leary worried that “drag queens” were making a mockery of women. But as she got older, as she got to know trans people, her view changed.

“How could I work to exclude transvestites and at the same time criticize the feminists who were doing their best back in those days to exclude lesbians?” she asked Marcus in 1989.

By the 1980s, the queer rights movement had shifted, and so had O’Leary’s activism. According to O’Leary biographer Linda Rapp, the disagreement over trans inclusion that fractured Lesbian Feminist Liberation and other gay rights activists eventually healed, with lesbians and gay men coming together over trans rights. O’Leary reunited with friend Bruce Voeller at the Gay Activists Alliance, and the two folded their organizations into the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, which today is the National LGBTQ Task Force, a powerhouse queer political organizing machine.

In 1988, O’Leary joined forces with the psychologist and activist Rob Eichberg. Eichberg had done gay and lesbian organizing himself and created a personal development workshop called “The Experience,” which encouraged people to come out to friends and family.

O’Leary and Eichberg decided to organize the day with a dual purpose in mind: They wanted to give people the safety of a community experience to be themselves, but they also saw the political power in coming out. Like the gay rights leader Harvey Milk, they believed that straight people would find it easier to discriminate against a faceless community. Shunning your own gay brother, sister, daughter or friend would prove harder. If people came out, the country would be forced to confront the movement.

“Virtually everyone in America knows someone who’s gay at this point — you really have to work hard not to know someone gay,” Marcus said.

Marcus feels that today, the day is more necessary for trans and nonbinary youth, for people of more marginalized genders — the ones that O’Leary herself needed help understanding.

And that, advocates say, is perhaps why it still resonates even though the realities facing so many gay people have changed since the 1980s.

“Just as conversations around LGBTQ+ awareness evolve, so do events that surround it,” Sonoma said. “The more we are able to share our stories and highlight our own experiences, the more it urges others to stand in their own truths as well, I believe in this way Coming Out Day has evolved.”

For Gingerich, the last year of being out has changed everything. She’s looking forward to observing outside the metaphorical closet.

“I guess I get to be the supportive individual now, the person who encourages people,” she said.