In December 2020, class-action lawyer Tom Girardi was sued by a class of his former defendants from the 2018 Lion Air flight crash in Indonesia. Tom Girardi, they said, defrauded them and funneled cash from settlements to his personal accounts.

Some of that cash, the lawsuits say, went to his wife, Erika Girardi, one of the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills and a chart-topping dance pop performer who went on to write a New York Times-bestselling memoir and star on Broadway in the long-running musical “Chicago.”

(Both Girardis will be referred to by their first names in this article for clarity.)

When the Bravo show’s 11th season opened, the two seemed happily married: In the season premiere, Erika told castmates about how COVID quarantine had made for a much-needed time for reconnection between a couple who had started to grow distant. While she also mentioned how hard being stripped of her ability to work was during that time and how it was a particularly dark period in her personal life, the woman famous for singing the words “It’s expensive to be me” — and showing off her homes and private planes and collection of cars and 24/7 on-call glam squad — nevertheless made it seem that the status quo of her life, socially and economically, was plenty stable.

But then Erika revealed she had filed for divorce, and fellow cast members learned of the lawsuits, which included a bankruptcy suit that also named Erika as a defendant. While both Girardis have repeatedly asserted their innocence, the core questions of the season became: What did Erika know? When did she know it? How could she not have known what was happening with her husband’s — and her own — finances, while having no access to assets of her own?

By her own account, Erika Girardi’s marriage held grave power imbalances — the couple met when she was 27 and he was 60, when she was a cocktail waitress and single mother, and he was an established high-profile attorney. Bravo’s Andy Cohen — an executive producer on the “Real Housewives” franchise — pointed out the post-season reunion special that Erika has her own income, with a “Housewives” salary that is comfortable by any stretch of the imagination.

The Girardis’ situation continues to change. Tom, 82, has been placed under a conservatorship held by his brother and been diagnosed with dementia and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease since the initial fraud suit was filed.

Erika said that throughout her marriage, all of her paychecks were turned over directly to her husband. It has only been since filing for divorce has her income been her own.

Shows like the “Real Housewives” franchise have made it clear how much love — and hate — there is for gratuitous displays of wealth. The shows’ stars often only reinforce feelings many people may already have about gender, income inequality and the public notion of “success” and who has access to these things in America. But experts also point out that stereotypes about gender and money can have consequences for some survivors of domestic abuse, including economic abuse: Someone who appears independent and earns their own money can still be controlled by a partner.

The 19th spoke to experts on how wealth, control and abuse can intersect in an intimate relationship. Their comments were not on the Girardis’ individual situation, which is still working its way through the legal system. Here’s what they said:

Economic coercion is a form of intimate partner abuse

America is still waking up to the concept of economic abuse as a form of intimate partner violence, said Laura Johnson, a professor of social work at Temple University who is an expert on gender-based intimate partner violence (IPV). Even among the general population — those whose relationships would not be described as abusive or violent — 15 percent of all women experience some form of financial coercion, Johnson said, and almost all victims who experience intimate partner violence also experience economic abuse.

Rachel Voth Schrag is a professor of social work at the University of Texas who studies intimate partner violence prevention and improving access to economic empowerment resources. She explained to The 19th that economic abuse tends to fall into three main categories of behavior. The first is known as economic control, or one partner limiting access to a couple’s bank accounts and not allowing one partner to be involved in the household financial decision making. The second is what’s known as economic exploitation — forcing a partner to deposit their paycheck into a partner’s account, labor trafficking a partner, or exploiting jointly held assets or financial property. And the third is often called work or school sabotage: limiting or prohibiting someone from work they would otherwise be capable of doing and preventing them from training opportunities that would allow them to join the workforce.

It can happen to anybody

People who experience housing or food insecurity are more likely to experience forms of physical intimate partner violence, as are people of color. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 9 men experience severe intimate partner violence in the United States. Anywhere between 30 and 50 percent of all trans people will experience some form of domestic violence in their lifetimes.

And while people with more economic resources may have fewer barriers to leaving an abusive situation, they can still be victims.

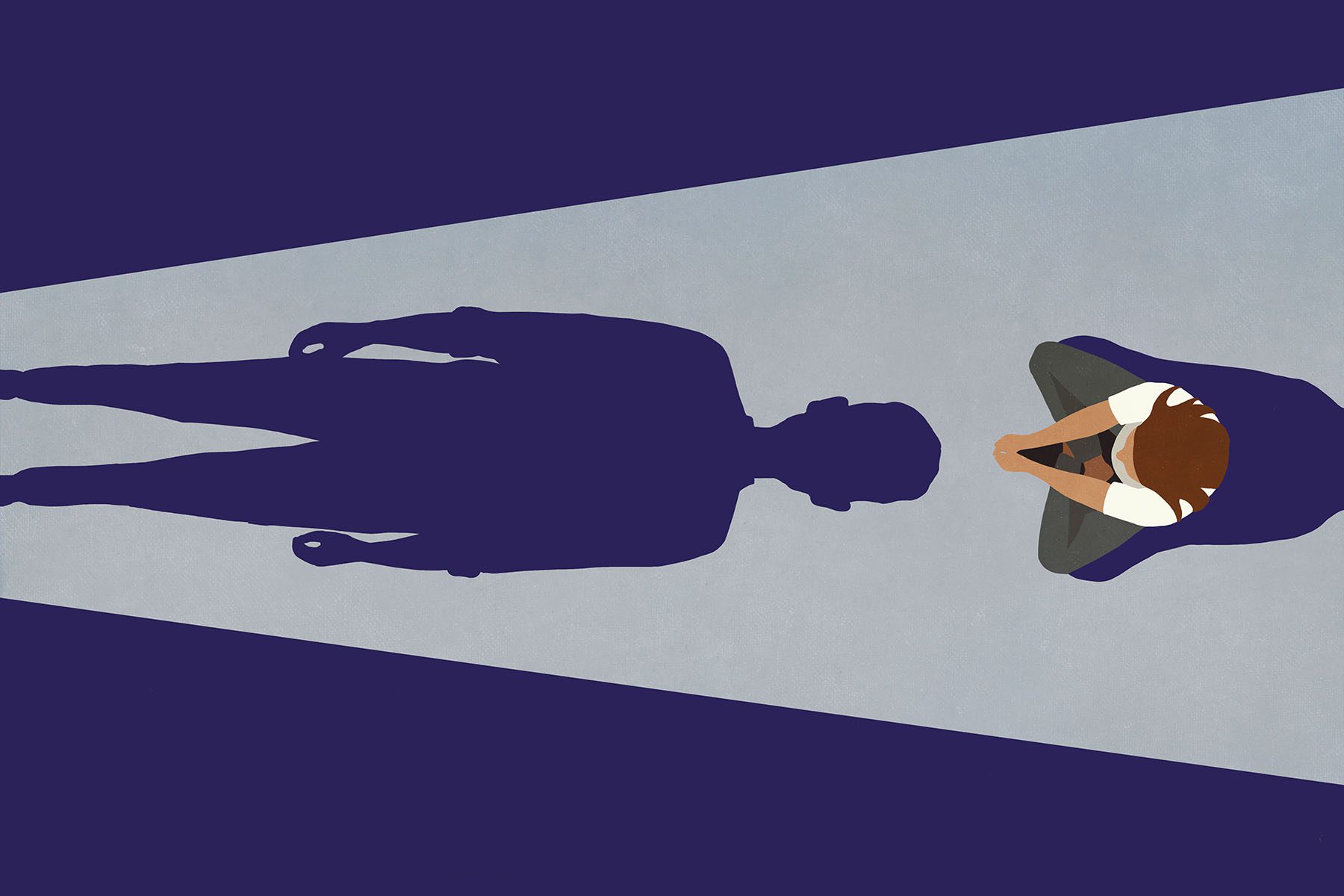

“There is definitely a perception that survivors have to look a certain way and that abusers have to look a certain way, and that’s certainly not the case,” Johnson said. “It doesn’t matter how educated someone is, how much money they have, where they factor into the community, or their employment status. What you see on the outside has nothing to do with the context of their home life.”

Johnson said that further complicating situations of economic abuse is the lack of financial literacy education in the United States and how this intersects with gender in relationships. Long-standing stereotypes have been inherited by many heterosexual couples.

“There is this idea that the man is the primary breadwinner and manages money in the household. There are these kinds of gendered notions of financial management in families, but no one person in a couple is actually receiving the financial education to understand the nuances of things like how to get out of debt or how to increase credit,” she said.

This means many women find themselves in a financial situation that they did not intend to be in, led by a male partner they believed should have been capable of managing these things on his own.

“We are so socialized as a culture to think, ‘Oh it’s normal for the man to have access to the money.’ Even the expression ‘boys will be boys’ — we think these behaviors are all just misunderstandings, and if survivors are questioning things, they must be misunderstanding them,” Johnson said.

It isn’t unusual to see a partner who is a survivor of any form of intimate partner violence — including economic abuse — present as someone “strong” and “tough” for exactly these reasons, Voth Schrag said. Survivors of abuse of all kinds “are strong and use all that resilience to deal with the situation that they are in. We know survivors do a thousand little things a day in an effort to keep themselves safe.”

Affluent women are controlled in particular ways

Among affluent people, economic abuse often manifests as what’s known as “functional poverty,” said Megan Haselschwerdt, the director of the Family Violence Across the Lifespan research team at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. Though on paper women who have a high status and a high-powered partner appear to be of high status themselves, and have access to significant financial resources, in reality they are held to an intense budget set by their husbands and have no access to money on their own.

“They might drive a fancy car and their kids might go to fancy private schools to uphold the image of power for the family, but they have no access” to any family resources independently, Haselschwerdt said. These women are often PTA presidents, social tastemakers and philanthropic heavy hitters — exactly because “their husbands know that if they isolate their wives at home, that would be a red flag, something inconsistent with their community norms.” So the women in these relationships are social and appear to live large, despite having absolutely no financial independence.

Abusive partners may use threats and coercion to keep them from their resources. “There’s a real loss of autonomy that comes with that,” Voth Schrag said.

Sometimes abusers threaten their partners with outing their immigration status, ability to see their children, or revealing otherwise private things about their sexuality or sexual orientation, but in high-profile relationships, a main threat utilized — whether verbalized or not — is shame.

“There is this perception of your relationship and what the world sees of you, as someone who has this great life. In actuality if that is not the case, it can be shameful and embarrassing,” said Johnson.

People often don’t believe it’s possible

It’s hard for people to believe that someone with significant means or who is known for their philanthropy could be an abuser, experts say.

“You think, ‘This person is such a great member of the community! They couldn’t be doing this!’ But how a person engages with their community is totally different from how they engage with their partner,” Johnson said. “With partners, you have this larger context of control at play. You’re not trying to control a community, which is why being able to control a partner is so easy to hide.”

Haselschwerdt stressed that cultural stereotypes about affluent people go hand-in-hand with misperceptions about economic abuse as a form of intimate partner violence. “We have this assumption about how a survivor of intimate partner violence is supposed to look. We think there has to be physical violence — black eyes and bruises.” Haselschwerdt’s research has shown that when affluent women seek out help after experiencing IPV, they are less likely to receive it.

“We all know that money doesn’t buy happiness, but we expect that it should buy you some level of happiness — or at least protect you from some level of societal ill like domestic violence,” she said. “We think that this just doesn’t happen in affluent communities.”

Affluent communities don’t want domestic violence shelters and other resources in their communities, Haselschwedt said. They value privacy and status so keep out resources that could help.

Perceptions about who victims are, and how abuse works, mean some claims are met with skepticism.

“Each situation [of economic abuse] is far too complex for folks on the outside to have a full accounting for it,” said Voth Schrag. “The survivor is the only one who knows what’s going on in a relationship.”