The nation’s first COVID-19 vaccines should be given to health care personnel and people who live in long-term care facilities, a major federal advisory committee voted Tuesday.

The recommendation, which passed 13-1 in a vote by the government’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), could have major ramifications for women, who make up 75 percent of the nation’s health care workers.

But the implications for pregnant health workers are less clear. The ACIP acknowledged that those workers are at heightened risk of COVID-19 mortality, but also noted that none of the initial vaccine products have been tested in pregnant people specifically — a decision that has sparked criticism from some health care experts. With that caveat, the committee did not take a stance on when pregnant or breastfeeding health care workers should get immunized in that first round.

That means their inclusion in any early vaccine rollout remains an open question, and will likely vary amongst individual states and health care systems.

Meanwhile, a major medical society the same day put out a statement recommending pregnant health care workers be offered vaccines as a high-priority group alongside their non-pregnant colleagues.

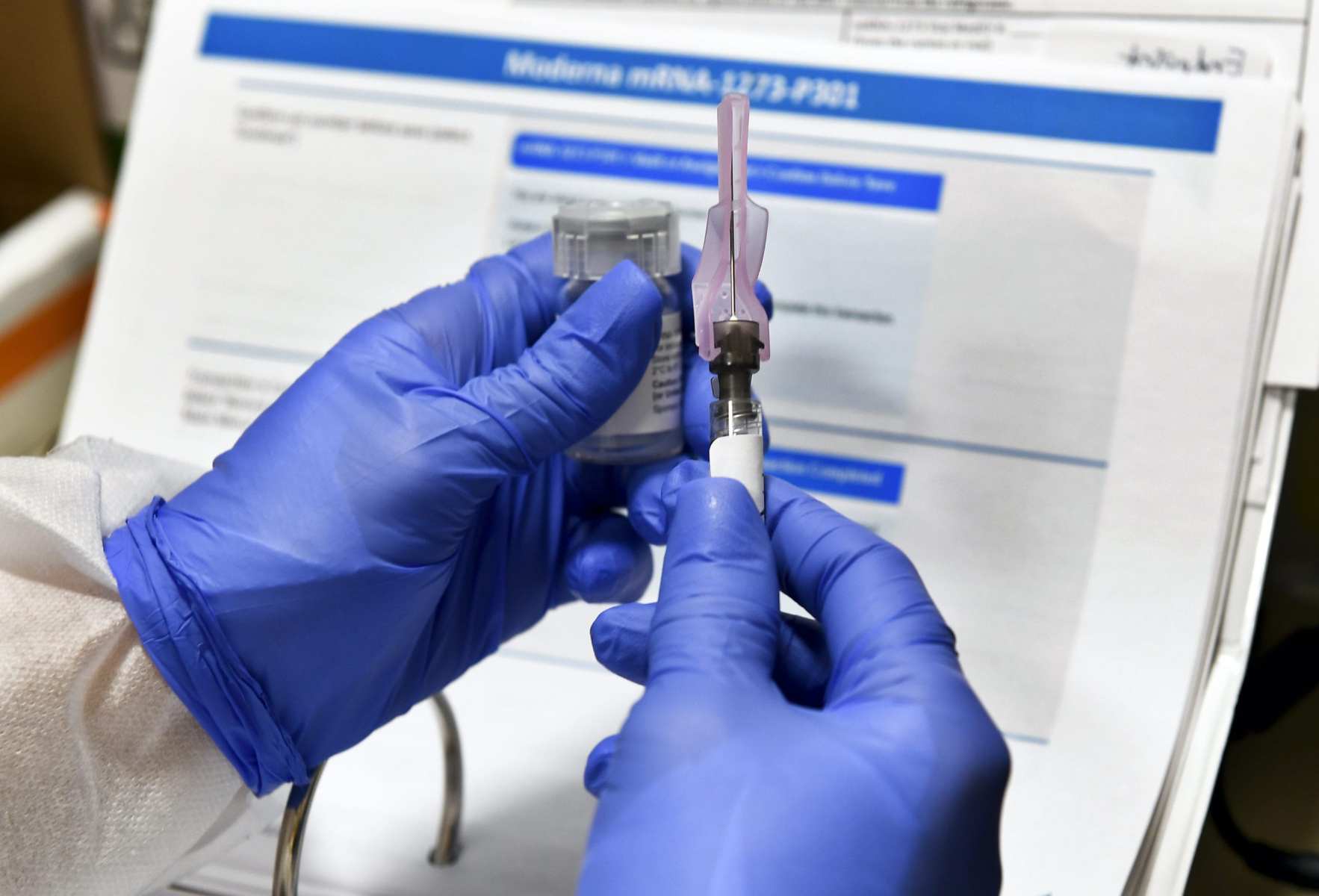

If accepted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the ACIP recommendation would likely shape how states decide to distribute the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines. Those vaccines could become available this month, pending applications by pharma companies Pfizer and Moderna to the Food & Drug Administration for federal “emergency use authorization” for their products. If the FDA grants those requests, the vaccines could be administered before the government sees the full data to formally approve them.

Pfizer and Moderna are expected to have enough COVID-19 vaccines available by the end of the year to immunize about 20 million Americans. The nation has about 21 million health care workers and 3 million people living in long-term care. The supply limits mean not all people in each group would necessarily get vaccinated immediately, said Sara Oliver, a CDC physician who spoke at the meeting.

The ACIP estimates that about 330,000 members of the health care workforce will be pregnant or recently postpartum when initial vaccines are being distributed. But the committee said it would wait until more information comes from the FDA — which has been tasked with authorizing new vaccines for use — as well as for full vaccine data from both Pfizer and Moderna’s late stage clinical trials before deciding how to approach these workers.

“We anticipate further guidance around the use of COVID vaccines in pregnant or breast-feeding Phase 1 populations,” Oliver said at the meeting.

Some medical groups that focus on pregnancy have argued that pregnant health care workers should be given the option of taking the vaccine when it is given to their colleagues.

In a statement released Tuesday, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), a physician group that focuses on caring for people with high-risk pregnancies, argued that, if health care workers are the first to be eligible for vaccines, pregnant workers should receive the chance to be included in that group.

SMFM also says doctors should message that the underlying mechanism behind both Moderna and Pfizer’s vaccine — messenger RNA, which induces a cellular immune response against COVID-19 – theoretically bears little risk to fetuses.

In an October public comment addressed to the ACIP, the American College for Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which represents more than 60,000 health care professionals, made a similar argument.

“It is critical that a vaccine allocation plan explicitly outline that pregnant and lactating women who otherwise fit the criteria for inclusion in a high-priority population can be vaccinated alongside their non-pregnant peers,” wrote Christopher Zahn, the organization’s vice president of practice activities.

These kinds of recommendations should bear weight with pregnant health care workers in particular, said Ruth Faden, a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University who focuses on immunizations for pregnant people.

“From the standpoint of pregnant women, it’s good to know there is an authoritative group of experts who are concerned with the health of women and babies who think that, on balance, it’s all right to take this vaccine,” Faden said. “I would imagine some pregnant women who are health workers who are in roles where they see themselves at elevated risk of becoming infected look at this picture and say, I’m being offered the vaccine, and I’m going to take it.”

But unless the ACIP affirmatively recommends that pregnant health care workers be included in the high-priority category, individual states — and, more probably, individual health care systems — will likely decide whether the vaccine is in fact offered to these people.

An FDA committee will review clinical trial data from Pfizer next week, and Moderna the following week. Following those reviews, the ACIP and CDC will make subsequent recommendations about how to disperse the vaccines.

Because they will include more vaccine data, those meetings could provide clarity about how pregnant health care workers should be treated in the initial vaccine rollout, said Sonja Rasmussen, a 20-year CDC veteran and professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at the University of Florida.

“Once we see the data on effectiveness, side effects, and safety, I think pregnant women should be allowed to make an informed decision, in discussion with their health care provider, after considering the risks and benefits associated with the vaccine for their personal situation,” Rasmussen said.