In Florida, transgender people can no longer update their driver’s license with their correct gender, according to a memo shared by the Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles (FLHSMV) in January. Although the rule does not apply to Floridians who have already updated their licenses, and should not affect first-time applicants, it still puts trans people at risk of discrimination in everyday interactions.

Multiple Democrats in Congress, as well as the LGBTQ+ advocacy group Equality Florida and several legal experts, believe that the highway safety department rule likely takes Florida out of compliance with the Real ID Act — a federal law that will be enforced in 2025. But there’s currently no sign that the federal government agrees.

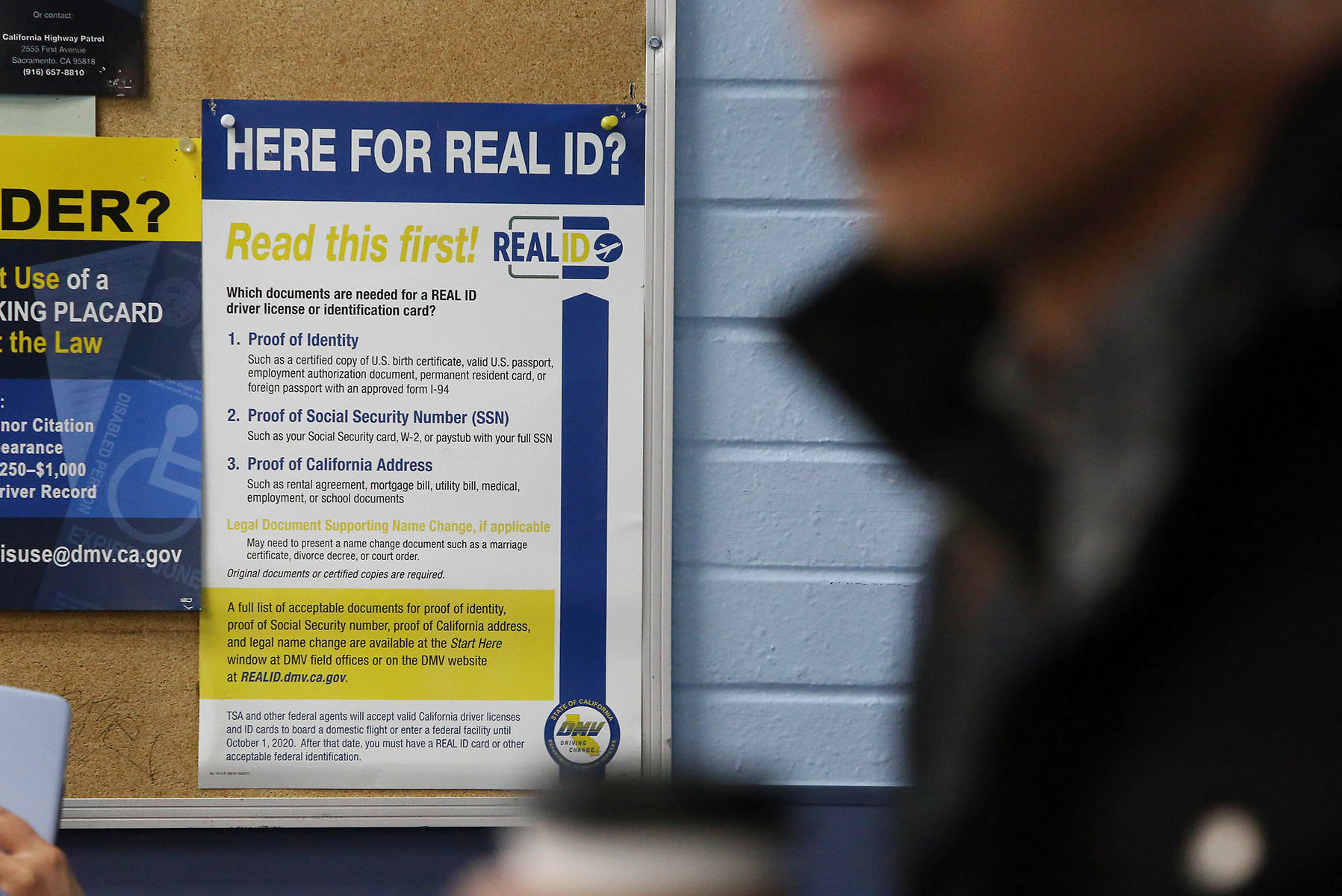

The Real ID Act, passed in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, aims to make identity documents “consistent and secure” by setting shared security standards for licenses in all states. After May 2025, all state driver licenses will need to be Real ID compliant, and Americans will need a Real ID license to board domestic flights.

Among the requirements of the Real ID Act are that states include a person’s gender on each driver’s license.

The FLHSMV states that their new rule is in compliance with the Real ID Act. But the agency is defining gender as “biological sex,” which many states have tried to do in order to stop legally recognizing trans people in public life. That interpretation is not specified or sought in the Real ID Act.

“We do include gender on the credential as required by the Real ID Act,” FLHSMV communications director Molly Best said over email.

Florida’s policy ignores the complicated reality on the ground, said Cathryn Oakley, senior director of legal policy at the Human Rights Campaign. She expects that it will be a challenge for Florida to issue Real IDs under the state’s new policy.

Florida has been issuing Real IDs since 2010 — and receiving one requires bringing documentation to the DMV such as a passport and a Social Security card. These documents, beholden to federal rules that allow gender marker changes, may reflect a gender identity that Florida has now elected to ignore when it issues replacement licenses.

“If Florida is insisting on only giving out identification that is misgendering someone, those documents that are reflecting their correct gender are going to be in conflict and will hold up the process,” Oakley said. “They’re going to be relying on documents that have a different gender identity on them, potentially.”

In February, Rep. Maxwell Frost and seven other Florida Democrats asked Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas to take action in response to Florida’s new policy. Frost and his colleagues pointed out that the directive equates gender to mean sex — and said that such a provision would create confusion and inconsistency that would hamper Americans’ ability to travel.

“Forcing Floridians to carry driver licenses that may not correspond to their gender is in direct conflict with the stated purpose of the Real ID Act,” Frost and his colleagues wrote in their letter.

The policy will lead to potentially dangerous situations where an individual’s Florida driver’s license and federal documents, like a passport, list two different genders, the representatives argued — which could lead to unnecessary detentions and unlawful stops. They urged the agency to pursue rulemaking under the Real ID Act to require that one’s gender or sex marker on a driver’s license match their gender on federal identification documents.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to requests for comment on Florida’s policy or whether the agency plans to take action. Frost’s office also did not respond.

Equating gender to “biological sex,” or sex assigned at birth, has long been a staple of anti-trans legislation across the country. Within the past two years, conservative lawmakers have used that logic to push more extreme policies that would exclude transgender people from updating driver’s licenses and accessing public restrooms.

Florida’s policy is defining gender differently than the federal government does — which is what likely puts it out of compliance with the Real ID Act.

“They’re not wrong, necessarily, in saying that they are collecting gender, because they are,” said Simone Chriss, attorney with the Southern Legal Counsel in Florida and director of the organization’s transgender rights initiative. The FLHSMV memo published in January uses the word gender, she said, but the problem is that the agency has redefined gender to mean sex assigned at birth — which is inconsistent with other identification documents, including passports and other federal documents.

“I think it’s likely that it is violating the Real ID Act, but I don’t know what elements are required to prove that,” she said. Outside of the Biden administration telling Florida that they’re out of compliance, she’s not sure what else could be done to hold the state accountable.

Multiple Biden administration officials agreed on background that challenging the policy in court would be a promising course of action. None, however, indicated that the administration had plans to do so.

When asked, Department of Justice spokesperson Aryele Bradford replied, “We are declining comment.” The White House did not respond to multiple requests to comment on this story.

Oakley believes that the Florida policy and the federal government’s requirements under Real ID are on a collision course — and that at some point, someone in Florida will be denied a Real ID license that accurately reflects their gender identity.

“At that time, I would expect that litigation might be an excellent option and an enforcement action by the administration might be necessary at that point as well,” she said. “But as far as I know, that situation has not yet occurred.”

President Biden, who has achieved a number of substantial policies to undo former President Trump’s anti-LGBTQ+ agenda, has also overseen a country that has grown increasingly hostile to transgender Americans, many of whom have begged him to use his platform and power to combat violence against them.

Before taking office, he vowed to pass sweeping LGBTQ+ anti discrimination protections in the form of the Equality Act, first introduced to Congress 50 years ago. He re-upped that call during his 2024 State of the Union address and reaffirmed support for transgender Americans.

Sasha Buchert, director of the nonbinary and transgender rights project at Lambda Legal, said her organization appreciates that inclusion in the president’s address and added: “It remains imperative that this administration continue to translate those values into executive action.”

Carlos Guillermo Smith, a former state lawmaker who is now senior policy advisor to Equality Florida, said the organization supports Rep. Frost’s effort to ask DHS to issue rules requiring states to be in alignment with federal policy.

Florida’s rule, he said, “blocks transgender Floridians from obtaining accurate state-issued identification, so that it’s obviously denying their legal existence, but it also is out of compliance with the mission and spirit of the REAL ID Act, which is to make identity documents more consistent and secure.”

However, not all LGBTQ+ advocacy groups agree on whether Florida’s new license policy takes the state out of compliance with the Real ID Act — and if the Biden administration should take action on it.

“Whether termed as ‘sex’ or ‘gender’ or otherwise, the Real ID Act grants states wide discretion to establish their own guidelines for defining gender,” said Olivia Hunt, policy director of the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE), in a statement.

If the DHS were to require states to define gender in a specific way under the Real ID Act — a lengthy rulemaking process that would carry on beyond the necessary congressional deadline — that rule may have unintended consequences, she said.

Such a rule would potentially leave transgender people in non-compliant states unable to use their state IDs for airport travel and access to federal buildings after the May 2025 deadline, Hunt said. The NCTE advises trans people in states that don’t permit gender marker corrections on state IDs to obtain a passport instead, she said, since a passport is “a REAL-ID-compliant document.”

Florida’s policy may also be at odds with the Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County, the work discrimination case in which the court found gender identity to be a protected class of sex. As a result of Bostock, people in all states can seek legal recourse for employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

In Bostock, the Supreme Court found that discrimination against trans people is inherently sex discrimination, Chriss said — and refusing to allow transgender people to amend their gender marker is an example of that discrimination. Such a policy punishes people for failing to comply with sex stereotypes, she said.

“This draconian definition of sex that the state of Florida and others have come up with is at odds with Bostock, in that it literally redefines sex in a way that excludes transgender people and nonbinary people and intersex people,” she said.

Oakley sees a different problem. To her, the Bostock decision is not binding on the state of Florida in terms of making a determination about gender markers on driver’s licenses — but Florida appears to have differing interpretations of sex across various state laws. The state explicitly interprets existing protections against discrimination based on sex to include both sexual orientation and gender identity, according to the Movement Advancement Project, which tracks LGBTQ+ policy.

“The logic of ‘What do we think sex should be defined as, or is defined as?’ — those two things are in conflict here,” she said.

The Southern Legal Counsel in Florida is currently exploring options for a lawsuit against Florida’s driver’s license policy, Chriss said.

“It’s safe to say we will be challenging it. It’s just a matter of when and on what basis,” she said.